Syster Systems

On the urgencies and potential of feminist hacker initiatives

Prologue

Being a Western millennial woman, I was raised together with my internet. Every day, on my numerous open tabs, I encounter news, advertisements, gossips and chronicles; vibrant mosaics of information appear on my devices. Assisted by the magic technologies that come to my hand, I do things more quickly and accurately. One might think these growing capabilities would lead to autonomy. Here, however, one encounters a paradox, as consuming these ever-developing technologies raises instead the issue of dependence. We depend on those who develop technology, on their business plans, or their contributions to social value. And we change along with technology (Padilla, 2017). It is thus critical to keep questioning which technological horizons are relevant for us, and how we are building them.

In my early adult years, influenced by European autonomous movements, I became involved in Greek political and activist communities. Their aim was mainly to point out social exclusions in terms of class, race, ethnicity and gender, and to critique the imbalances of current power structures. For such groups, exploring ways to become more technologically sovereign is still a constant struggle. Their critique of contemporary technology production makes them sceptical towards new technologies and their use for surveillance, control, and oppression by power institutions. While I agree with this tendency, I have noticed a gap between theory and practice inside these communities. How can we overcome the binary notion of producers and consumers, let alone imagine autonomy, without having basic technological literacy and skills?

Willing to practically engage with technology, I started looking for places that could be starting points for amateurs like me. Some of my male friends who were software developers and open-technology enthusiasts suggested I should attend a hackerspace. However, I was discouraged from joining due to shared experiences from my close female friends who have already attempted to enter hacker communities. They described these as male-dominated, competitive, massively technocentric, and hard to fit in as a woman. While I was still searching for spaces to acquire technical skills at my own pace, I received an invitation to an international event which combined technology with feminism. Participating in this gathering inspired me to further study the work of feminist hackers.

In this essay, I will examine the context of technological environments that lack diversity and inclusion, as well as the practices of feminist communities that respond to this phenomenon. First, I will explore how the origins of hacker culture have contributed to the creation of gender-based social exclusions. Then, I will narrate how sexism and misogyny reproduce in the geekdom, highlighting the importance of addressing this phenomenon. Finally, I will present the practices of feminist hacker communities, emphasising the value of supporting their work. Not only because they create safe spaces for excluded individuals to gain agency with technology, but also because, as Christina Dunbar-Hester, ethnographer and researcher of the politics of technology, puts it, they redefine who counts as a hacker, and what counts as hacking (Dunbar-Hester, 2020). Their efforts to encourage collective knowledge production and Do-It-Together practices in inclusive and diverse environments envisage a technological future where I could see myself fitting in.

Chapter 1 - A boys-only club

Over the last three decades, the explosive growth of the information technology industry has lead to an increased interest in this industry. Mass media, national governments, and college administrators began advertising employment in computing as the most promising career path (Dunbar-Hester, 2020). Successful tech entrepreneurs and programmers like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Steve Jobs became our new role models; all of them white, upper-class men. Steve Henn, host of the podcast When Women Stopped Coding, narrates that plenty of early computer ads from the ’80s were full of men and boys. Nobody can be sure why they became a better target market for computers, but this idea fed on itself; that “computers are toys, that boys use to do boy things” (Henn, 2014). In parallel, the rise of male geek character representation in pop culture, for example in the TV sitcom The Big Bang Theory, legitimises the geek as a new form of masculine identity (Morgan, 2014).

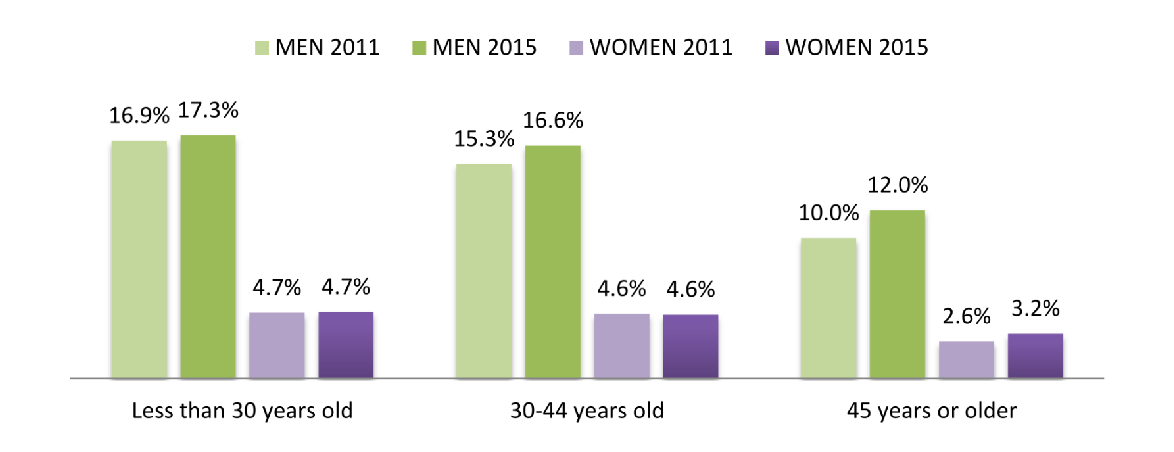

In 1991, Dr Ellen Spertus inquired into the reasons why there were so few female computer scientists. In her study, she reported that, at the time, only 13% of PhDs in computer science went to women, and only 7.8% of computer science professors were female (Spertus, 1991). In 2020, journalists, researchers, and politicians are still asking the same question. A recent European Commission study reports a growing gender gap in the digital sector. Women’s participation in ICT studies is four times less than that of men, a decrease from 2011. Also, the rate of men working in the field is 3.1 times greater than the share of women (European Commission, 2018).

Fig. 1: Labour market distribution of individuals in digital jobs by age and gender

Why are women avoiding tech-based environments? How did the association of hacking competence with masculinity become a norm? Sociologist Tim Jordan argues that hacking inherited the gender biases of computer science, in numbers as well as in attitudes. A cultivated culture of male dominance and even exaggerated misogyny pushed away most female developers (Jordan, 2016). Historical narratives about the origin of hacking may indicate how the culture of hackers grew to exclude people not fitting their repetitive identity pattern.

Hacker, a title of honour

Steven Levy, in his book Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, describes the birth of computer hacking at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the ’60s. MIT’s famous Radiation Laboratory contributed to the development of advanced military systems after World War II. Digital Equipment Corporation donated a large-scale computer to the Lab, which had previously been used for military purposes. This computer, among others that followed, became a central point around which the first groups of obsessed tech tinkerers and programmers gathered (Levy 1984). The protagonists of this story – young, curious, well-educated white men – would gradually form a community characterised by a particular culture. Hacking became a self-conscious and widely noticed practice, with its own intellectual pursuit and values (Jordan, 2016).

In public perception, a hacker is usually someone who breaches internet security systems, although this is not always true. The epic battle over who is entitled to call themselves hackers is under constant debate. Richard Stallman, programmer and founder of the Free Software Foundation, in his many speeches and writings, presents himself as the rightful carrier of the proper definition of hacking:

Hacking, as a general concept, is an attitude towards life. What’s fun for you? If finding playful clever ways that were thought impossible is fun then you’re a hacker …. journalists found about hackers around 1981, misunderstood them, and they thought hacking was breaking security. That’s not generally true: first of all, there are many ways of hacking that have nothing to do with security, and second, breaking security is not necessarily hacking. It’s only hacking if you’re being playfully clever about it (Stallman, 2012).

In his attempt to emphasise the playful nature of hacking, as opposed to its malicious version, Stallman’s above definition only tells half the story. Although some journalists have misunderstood hackers, others have tried to present them as mythical figures and heroes of the digital revolution:

Those magnificent men with their flying machines, scouting a leading edge of technology which has an odd softness to it; outlaw country, where rules are not decree or routine so much as the starker demands of what’s possible (Brand, 1972).

This is what Stewart Brand wrote about hackers in 1972. Stewart Brand is best known as the publisher of the Whole Earth Catalog, a famous magazine that became a bible for a big part of the American counterculture in the ’60s and ’70s. Specifically, for the role it played in promoting the back-to-the-land movement and communal life, and even adopting semi-religious systems from the exotic East (Turner, 2006). It is interesting to notice how this new-age spirituality went together with the glorification of what was described as an aethereal new technology.

Hacker ethics and aesthetics

Steven Levy found in hackers a “daring symbiosis between man and machine”, whose urge to learn, tinker and create technical beauty supersedes all other goals (Levy, 1984). He codified an overall “hacker ethic” in a list of tenets that promote a hands-on imperative, a dedication to information freedom, a mistrust of authority, a commitment to meritocracy, and the faith that computers can improve people’s lives. Many people, coming from different political and ideological backgrounds, find the tenets of hacker ethic appealing, probably because of the constant invocations of freedom. “Information wants to be free” (IWTBF) is one of the most common slogans used by hackers. This sentence is half of a famous quote by Stewart Brand, recorded at the first Hackers Conference in California, in 1984. In its original form, this aphorism could advocate for free and open information, but could also be an argument in favour of the benefits of proprietary information:

On the one hand information wants to be expensive, because it’s so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life. On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of getting it out is getting lower and lower all the time. So you have these two fighting against each other (Brand, 1984).

Fig. 2: Hackers conference, 1984

This statement reveals a paradox of the digital age. Information becomes subject to the law of supply and demand because of its role as a growing source of value. In parallel, the cost of preventing information to spread becomes bigger. The more information technology grows, the more value it produces. However, the more information technology there is, the easier it is for information to spread. Behind this abstract slogan (IWTBF), lies the notion of economic liberty.

Anthropologist Gabriella Coleman, whose work focuses on hacker culture and online activism, links hackers’ hyper-elevation of individualism and meritocracy to the long history of these terms in the liberal tradition (Coleman, 2012). Nevertheless, Coleman points out the difficulty of generalising about hacker politics, as they bring together faith in freedom of speech and information, values from traditional liberalism, a great deal of geekiness, and some scent of counterculturalism. They generally tend to avoid rigid political stances, embracing “political agnosticism” (Coleman, 2004). However, there are times when more radically political branches of hacking appear. Hacktivism is the fusion of hacking and activism or, in other words, hacking for a political cause. The tactics used by hacktivists vary, including electronic civil disobedience, online demonstrations against corporations, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks to freeze websites, cyber-attacks to gain information on political opponents, and more (Toupin, 2015).

Who fits in hackerspaces?

Hackerspaces are tech-oriented open spaces where people gather to hack, tinker with technology, experiment and socialise (Dunbar-Hester, 2020). Different kinds of hackerspaces, hacklabs, co-working spaces, media labs, fab labs, and more, exist in different contexts such as universities, start-up companies and non-profit organisations. According to Johannes Grenzfurthner and Frank A. Schneider, the first hackerspaces in Europe were part of the broader “autonomist” scene. They developed in the mid-’90s, among squat houses, alternative cafés and communes (Grenzfurthner & Schneider, 2009). Hackerspaces that followed and became widespread during the late ’00s gradually lost their prior political identity. They embraced more academic and liberal approaches, growing in the sphere of influence around the Chaos Computer Club (CCC), Europe’s largest association of hackers (Maxigas, 2012).

The operating principles of hackerspaces coincide with those of Free, Libre and Open-Source Software (FLOSS), encouraging everybody to share code, ideas, and the projects these produce. This approach is appealing to many people who are interested in open access to information, decentralised technologies, digital rights and more. Moreover, people who are new to hacking often choose hackerspaces as their entry point for technological projects. That being said, while the communities running these spaces should provide a safe and welcoming environment, they have been struggling with diversity and inclusivity for a long time.

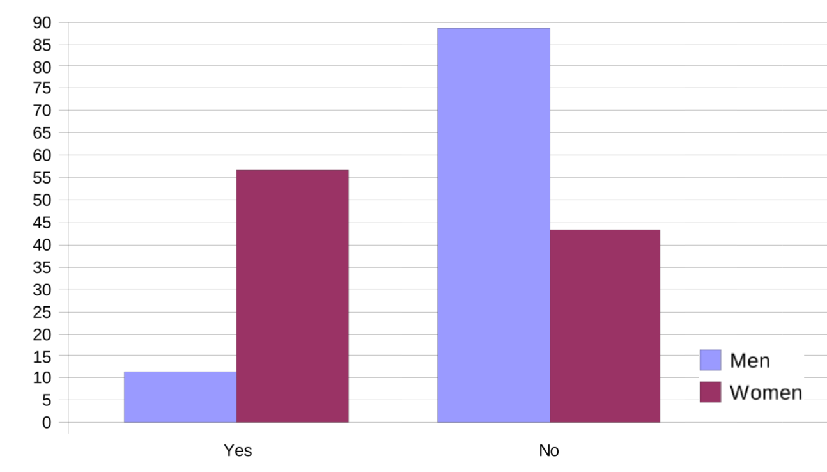

In 2006, a European policy report shed light on the severe diversity issues of open source communities and hackerspaces, which is even worse than in tech overall. At that time, less than 2% of FLOSS community members were female, compared with 28% working in academic computer science or proprietary software development. The study also revealed that, although most hackers see themselves as neither sexist nor hostile towards women, most female participants of the survey had observed or experienced discriminatory behaviour against themselves or other women in the general FLOSS community (Nafus et al., 2006). In 2017, a more recent survey from GitHub showed that gender imbalances in FLOSS remain profound. 95% of the respondents were men, only 3% were women, and 1% non-binary (GitHub, 2017).

Fig. 3: Survey respondents to the question: Regarding your collaboration with others during your FLOSS activities, have you ever observed or experienced discriminatory behaviour against women?

In addition to these reports, a significant case that shook the hacker community was that of Jacob Appelbaum, a prominent hacker and former developer of the Tor project for online anonymity. In 2016, while he was still a regular visitor and speaker at CCC events, multiple women accused him of sexual harassment and misconduct. The gravity of this incident pressured CCC to pay extra attention to anti-harassment policies (Conger, 2017).

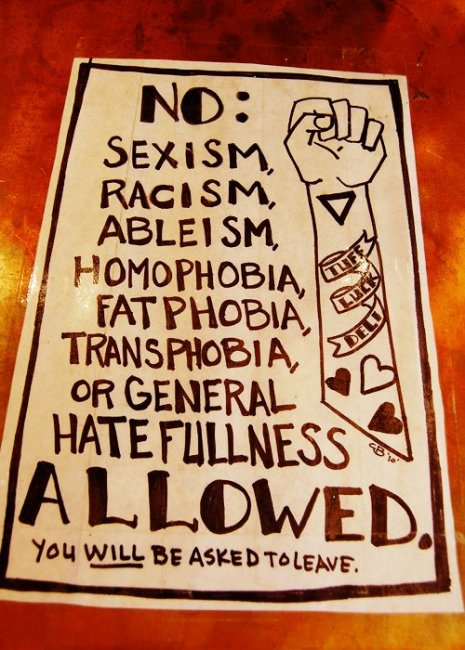

In response to reported issues of exclusion, harassment, hate speech, threats, and others, many tech conferences and FLOSS projects have broadly adopted Codes of Conduct (CoC). Such documents are useful for setting up rules and accountability, while also helping communities to formulate common values around their projects. The Ada Initiative, a US-based feminist organisation, started in 2011 to address issues of sexism in FLOSS communities, producing CoCs and anti-harassment policies. According to their description, an effective CoC should declare what are unacceptable behaviours and provide information about reporting violations and enforcing rules. There should also be a clear distinction between unacceptable behaviour, with severe consequences, and collective guidelines such as a general disagreement resolution (Aurora, 2014). For example, when someone is told to RTFM (Read The Fucking Manual), the community has to draw the line between structural exclusion and personal annoyance. What’s more, for actual interventions to happen, people need to constantly interact with the written rules of their community. The bodies gathered around Codes of Conduct are responsible for activating and enforcing them (Snelting, 2018).

Fig. 4: Do-ocracy poster, Noisebridge hackerspace, San Francisco

Chapter 2 - Exclusions in the geekdom

Openness and structurelessness

There is an active ongoing debate about the severe gender imbalance in the tech industry and open-source communities. Mary Gardiner, open-source developer and co-founder of the Ada Initiative, mentions that “people are scratching their heads over why women would avoid such a revolutionarily free environment like Free Software development” (Gardiner, 2009). Many doubt that any bad incidents have even happened. What if women are just not interested, or naturally not inclined to science and technology? A variety of feminist initiatives provide answers to such questions. In 1987, a mailing list called Systers was founded by Anita Borg to support women in computer science and related fields, in response to issues of sexism and patriarchal domination in physical and virtual spaces. The name Systers derives from the combination of the words systems and sisters. Jean Camp, an American scholar of informatics, explains how the Systers list provided a safe place, in a hostile net:

Consider a Usenet newsgroup specifically started to discuss issues about women: soc.women, where the posts by men outnumber women’s …. Too often, when women try to create spaces to define ourselves, we are drowned out by the voices of men who cannot sit quietly and listen …. So we withdraw to a room of our own (Camp, 1996).

Apart from being committed to FLOSS, hackers are often passionate advocates of free speech and expression. The culture of openness also extends to their spaces. Noisebridge, a hackerspace in San Francisco, states that it is free and open to everyone, imposing only one rule: “Be excellent to each other” (Noisebridge, n.d.). Such abstract, yet well-intended suggestions, have been critiqued by scholars as insufficient in banning various forms of misbehaviour. Hacker culture has in cases tolerated sexist, misogynist and discriminatory expressions in the name of freedom of speech (Reagle, 2013). The most vulnerable hackerspace participants feel discomfort and stress due to the lack of formal guidelines to declare inappropriate behaviours (Nafus 2012).

Hackerspaces and FLOSS communities usually have informal organisational structures. They may assume that diversity and inclusivity will grow organically, but unfortunately, that’s not the case. On the contrary, these communities reproduce their dominant white, male, geek culture, that fails to invite or retain women, lesbian, gay, trans and queer persons, gender non-conformists and people of colour, among others (Toupin, 2014). In Tyranny of Structurelessness, American feminist Jo Freeman analysed the power relations within radical collectives formed in the context of the ’70s Women’s Liberation Movement. She argued that when a community is lacking formal structures, it will possibly end up favouring those who already enjoy gender, class or race privileges (Freeman, 1972). Therefore, structurelessness hides the informal power of specific individuals or cliques. When issues of exclusion are not discussed, they become invisible, a possible risk in all kinds of structureless groups, including feminist ones.

Documenting exclusions

In 2008, the Geek Feminism Wiki, followed by the Geek Feminism Blog in 2009, constituted an online space for feminists to document incidents of sexism and harassment in the tech industry, FLOSS projects, gaming, comic book fandom, conference rooms and social media (Geek Feminism Wiki, n.d.). As Mary Gardiner explains:

Some women had stories, some women didn’t …. Had you asked me in 2003 for troublesome incidents in Free Software …. I don’t know that [sic] I would have been able to give you examples of anyone doing anything much wrong. A few unfortunate comments about cooking and babies at LUGs, perhaps. Things started to change my awareness slowly (Gardiner, 2009).

Documenting and archiving creates a collective memory, producing counter-narratives that impact how women perceive themselves. A relevant example is the #MeToo hashtag, initially used by civil rights activist Tarana Burke in 2006. The hashtag became the symbol of a movement fighting against sexual harassment and assault, gathering women’s experiences and stories, spreading them in public spheres and social media channels, creating collective spaces for solidarity, healing, and activism. The Ada Initiative, besides working on anti-harassment policies and advocating for gender diversity, also organised so-called Ally Skills Workshops. As described on the website:

The Ada Initiative Ally Skills Workshop taught men simple, everyday ways to support women in their workplaces and communities. Participants learned techniques that work at the office, at conferences, and online (Ada Initiative, 2013).

Many of the founders and advisors of the Ada Initiative were also contributors to the Geek Feminism Wiki and blog, while also being founding members of intersectional feminist hackerspaces (Toupin, 2014). Although the Ada Initiative closed in 2015 and the Geek Feminism Wiki is currently in archival mode, their work has not finished. Projects like these act as an influence and inspiration for new initiatives and as a digital resource for feminists or people who want to learn more about feminist issues. They can activate awareness-raising communities around issues of sexism, harassment, discrimination, and violence, and together build ways for addressing these as individuals or collective bodies.

Fig. 5: “Not afraid to say the F-word” stickers

We hear, but do we listen?

In 2019, technology and media scholar Danah Boyd received a Barlow/Pioneer Award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). Her inspiring acceptance speech titled Facing the Great Reckoning Head-On is a call for people in tech to consider their role in the toxic environment of injustices in which they are involved. (Boyd, 2019). That same year, MIT was pressured to apologise for accepting huge donations from Jeffrey Epstein, the American billionaire financier and convicted sex offender. Furthermore, Richard Stallman was pressured to resign as president and board member of the Free Software Foundation after defending the behaviour of Marvin Minsky, an AI pioneer and associate of Jeffrey Epstein. Danah Boyd’s call for personal and institutional reckoning was not only about these particular cases, but about the broader patriarchal structures that are still strongly upheld in tech institutions, academia, and elsewhere.

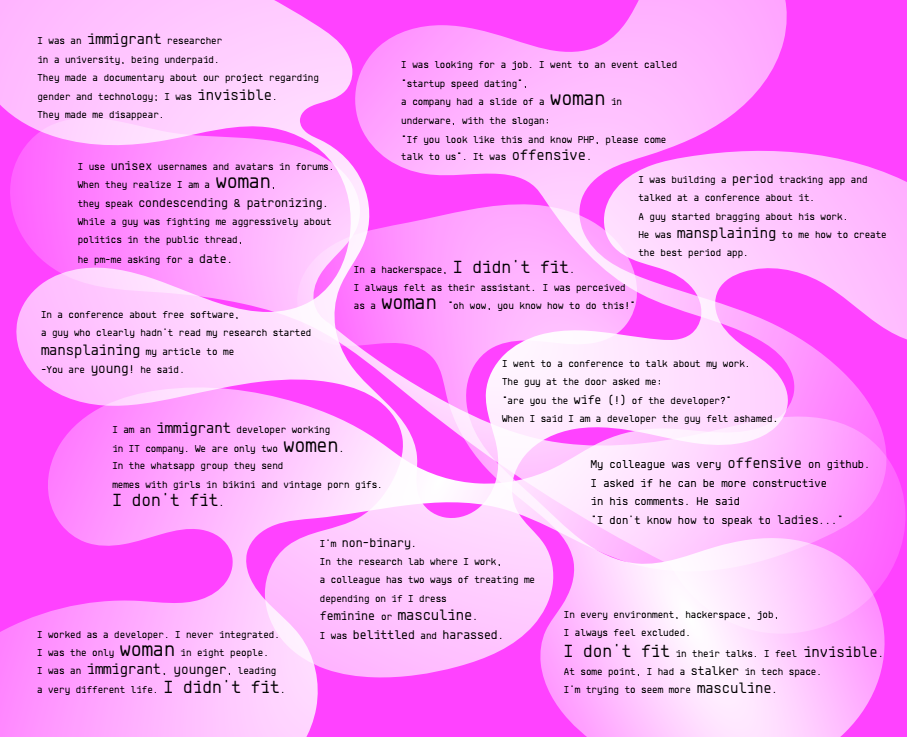

Responding to this call, I feel responsible and accountable. I carry on my back the injustices that happen, the hate, harm, cruelty. To start with, I propose to listen to those who are hurt, to those who feel excluded due to their social and political identities, which are intertwined and inseparable. Also, I want to make my small contribution to amplifying the stories of people who take action and constructively transform current reality. In 2019, I participated for the first time in the Eclectic Tech Carnival (/ETC), a feminist hacker event which will be presented in more detail in Chapter 3. The diverse sessions, workshops and discussions of /ETC inspired me to launch a series of similar gatherings, on a local scale. Together with Angeliki Diakrousi, Greek media artist and researcher, who contributed in organising this year’s /ETC, we became part of two parallel initiatives, in Athens and Rotterdam, aiming to explore the suggestions, urgencies and potential of feminist hacker communities. Our first meeting happened during the Carnival in Athens. It was a story-sharing session about people’s experiences of exclusions in tech, from a microaggression that took place at work, to a severe sexist incident. It is time to listen.

Xperiences was a gathering of women, trans, non-binary, and intersex people active in the tech world. The participants talked about their experiences as workers in the tech industry, as contributors in FLOSS movements, as initiators of inclusive hacker communities, as technology researchers in academia and as social media users. Their stories came out slowly, even hesitantly at first. Then they rushed out, they couldn’t be stopped. The atmosphere became emotionally tense, and people were thanking each other for the very reason that they can be there, without having to endure any forms of restlessness of the kind that they have experienced in other tech spaces.

Fig. 6: Illustration that borrows content from the Xperiences session at ETC 2019

Chapter 3 - Feminist hacker initiatives

Hacker praxis, with its contradictions and conflicts, has inspired diverse groups of people in various contexts. Feminists, who believe in the emancipatory potential of hacking, started shaping communities of their own. They have multiple good reasons to do so: disagreements on how mainstream hackerspaces operate, issues raised because of a problematic and abstract openness, reproduction of sexist behaviours, among others. Bravely enough, they appropriate the sacred term of hacking, combine it with feminist pedagogies and stretch it to acquire new meanings (Toupin, 2015). This chapter presents the practices of particular feminist hacker projects, exploring their urgency and potential. Specifically, it focuses on: the GenderChangers Academy (GCA), a series of women-only skill-sharing meetings, initiated in the early ’00s; the Eclectic Tech Carnival (/ETC), an international annual feminist hacker event; and the TransHackFeminist convergence (THF!), an annual gathering of queer feminist and visionary hackers.

Women-centred spaces and their opponents

Chapter 2 of this essay demonstrates how openness and structurelessness in hackerspaces are linked to the reproduction of privileges and social hierarchies. Feminist hackers use a variety of approaches to face this matter. Some choose to act inside existing hacker and open-source communities, pressuring them to revise their guidelines, while others prefer to form their own women1-centred spaces. The creation of safe-spaces that prioritise or even allow only the participation of minority groups is an old tactic used by feminists. It aims to set clear boundaries which ensure the safety and empowerment of identities traditionally excluded from a space or field. Feminist interventions, both inside and outside the realm of mainstream hackerspaces, are valuable in the context of diversity advocacy. It’s up to the community’s members to decide what’s critical for them, depending on where, when and how they operate.

Critiques of women-centred spaces claim that separatism in the long term may engender what is supposed to fight: isolation and exclusion. The safe-spaces tactic though, is only about participating in these specific groups, whereas each member also takes part in non-exclusive events and practices. It is a means, not a goal; an urgent step that feminist hackers take, in order to form their own voice and identity. The male-dominance of tech and hacker groups depicted in the previous chapters justifies the urgency to do so. Other critiques, compare feminist separatism with tactics used by men’s rights activist (MRA) and alt-right groups. However, this is an unsuitable correlation, as in the latter cases, exclusivity has an utterly different purpose, that aims to amplify existing power structures and imbalances. In the words of Faith Wilding and the Critical Art Ensemble in Notes on the Political Condition of Cyberfeminism:

It should be remembered that separatism among a minoritarian (disenfranchised) group is not negative. It’s not sexist, it’s not racist, and it’s not even necessarily a hindrance to democratic development. There is a distinct difference between using exclusivity as part of a strategy to make a specific perception or way of being in the world a universal and using exclusivity as a means to escape a false universal. There is also a distinct difference between using exclusion as a means to maintain structures of domination, and using it as a means to undermine them (Wilding, F. and Critical Art Ensemble, 1998).

Genderchangers

The Amsterdam Subversive Center for Information Interchange (ASCII), was one of the early hacklabs starting in 1999 as a free internet workplace in the Netherlands. ASCII was a technological as well as political space, part of squatting culture and anarchist movements. Most people running the ASCII were men, with backgrounds in engineering or computer science, and experienced with pirate radios, electronics or coding. Donna Metzlar is among the handful of women who frequented ASCII during the late ’90s. Officially trained as a nurse, she became fascinated with computers and started working as a system administrator, while being involved in many social and political activities, organising multiple workshops, events and feminist projects. She is one of the core members of Genderchangers, and a co-founder of the Eclectic Tech Carnival, Girl Geek Dinner Amsterdam and the Systerserver. Recalling her experience in ASCII, she narrates:

The very few women who were active in the space were concerned about the same thing. When you asked one of the guys in ASCII to help you or explain something, like how can you install LINUX on your machine, all of a sudden they just take over, and they start telling long stories with jargon that you can’t follow (in-person Interview, 16 Nov 2019).

The women of ASCII created the initiative of GenderChangers2 Academy (GCA), driven by their frustrations about the ASCII space. GCA started in the early ’00s as a women-only gathering, with the motive to exchange technical skills, unimpeded by the typical competitiveness of male geeks. In their first learning circle, they helped each other to install Linux on their computers collectively. Their gathering went so well that they decided to initiate a series of workshops to make more women interested in technology and free software. They bonded on issues that were beyond technology. Men running the ASCII didn’t welcome their initiative at first, and didn’t recognise the actual problem of homogeneity in the space. It took many fights, long discussions, and an incident of someone throwing away the women’s hardware until GCA gatherings were finally accepted. Eventually, men of ASCII were even proud that this was happening at their space, but it took time, insistence and effort.

Fig. 7: Genderchangers logo

/ETC

The Eclectic Tech Carnival (/ETC3 started as a Genderchangers-on-the-Road event, but eventually developed into an international project of its own. That probably happened because most of the initiators of the project were not coming from Amsterdam, but also from Canada, Sweden, the UK, South Africa, USA, Germany, or Australia. /ETC became an annual gathering of feminists, who critically study, use, discuss, share and improve everyday information technologies in the context of free software and open hardware movements. /ETC, like Genderchangers, was at first a women-only event. Over the years, the network of feminists who contribute to organising the /ETC event grew to respond and adapt to new contexts. The community regularly reassesses the choice of a being women-centred group. Currently, it supports the participation of people across a spectrum of gender, women and female-identified, transgender and queer persons. (/ETC, 2019).

Feminist hacker politics

Feminist hackers take a clear position against patriarchy through the fact of their very existence. They aim to bring feminist thinking and action in technological spaces, taking a step toward escaping unbalanced power systems. Alongside this fight, other political perspectives appear, including intersectionality, anticolonialism, and anticapitalism. Since feminist politics and analyses aren’t monolithic, several directions can coexist, overlap, or be avoided, depending on the context and circumstances.

Intersectionality

THF!

The first TransHackFeminist (THF!) convergence took place in Calafou, in the summer of 2014. Calafou is a network of cooperatives, individual projects and housing in a collectivised area in Catalonia. THF! includes discussions, workshops and sessions where intersectional feminists, and queer and trans people of all genders, gather to work together and discuss various subjects. THF! adopts an intersectional feminist approach. This framework emphasises the complexities brought by the intersection between gender, sexual orientation, geographical location, ethnicity and class, among others (Toupin, 2014). Intersectional feminist hacker groups recognise that hegemonic forms of feminism have historically promoted a white middle-class women’s agenda to the exclusion of others. Thus, they focus on shaping conditions in which relationships of domination are addressed and challenged.

THF! is about being aware of, and acknowledging, one’s privileges. It is about understanding the relations between privilege and oppression. A THF! practice is about being anti-racist, anti-capitalist, anti-sexist, anti-ableist, anti-homophobic, anti-transphobic, and using hacking as a means of resistance, sabotage and transformation (THF! Convergence Report, Calafou, 2014).

Fig. 8: TransHackFeminist Agreement

Decolonizing technologies

“Decolonizing technologies” was one of the focal themes during the third iteration of THF!, which took place in Montreal in 2016. The open call for the convergence states:

How then can we imagine the decolonization of technologies and of cyberspace? What would such processes, epistemologies, and practices entail? How can feminist anti-colonial, post-colonial, and/or indigenous frameworks shape and strengthen our analysis in our collective reflection on such questions? At the methodological level, can radical speculative fiction or storytelling a la Octavia’s Brood (2015) help us produce our vision(s) of decolonized technologies? In this stream we will explore the intricacies of colonial technologies while at the same time trying to conceive what decolonial technologies mean (THF! Summary, Montreal, 2016).

Here the organisers of THF!, propose to implement feminist, indigenous, and postcolonial or anti-colonial analyses when exploring complex political subjects, such as how colonialism invades technologies and cyberspace. For example, in the book The Undersea Network, researcher Nicole Starosielski described the inherent and continuous colonial relationships that are embedded in the infrastructure of the internet (Starosielski, 2015). Discussing such historical cases and choosing decolonising technologies as one of the main topics for THF!, highlight what is at stake, in the broader political directions and goals for TransHackFeminists. Also, the experimentation with speculative fiction is a feminist suggestion to reconfigure hacking and imagine how non-oppressive technologies could be shaped.

Anti-capitalist trajectories

During the first THF! convergence, the participants discussed what Trans-Hack-Feminism means as a whole. TransFeminism (TF) already existed as a concept with two main trajectories, one appearing in the context of the US, and one in the context of Spain. The Spanish THF! underlines the anti-capitalist principles and politics of the movement:

For Spanish participants particularly, TF is about making explicit the link with anti-capitalist perspectives in contrast with the US tradition where this direct connection is either not present, or not made so explicit (THF! Convergence Report, Calafou, 2014).

In the case of /ETC, the community takes a clear stance in opposition to tech and hack meetings organised by corporations which aim to increase the participation of women, femmes, and ethnic minorities in the tech industry. As explained in the website:

We don’t believe that identity diversity of big tech companies’ CEOs, or more gender diversity in supporting the capitalist system to sell more technology, is going to produce an egalitarian society. We want more feminists creating alternatives to those companies. We want more feminists knowing about technology so that they can challenge the system producing that technology (FAQs - Eclectic Tech Carnival, n.d.).

Social structures, technical infrastructures

In the European context, the feminist hacker initiatives I have encountered connect to what Peter Maxigas has described as the first hacklabs of Europe. These hacklabs had an overall political direction, linked with autonomous movements and media activism, where pirate radio, as well as independent publishing practices, emerged. A highlight of that period was the rise of Indymedia, the Global Network of Independent Media Centres (Maxigas, 2012).

Fig. 9: Computer hardware crash course at /ETC 2019

Fig. 10: Burner mail servers workshop at /ETC 2019

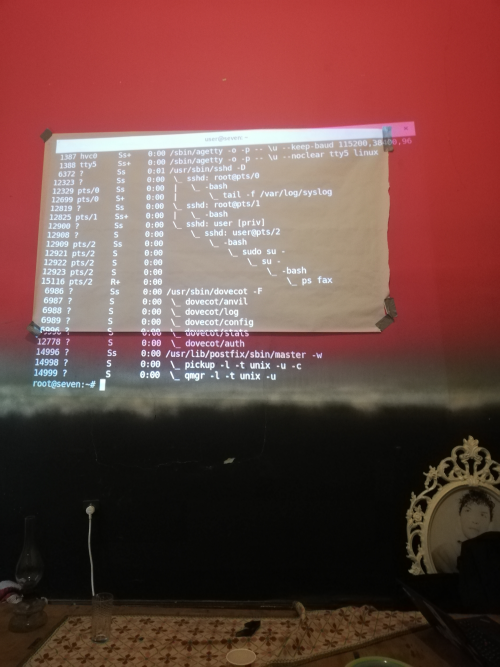

In Chapter 1, hacktivism was mentioned as the political stream of hacking: organising radical disruptions and attacks. Furthermore, hacktivism also focuses a great deal of its efforts on the creation of tools to protect from mass surveillance, infringement on privacy rights, governmental and business exploitation of users metadata, etc. Feminist hacker groups include such practices in their gatherings, workshops and thematic events. To better understand how this might look concretely, past workshops and sessions of /ETC have included: computer hardware crash courses; introductions in decentralised chat applications and creation of burner email accounts for anonymous messaging; production of DIY shielding bags that prevent mobile phones from being tracked; and lectures on autonomous technical infrastructures for horizontal communities (/ETC, 2019).

As far as the TransHackFeminist community is concerned, they have expressed in their writings, an aspiration to understand, use and eventually develop technologies for social dissent. In the event’s report from 2014, we can read:

The participants of the THF! understand technologies and hacking practices in the broadest sense; this includes hacking the body, gynecology and gender hacking, as well as academia, parenthood, and also computer systems, distributed networks, autonomous servers, pirate, community based and/or independent radio/tv, hardware and electronics (THF! Convergence Report, Calafou, 2014).

Feminist servers

Autonomous servers are part of a broader movement of autonomous technical infrastructures, deriving from the Appropriate Technology (AT) movement of the ’70s and ’80s. AT became a worldwide grassroots movement that influenced various groups of technologists (Pursell, 1993). A feminist server, in particular, is a concept that combines the interest for technical autonomy with feminist urgencies. It is an ongoing effort emerging from the need to ensure that works, publications, data and memories of feminist communities are properly accessible and managed. Feminist hacker initiatives work to provide technical literacy and the means to ensure that mailing lists, pads, wikis, content management systems, social networks and other feminist online services are preserved and protected.

During the /ETC, I learned about two active feminist server initiatives. These are:

1. Systerserver, a project launched by the Genderchangers and /ETC. It is run and maintained by women and acts as a place to learn administration skills, while it also hosts online services. (SysterServer, n.d.)

2. Anarchaserver, installed in 2014 during the first THF!. It hosts a wiki for the documentation of the THF! and a feminist blogging platform (Anarchaserver, n.d.). THF! describes that the need for feminist servers is a response to:

The unethical practices of multinational ICT companies acting as moral and hypocrite censors; gender based online violence in the form of trolling and hateful machoists harassing feminist or women activists online and offline; the centralization of the internet and its transformation into a consumption sanctuary and a space of surveillance, control and tracking of dissent voices by government agencies among others (THF! Convergence Report, Calafou, 2014).

Backstage communication tools

In an effort to control the technologies that mediate their social relations, feminist hacker groups choose alternative, decentralised, and open-source tools for their backstage communication. Contacting with people involved in /ETC and SysterServer, I understood that this is a political and cultural decision. Hacker groups in general, and feminist tech groups in particular, are opposed to the massive centralisation of the internet. Platformization offers giant tech companies, like Facebook and Twitter, the ability to establish themselves as unavoidable passages for everyone’s mundane social interactions.

Corporations now act as mediators of our communications and in turn, manipulate how we understand the world around us (THF! Convergence Report, Calafou, 2014).

Feminist hackers prefer to meet in online spaces such as mailing lists and Internet Relay Chat (IRC) channels. IRC is used to organise events and meetings, to set tasks of the day and to collectively work on projects. While IRC channels are public, one must know the channel name and network in order to join. That usually happens through word-of-mouth among trustworthy individuals, thus creating small-scale community discussions. Mailing lists of projects are private and moderated, though everyone can request a subscription. Their purpose is to continue general discussions initiated during events, to help each other in the process of learning things, to keep in touch, and to provide information about new projects.

While discussing with a software developer friend about IRC and mailing lists, his reaction was: “Oh, why do you use these primitive, museological tools?” In hacker circles, exploring alternative tools of communication is a practice of critical technology adoption. It aims to avoid mainstream social media monopolies, willing to comment on their drawbacks (Maxigas, 2017). Apart from using alternative tools to communicate, feminist hackers also organise self-learn meetings and hands-on workshops to explore a variety of technologies that are rooted in libre/free culture.

Liberation technologies for us mean taking back the control of the internet, infrastructure, algorithms, inscribing new values in code, among others (THF! Convergence Report, Calafou, 2014).

Hacking with care

Sociality and care are at the centre of attention for feminist hackers. Processes, behaviours and relations of people who work together on a hacking project are valued even more than the project itself. This is observable through the integration of various practices of care in different events and spaces. The organisers of the third iteration of the THF! chose Hacking with Care as a central topic for their discussions and activities. For them, focusing on well-being and on understanding oneself and others provides a basis for solidarity and maintains a network of trust.

With Hacking with Care, we wish to contribute to the resiliency and prosperity of what we see as an extended network of caregivers: hackers-activists, lawyers, journalists, artists, whistle-blowers, and many others with or without a profession or a name, distant and near, free and imprisoned, each and everyone of us a node in this human support network (THF! Summary, Montreal, 2016).

For the communities of Genderchangers and /ETC, spaces where people can ask so-called stupid questions amongst themselves, are explicitly needed. During an /ETC 2019 workshop about installing burner mail servers, I remember encountering multiple technical problems and feeling anxious about slowing down the rest of the group. When Donna and Juga, the workshop organisers, paused their presentation to help me, I received a significant moment of care which contrasted with past experiences in competitive tech environments. Attitudes like RTFSC (Read The Fine Source Code) are highly present in physical or digital tech spaces, causing amateurs and newbies to feel unwelcome and ashamed. This often leads to a habit of self-censorship and, if not addressed, may transform into a cause of exclusion.

Introducing non-technological activities is a gesture to invite amateurs or people from diverse backgrounds to be involved in hacker events. Past /ETC workshops have included botanology, healing, video art installations, sound performances, singing, and other practices that are often undervalued by techies. Also, including sessions for embodiment and mindfulness, like morning yoga, or evening walks to have time away from the screen and relax, is another expression of care during feminist hacker meetings. In THF! 2016, the organisers set up a tent, to offer space to sleep, rest from other intense activities or gather in a more private and calm environment.

During an informal conversation with an /ETC member, we discussed how providing childcare during a hacker event would be essential in inviting more mothers, as they usually face many difficulties in finding time and energy to participate due to their parental responsibilities. The HackerMoms space in Berkeley, California, was created to specifically address this issue, providing a playroom and a private space for breastfeeding, as well as childcare (HackerMoms, 2017).

Additionally, since most feminist hacker events are self-managed, caring to organise meetings to decide, review and discuss the practices of the community is a precondition. During the /ETC in Athens, there was an assembly every morning, in which participants talked about the tasks of the day and assigned roles for everybody to contribute in the ways they can. Responsibilities included cooking, recycling, cleaning, documenting, informing and supporting in workshops. Moreover, on the final day of the Carnival, the organisers called for a review session where people could share their thoughts, feelings and frustrations during their participation. This gathering created space for improvement based on solidarity and accountability.

Challenges

Feminist hacker initiatives, like other self-organised and self-sustained projects, encounter a variety of concerns, which have to do with sustainability, labour-power, engagement, participation, financial sources, maintenance, and more.

To start with, the physical space in which a community operates is worth considering, as it brings significant consequences. For instance, the political decision to operate in a squatted building means facing the risk of eviction. The ASCII hacklab that hosted Genderchangers during the ’00s started as a squat. After its legalisation, it faced a 900% rent increase that was impossible to afford, so activists squatted it again (ASCII, n.d.). Finally, it was evicted permanently in 2006, leading to the end of the hacklab at that location. The hardship of grassroots communities to find available and affordable places to host their initiatives is one of the reasons why they can be unsustainable.

Also, local groups that pop up in different countries, inspired by international events, such as the Eclectic Tech Carnival, sometimes struggle to attract an adequate amount of people who are interested both in technology and feminism. Additionally, the controversial subject of womxn4- centred spaces is in many cases the reason for political conflicts. As far as financial issues are concerned, each group follows different approaches. Crowdfunding methods are the most common, relying on solidarity bonds among interconnected community networks. Some groups may also choose to apply for funds, from organisations that support feminist perspectives.

Furthermore, the organisers of an international feminist tech event inevitably face multiple bureaucratic and political obstacles, according to the social, political and economic conditions of each hosting country. Aileen Derieg, translator and author, actively involved in the independent art scene in Austria, has been a member of the Genderchangers and co-organised the Eclectic Tech Carnival 2007. In her essay Things Can Break, she describes the distinct problems that occurred during the organisation of /ETC in Timisoara and Linz. In Timisoara, Romania, in 2006, the international and local organisers faced the issue of not having any basic infrastructure, even electricity, to set up the event. It required extensive efforts and hard work, to finally make it happen. On the contrary, in Linz, Austria, the next year, there was already well-established equipment and infrastructure available, though in that case, other hurdles appeared:

When announcements were sent out that registration for /ETC 2007 in Linz was open, over twenty registrations were received from Africa, mostly from Ethiopia and Ghana. After it was made clear that, as an all-volunteer effort, /ETC had no funding whatsoever for travel costs, only two women were left who succeeded in obtaining sponsorship for their travel costs, but they still had to apply for a visa to enter Austria in the heart of Fortress Europe (Aileen Derieg, 2007).

The differences in travel permits and restrictions that apply to various parts of the world make the conditions for people to participate in international events unequal. At /ETC 2007, long hours of communication and cooperation from the organisers were necessary, in an effort to overcome several complications. Finally, only one woman from Africa was able to acquire a visa to participate in the Carnival. All these impediments faced by feminist hacker communities, sometimes result in postponing or freezing their events. However, it usually takes only one person’s energy to motivate others and revive these projects. Above all, these collectives have continued to exist and reproduce, despite their small scale, since the early ’00s, because of their passion, dedication and enthusiasm. As Donna Metzlar describes:

We don’t have an agenda of creating profit or becoming famous. The event is very organic, it just happens and grows. All the friendships among our community have grown out of our events and meetings. We have cultivated this little subculture to work together. Doing work is just as important as spending time together. We learn and understand where someone’s strengths and weaknesses lie. I don’t get angry when somebody promises to do a poster and they don’t make it. Oh well, that’s probably because she is working at the moment, or she is having problems with her partner etc. It’s fascinating to see all of these women, dedicating hours and hours, for these events to happen. New people meet old members and decide to build new initiatives in their hometowns. It certainly has a network effect. The energy, the positivity, gives power to more people. When I was a girl scout, and we went hiking in the mountain, the rule was that you travel at the pace of the slowest. If you’re alone in the mountains, you won’t survive a storm. After all these years, I’m still here. This is all my own choice, and I enjoy it (in-person interview, 16 Nov 2019).

Although there are still many obstacles to overcome, the practices of feminist hacker communities are valuable on many levels: pedagogical, social and political. The dedication of systers in organising and following meetings, events, in travelling to find each other, in working hard to keep their culture alive, in solving their conflicts, I believe will go on and inspire others for years to come.

Epilogue

This essay unfolds the phenomenon of gender exclusions appearing in current male-dominated tech and hacker culture, and it presents various feminist approaches that respond to this issue. At first, it looks at the genealogy of hacking, in an attempt to interpret and contextualise the creation of a massively white, male field. It observes how the complexities of hacker ethics and aesthetics brought the rise of the hacker, as a title of honour. It questions who fits in hackerspaces and unpacks abstract claims for openness that rather hide the reproduction of privileges in existing power structures. Womxn*, as minority groups in the field of networked computing, have, since its early years, felt the urgency to gather in their own online spaces, to organise defence methods against sexism and harassment incidents, to support each other and to create solidarity bonds. Their shared stories, memories and hurtful experiences, documented in mailing lists, wikis, blogs, Usenet groups and IRC channels, started to form their collective identity; they became sisters in the field of systems, aka systers.

This year was the starting point for me to meet, research and contribute to the ventures of systers and feminist hackers. I discovered their long existence in online spheres, and I learned about their initiatives to create physical feminist hackerspaces. I consider the latter to be a step that can solidify the footprint of their communities and make their microculture more visible and accessible. Feminist infrastructures and networks of care are valuable for people who are active in tech environments, yet hesitate to bring up the issues they face, for fear of losing their job, being attacked or ridiculed, or losing balance in their social relationships. They are also useful for those who would be part of tech projects but have felt excluded from the start. Systers’ playful experimentation with technology and culture envisage utopian spaces, where compulsive morning routines, mundane work tasks and household responsibilities are temporarily on pause. I speculate that feminist hackers intend to hack the current tech-culture paradigm, as they materialise alternative spaces that set clear boundaries for safety. These spaces potentially act as sites to discharge political tensions. Systers’ activism also puts pressure on existing hackerspaces to change their norms and guidelines, an effect that has already started but is far from accomplished.

Feminist hacker initiatives appear increasingly in various forms worldwide, existing as instances among a wide range of gender equality movements. Together with #MeToo, #AintNoCinderella, #NiUnaMenos, #Aufschrei, #ΚαμίαΑνοχή, #OscarsSoWhite, and so many more, they create momentum for the reckoning of broader intersectional feminist perspectives. Sexism, misogyny, transphobia and racism are systemic social problems that shouldn’t be addressed as issues solely of the technological sector. Overcoming them requires constant effort in multiple sites, our jobs, our living rooms, our public spaces, our social media, our relationships. It would be unfair to expect from feminist tech grassroots communities to solve all these problems. Nonetheless, the existence of these communities is urgent, and their work moves towards the direction of social justice. As scattered islands of resistance, they exist with their inefficiencies, their imperfect or incomplete practices. They are syster systems, consisting of long-hour political discussions, feminist servers, crypto party choirs, draft hormone inspection devices, radio drama performances, workshops for e-textiles, disassemblies of old computers. These abundant eclectic activities raise two main questions: who counts as a hacker, and what counts as hacking? It’s about time to reconsider that there are no obvious answers.

Appendix

A Feminist Server Manifesto

In 2013, Constant, a non-profit, artist-run organization in Brussels, hosted the workshop Are You Being Served? During the session: First Feminist Server Summit, artists and activists reflected on questions around the potential of a Feminist Server practice. The collective discussions brought the following outcome:

A feminist server…

- Is a situated technology. She has a sense of context and considers herself to be part of an ecology of practices

- Is run for and by a community that cares enough for her in order to make her exist

- Builds on the materiality of software, hardware and the bodies gathered around it

- Opens herself to expose processes, tools, sources, habits, patterns

- Does not strive for seamlessness. Talk of transparency too often signals that something is being made invisible

- Avoids efficiency, ease-of-use, scalability and immediacy because they can be traps

- Knows that networking is actually an awkward, promiscuous and parasitic practice

- Is autonomous in the sense that she decides for her own dependencies

- Radically questions the conditions for serving and service; experiments with changing client-server relations where she can

- Treats network technology as part of a social reality

- Wants networks to be mutable and read-write accessible

- Does not confuse safety with security

- Takes the risk of exposing her insecurity

- Tries hard not to apologize when she is sometimes not available

Endnotes

-

Today’s feminist hacker communities usually uphold inclusive practices towards women, trans people, and gender-nonconformists. Each group may choose different terms or language, to critique both biological and social genders. The use of the term “women” often refers to a political category rather than a biological one (Dunbar-Hester, 2020). ↩

-

“We did not make up this term, we are re-using it. The tech industry created it. Technically and literally a gender changer is a computer part. It is an adapter that changes the "sex" of a port. Ports with pins are said to be male, ports with holes are said to be female. In the situation where two pieces of hardware both have the same port, an adapter saves the day and makes a connection possible. We are reclaiming the term to mean a person interested in the gendered aspects of technology.” (Genderchangers.org, n.d.) ↩

-

/ETC comes from the Unix file system directory which contains all the important configuration files for a computer and networking (hostname, hosts, networks), users (group), mail (mail.rc) and the rc.config and the directory init.d with the initialisation scripts. The name was chosen because it includes different aspects of socialisation and computer configuration (FAQs - Eclectic Tech Carnival, n.d.). ↩

-

The term womxn is an alternative spelling for the English word “woman”, rejecting its etymology from Old English wifmon (wife-man). “Womxn” is used in intersectional feminism, as it broadens the scope of womanhood, to include transgender and nonbinary women (Vibes, 2018). ↩

References

-

Ada Initiative (2013). Ally Skills Workshop. [online] Available at: https://adainitiative.org/continue-our-work/workshops-and-training [Accessed 29 April 2020].

-

Anarchaserver (n.d.). History of Anarchaserver and Feminists Servers. [online] Available at: http://anarchaserver.org [Accessed 29 April 2020].

-

Are You Being Served? → Summit_afterlife.md (2014). A Feminist Server Manifesto. [online] Available at: https://areyoubeingserved.constantvzw.org/Summit_afterlife.xhtml [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

ASCII, (n.d.). ASCII in trouble: 900% rent increase. [Electronic mailing list message] Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20160820212642/https://nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-0108/msg00123.html [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Aurora, V. (2014). ‘HOWTO design a code of conduct for your community’, Ada Initiative. [online] Available at: https://adainitiative.org/2014/02/18/howto-design-a-code-of-conduct-for-your-community [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Boyd, D. (2019). ‘Facing the Great Reckoning Head-On’, transcript, OneZero. [online] Available at: https://onezero.medium.com/facing-the-great-reckoning-head-on-8fe434e10630 [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Brand, S. (1972). ‘Spacewar: Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums’, Rolling Stone. [online] Available at: http://www.wheels.org/spacewar/stone/rolling_stone.html [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Brand, S. (1984). ‘Hackers’ Conference. Keep Designing, How the Information Economy Is Being Created and Shaped by the Hacker Ethic’, Whole Earth Review. [online] Available at: https://tech-insider.org/personal-computers/research/acrobat/8505-a.pdf [Accessed: 29 April 2020].

-

Calafou.org (2014). A Transhackfeminist (THF!) Convergence Report - Calafou. [online] Available at: https://calafou.org/en/content/transhackfeminist-thf-convergence-report [Accessed: 29 April 2020].

-

Camp, L. J. (1996). ‘We are geeks, and we are not guys: The systers mailing list’, in Cherny, L. and Weise, E.R. (eds), Wired women: Gender and new realities in cyberspace. Seattle, Wash.: Seal Press.

-

Coleman, G. (2004). ‘The Political Agnosticism of Free and Open Source Software and the Inadvertent Politics of Contrast’, Anthropological Quarterly, 77 (3): 507–519. doi:10.1353/anq.2004.0035.

-

Coleman, G. (2012). Coding freedom: the ethics and aesthetics of hacking. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

-

Conger, K. (2017). ‘Developer tells her story publicly as hacker community struggles to address sexual sssault’, Gizmodo. [online] Available at: https://gizmodo.com/developer-tells-her-story-publicly-as-hacker-community-1821652260 [Accessed: 28 April 2020]

-

Derieg, A. (2007). ‘Things Can Break. Tech Women Crashing Computers and Preconceptions’, Transversal texts. [online] Available at: https://transversal.at/transversal/0707/derieg/en [Accessed: 8 May 2020].

-

Dunbar-Hester, C. (2020) Hacking diversity: the politics of inclusion in open technology cultures. Princeton studies in culture and technology. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

-

/ETC - Eclectic Tech Carnival (2019). About The Eclectic Tech Carnival. [online] Available at: https://eclectictechcarnival.org/ETC2019/about [Accessed 29 April 2020].

-

/ETC - Eclectic Tech Carnival (2019). How is /ETC different from other hackmeetings and technology events? [online] Available at: https://eclectictechcarnival.org/ETC2019/faq [Accessed 29 April 2020].

-

/ETC - Eclectic Tech Carnival (2019). /ETC Schedule. [online] Available at: https://eclectictechcarnival.org/ETC2019/schedule [Accessed 29 April 2020].

-

European Commission, (2018). Women in the digital age final report. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/increase-gender-gap-digital-sector-study-women-digital-age [Accessed 29 April 2020].

-

Freeman, J. (1972). ‘The Tyranny of Structurelessness’, The Second Wave, 2 (1): 20.

-

Gardiner, M. (2009). ‘Why we document’, Geek Feminism Blog. [online] Available at: https://geekfeminismdotorg.wordpress.com/2009/08/19/why-we-document [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Geek Feminism Wiki (n.d.). Timeline of incidents. [online] Available at: https://geekfeminism.wikia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_incidents [Accessed 29 April 2020].

-

Genderchangers.org. (n.d.). Frequently Asked Questions. [online] Available at: https://www.genderchangers.org/faq.html [Accessed 29 April 2020].

-

GitHub, Inc. (2017). Open Source Survey. [online] Available at: https://opensourcesurvey.org/2017 [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Grenzfurther, J. and Schneider, F. (2009). ‘Hacking the Spaces’, Monochrom. [online] Available at: http://www.monochrom.at/hacking-the-spaces [Accessed: 21 Feb 2020].

-

HackerMoms (2017). FreakAtoms. [online] Available at: http://freakatoms.co.uk/2017/07/meet-mothership-hackermoms [Accessed 29 April 2020].

-

Henn, S. (host) (2014). When Women Stopped Coding, Morning Edition, NPR. [podcast] Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2014/10/21/357629765/when-women-stopped-coding? [Accessed 29 April 2020].

-

Jordan, T. (2017). ‘A genealogy of hacking’, Convergence, 23 (5): 528–544. doi:10.1177/1354856516640710.

-

Levy, S. (1984). Hackers: heroes of the computer revolution. Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday.

-

Maxigas, P. (2012). ‘Hacklabs and Hackerspaces—Tracing Two Genealogies’, Journal of Peer Production, 2. [online] Available at: http://peerproduction.net/issues/issue-2/peer-reviewed-papers/hacklabs-and-hackerspaces [Accessed: 21 Feb 2020].

-

Maxigas, P. (2017). ‘Keeping technological sovereignty: The case of Internet Relay Chat’, in Technological Sovereignty, Vol. 2. Barcelona: Descontrol, 67-82.

-

Morgan, A. (2014). ‘The Rise of the Geek: Exploring Masculine Identity in The Big Bang Theory’, Masculinities: A Journal of identity and Culture, 2: 31-57.

-

Nafus, D., Leach, J., Krieger, B. (2006). Gender: Integrated Report of Findings. Free/Libre and Open Source Software: Policy Support FLOSSPOLS, Deliverable D 16. [online] Available at: https://www.jamesleach.net/downloads/FLOSSPOLS-D16-Gender_Integrated_Report_of_Findings.pdf [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Nafus, D. (2012). ‘Patches don’t have gender, What is not open in open source software’, New Media & Society, 14 (4): 669–683. doi:10.1177/1461444811422887.

-

Noisebridge - a hacker space ship (n.d.). What is Noisebridge? [online] Available at: https://www.noisebridge.net [Accessed 3 May 2020].

-

Padilla, M. (2017). ‘Technological Sovereignty: What are we talking about?’, in Technological Sovereignty, Vol. 2. Barcelona: Descontrol, 3-15.

-

Pursell, C. (1993). ‘The Rise and Fall of the Appropriate Technology Movement in the United States, 1965–1985.’ Technology and Culture, 34 (3): 629–37. doi:10.2307/3106707.

-

Reagle, J. (2013). ‘Free as in sexist? Free culture and the gender gap’, First Monday, 18 (1). doi:10.5210/fm.v18i1.4291.

-

Snelting, F. (2018). ‘Codes of conduct’, in Sollfrank, C. (ed), Die schönen Kriegerinnen: technofeministische Praxis im 21. Jahrhundert. Vienna: Transversal Texts.

-

Spertus, E. (1991). ‘Why are There so Few Female Computer Scientists?’, MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory Technical Report 1315. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

-

Stallman, R. (2012). Interviewed by Theodoros Papatheodorou for OUGH!. [online] Available at: https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/ough-interview [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Starosielski, N. (2015). The undersea network. Sign, storage, transmission. Durham: Duke University Press.

-

Syster Server (n.d.). Adele, a Systerserver. [online] Available at: https://systerserver.net [Accessed 11 October 2019].

-

THF! - Transhackfeminist! (2016). Decolonizing Technologies. [online] Available at: https://transhackfeminist.noblogs.org/post/2016/07/17/thf-2016-third-transhackfeminist-meet-up [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Toupin, S. (2014). ‘Feminist Hackerspaces: The Synthesis of Feminist and Hacker Cultures’, Journal of Peer Production, 5. [online] Available at: http://peerproduction.net/issues/issue-5-shared-machine-shops/peer-reviewed-articles/feminist-hackerspaces-the-synthesis-of-feminist-and-hacker-cultures [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Toupin, S. (2015). ‘Feminist Hackerspaces as Safer Spaces?’, Feminist Journal of Art and Digital Culture, 27. [online] Available at: https://dpi.studioxx.org/en/feminist-hackerspaces-safer-spaces [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Turner, F. (2006). From counterculture to cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the rise of digital utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

-

Vibes, K. (2018). ‘Intersectional Feminism 101: What is Womxn?’, Medium [online] Available at: https://medium.com/@knottyvibescompany/intersectional-feminism-101-what-is-womxn-36c0a3140126 [Accessed: 28 April 2020].

-

Wilding, F. and Critical Art Ensemble (1998). ‘Notes on the Political Condition of Cyberfeminism’, Art Journal, 57 (2): 47–60. doi:10.1080/00043249.1998.10791878.

Image sources

-

Fig 1. Women in the digital age final report (2018). Labour market distribution of individuals in digital jobs by age and gender. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/increase-gender-gap-digital-sector-study-women-digital-age [Accessed: 14 May 2020].

-

Fig 2. Whole Earth Review (1985). Hackers Conference 1984. Available at: https://tech-insider.org/personal-computers/research/acrobat/8505-a.pdf [Accessed: 14 May 2020].

-

Fig 3. Free/Libre and Open Source Software: Policy Support FLOSSPOLS (2006) Survey respondents to the question: Regarding your collaboration with others during your FLOSS activities, have you ever observed or experienced discriminatory behaviour against women? Available at: https://www.jamesleach.net/downloads/FLOSSPOLS-D16-Gender_Integrated_Report_of_Findings.pdf [Accessed: 14 May 2020].

-

Fig 4. Noisebridge (n.d.). Do-ocracy poster, Noisebridge hackerspace, San Francisco. Available at: https://www.noisebridge.net/wiki/Do-ocracy [Accessed: 14 May 2020].

-

Fig 5. Ada Initiative (n.d.). ‘Not afraid to say the F-word’ stickers. Available at: https://adainitiative.org/category/support-the-ada-initiative/. [Accessed: 14 May 2020].

-

Fig 6. Gryllaki, A. (2019). Illustration that borrows content from the Xperiences session in ETC 2019.

-

Fig 7. Genderchangers (n.d.). Genderchangers Logo. Available at: https://www.genderchangers.org [Accessed: 14 May 2020].

-

Fig 8. THF! (n.d.). ** TransHackFeminist Agreement. Available at: *https://transhackfeminist.noblogs.org/community-agreement/ [Accessed: 14 May 2020].

-

Fig 9. Gryllaki, A. (2019). Computer hardware crash course in /ETC 2019. Athens: Personal Archive.

-

Fig 10. Diakrousi, A. (2019). Burner mail servers Workshop in /ETC 2019. Athens: /ETC Archive.

Colophon

This publication is based on the graduation thesis Syster Systems, written under the supervision of Marloes de Valk.

A heartfelt thanks to Marloes de Valk and Lídia Pereira for their feedback, help and support during the writing of this research. Special thanks to Angeliki Diakrousi, Donna Metzlar, /ETC Athens Crew, Amy Pickles, my fellow XPUB comrades, Aymeric Mansoux, Michael Murtaugh, Leslie Robbins, Clara Balaguer, Amy Suo Wu, André Castro, Steve Rushton, Femke Snelting.

[Artemis Gryllaki, Syster Systems, 2020. Rotterdam]. This work is published under the terms of the Peer Production License. The Peer Production License is an example of CopyFair licensing, in which only other commoners, collectives and nonprofits can share and re-use the material in question.