Tactical Watermarks

Introduction

I am a privileged student. I have always been part of universities where I had access to paywalled academic journals. The reality in academic publishing nowadays is one of universities and governments outsourcing the publishing of research papers to private companies such as JSTOR and Elsevier. These journals are maintained behind paywalls that demand payment of approximately 30 euros per article, making access practically impossible to anyone who is outside of institutions that have a subscription. Strategies such as watermarking are used by these companies to discourage the distribution of proprietary material, making users more easily liable for their actions. Book publishers enforce similar policies, where customers are not able to share files they have paid for. My research departs from the critical research question – how can publishing bypass surveillance, and which counter-measures play an active role within this process? I will look into the motivations behind alternative strategies that open access to published material. I will explore established reactive measures that help users evade surveillance in publishing. At the same time, I will question how we can tackle this problem through the reappropriation of digital watermarks.

I will start by addressing how analogue media has played a vital role in bypassing surveillance from oppressive regimes. At this moment, the mainstream usage of the internet enables files and political ideas to go viral among larger audiences. A wide variety of infrastructures exist to publish files that have been made exclusive, for a broad diversity of reasons, from protected governmental secrets to copyrighted material. In the first chapter, I will look into extra-legal libraries and archives, while also questioning the current impact of these spaces and their roles in preserving the digital memory of sensitive information.

In the second chapter, I will address how digital surveillance manifests itself through different channels. In the realm of publishing, the primary strategies focus on making users who illegally download, distribute, and share copyrighted material more accountable and more easily identifiable for their online actions. Publishers have started to limit access to illegal copies, by appending imprints such as the downloader’s geolocation, IP address, MAC address, email address, and others. What is the impact of constantly reminding readers that they can become targets?

The last chapter will focus on my project Tactical Watermarks, where I explore the use of watermarks as alternative forms of anonymisation. This chapter provides an overview of different creative responses, questioning authorship, protecting users’ identity, and appending evidence of hidden processes required to subvert surveillance in physical and digital media. As a publisher, I have always had as my main concern how archives are documented and how provenance is displayed. Converting physical media into digital files is hard, and information often gets misappropriated in the process. With Tactical Watermarks, I reflect on the shreds of evidence that make those who download and share accountable. As a response to these strategies of digital surveillance, I question how we can reappropriate and regain control over these personal traces.

Part 1 – Bridging between surveillance and publishing

Bypassing surveillance

To understand how corporations enforce digital surveillance, we must step back and recognise how censorship and surveillance have always been deeply connected in repressive authoritarian regimes. The reasons may differ, but the tools and goals are similar. Today in China and Turkey, reactive measures mirror the present state of surveillance. Actions such as restricting internet access, filtering content, monitoring online behaviour, or even prohibiting internet use entirely are put in place (Kalathil and Boas, 2001). These measures have political agendas: restricting the flow of culture and limiting freedom of speech is a way of avoiding dissent. Online strategies such as the use of virtual private networks and internet extensions play an essential role in establishing encrypted and secure connections online, thus providing privacy and helping users to bypass surveillance. These tactics bear a resemblance to how various analogue media have shaped parallel streams of prohibited communication throughout history.

After the Second World War, through the ’40s and ’50s, the Soviet Union made the circulation of art and music from the West illegal, making these kinds of cultural expression extremely limited. Against this, the stilyagi, members of youth counterculture in the Soviet Union, found a way to bootleg and smuggle Western records. While the main problem with DIY vinyl was acquiring the material to use in homemade record presses, a new method consisted of going through hospital dumpsters and collecting used X-ray sheets. Music would then be engraved in this vinyl X-ray material, and the middle hole to fit on the spindle would be burnt with a cigarette. More often than not, these types of vinyl would picture old images of bones and medical material, and started to be called music on the ribs, and bone records, creating space for a black market, leading to a cultural revolution (Grundhauser, 2015).

Figure 01 – Bone Record (Unknown, n.d.)

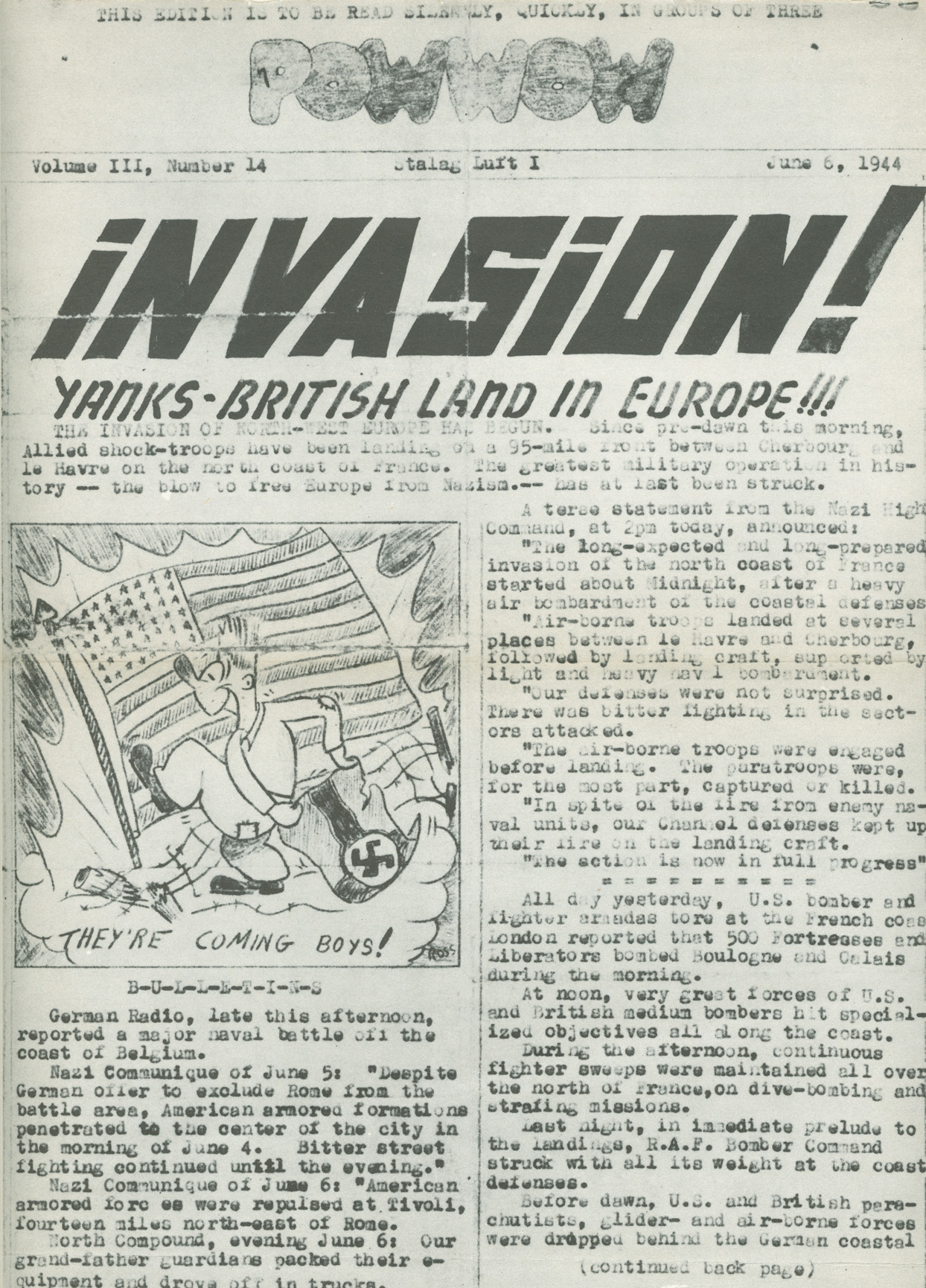

During the ’60s, within the American, Western European and Asian context, illegal or clandestine publications started to emerge. Dominant governmental, religious, or institutional groups would prohibit any publications that weren’t officially approved before publishing (Miles, 2016). The term underground press refers to all the underground periodicals and publications that arose associated with the counterculture of the ’60s and early ’70s. Underground periodicals were inspired by predecessors, such as the POW WOW, standing for Prisoners Of War - Waiting On Winning. POW WOW was a periodical published in Germany during World War II, considered “the only truthful newspaper in Germany”, and with the advice “to be read silently, quickly, in groups of three”. Prisoners of war published it in the Stalag Luft I camp in Nazi Germany to give insights on what was happening outside of the camp. It ended up being the most circulated daily underground newspaper in Germany during World War II (Smith and Freer, 2012). Another notable endeavour within the phenomenon of the underground press was samizdat, a do-it-yourself underground publishing movement that operated in the Soviet Union during the cold war (Kind-Kovács and Labov, 2015). Across the Eastern Bloc, readers would reproduce censored materials by hand, and these would be passed from reader to reader. Harsh punishments awaited anyone caught possessing these publications. Vladimir Bukovskiĭ gives an overview of this phenomenon as: “Samizdat: I write it myself, edit it myself, censor it myself, publish it myself, distribute it myself, and spend time in prison for it myself.” (Bukovskiĭ, 1988).

Figure 02 – POW WOW, D-Day, June 6, 1944, Front (Kuptsow, 1944)

Inspired by the free press and counterculture, zine culture started to emerge in the ’80s within the underground publishing panorama, emancipating print in order to overcome repressive power structures. Zines speak from and to an audience of underground cultures. Zines are self-published media, either with original or appropriated images and texts, with small-circulation and small-scale editions. Zines enable almost anyone to publish, making use of photocopiers and mimeographs for cheap and fast print runs. Zines are personal statements targeted to like-minded communities. Their positioning is somewhere between open letters and magazines, almost always not for profit, and even more commonly: publishers ended up losing money on them (Duncombe, 2017). The main thematics of zines are broad, from politics to pop culture. Networking zines also stand out, such as the Factsheet 5 periodical founded in 1982 by Mike Gunderloy. Networking zines were fundamental in broadcasting, indexing and publicising other zines – and, as a result, helping to spread these DIY publications, by increasing audiences and access to such published material, and leading to the beginning of the emancipation of self-publishing as a strong response to repressive regimes.

The circulation of zines is puzzling. Zines circulated among amateurs. Without its negative connotations, the word “amateur” (from the Latin amator) can be defined as “those who love”. With all the limitations that zines imply, all those who were involved, from publishers to readers, used this medium as a place to communicate and explore innovative ways of thinking (Duncombe, 2017). Printed zines were distributed by hand, and played a key role in engagement within smaller communities. Zines would circulate among trusted people only. This intimate movement of culture was significant when it came to building communities – more than simply spreading texts to be read, zines stimulated meetings between like-minded enthusiasts.

Contrasting fast-paced spaces

In contrast to the close circulation of material in zine culture, the way we circulate content online has changed. Digital media have been responsible for some of the most wide-ranging changes in society over the past quarter of a century (Schroeder, 2018). Our notion of control has adapted, and our perception of physical spaces may be changing how we perceive distance (Munster, 2011). The website GeoCities is an example of this phenomenon – founded in 1994 as Beverly Hills Internet (a name that didn’t last long), GeoCities was organised into different regions, for example “Hollywood” spaces were assigned to webpages dealing with entertainment, and “SiliconValley” to computer-related web-hosted areas. Not only these web spaces started to create a different perception between virtual and real spaces, but communities also evolved, remarkably inspired by what happened with distributing zines by hand. Users navigated within different web spaces organised around shared interests. Web pages were linked in webrings, collections of sites linked in a circular structure.

Currently, public discourse and discussions happen online. The circulation of media and opinions is now viral. Political statements penetrate internet spaces, often hidden, for exmple through memes. Memes function as a virus, as an easy way to propagate an idea. They are used by both the political left and right to spread their agendas. Memes are used to mask messages, and to evade digital censorship. They play a crucial role in present-day protests and are used by resistance movements as contemporary political posters (Metahaven, 2014). In China, the Grass Mud Horse meme gained popularity because of its ambivalence. While exploring a dual linguistic feature, it evades digital censorship. In Chinese, pronouncing Grass Mud Horse one way, refers to an innocuous mythical animal apparently related to the Bolivian alpaca. However, when pronounced another way, it means “fuck your mother” (肏你妈) (Wu, 2019).

Figure 03 – Grass Mud Horse (russelgz, n.d.)

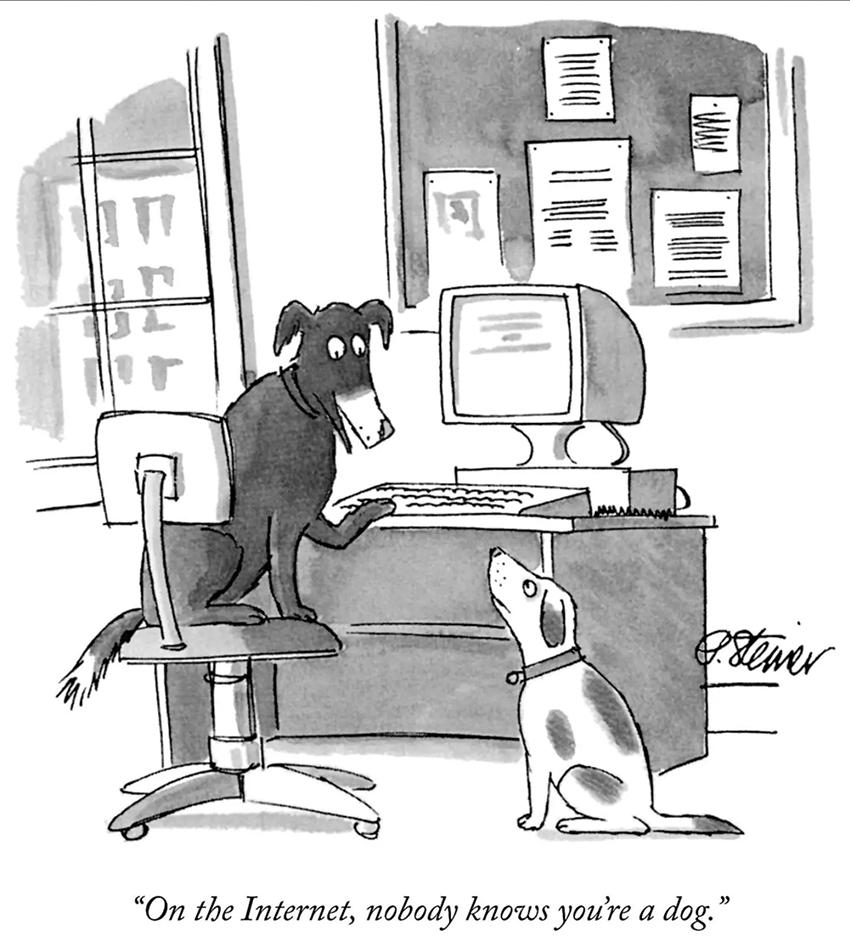

Analysing strategies that enable access

On July 5, 1993, The New Yorker published a cartoon by Peter Steiner with the caption: “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” (Steiner, 1993). It pictures two dogs interacting, one of which is sitting at a computer. This symbolised the understanding of internet privacy, where users could interact with a certain degree of identity anonymity. Now, however, things have changed: the use of nicknames and pseudonyms is not as prevalent, and a user is expected to display their real identity. Not only the use of a name is enforced, but it is almost mandatory to connect a face to this name. As an example, Facebook demands real names, abandoning pseudonyms and making us use our real identity. Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, even defends this position by stating that maintaining two or more identities is an example of a lack of integrity (Kirkpatrick, 2012).

Figure 04 – On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog (Steiner, 1993)

Corporations neglect users’ right to privacy. Technology to surveil and control the individual is expanding. Users are more liable for what they consume and share online. At the same time, companies become less accountable for what they do with users’ data (Mann, 2003). Lawrence Lessig points out that both in privacy and copyright, users have lost control over their data. There is a dire need for stricter regulations protecting the privacy of users, yet nothing is happening. When it comes to copyright protection, on the other hand, companies have pushed for regulations and have gotten their way (Lessig, 2008). When comparing these two interests, the right to privacy is not protected because the parties interested lack power and influence, unlike the entertainment industry which has the authority, the power, and the means to demand change.

Strategies to allow access to copyrighted materials and protected research journals have started to emerge. Because researchers kept bumping into expensive paywalls that were unaffordable for many, tactics were developed to make research more widely available. Online spaces such as archives and extra-legal libraries provide areas for accessing media through alternative channels, and their structures play a crucial role in who gets to access them. Users are filtered, restricting access to certain communities, protecting them and enabling curators to answer more specific needs. This user filter is implemented using tactics such as invitations, or requiring particular technological knowledge. When thinking about extra-legal publishing streams, we have to consider how these shape the way different digital files are accessed, and by which audiences. What are the available strategies and resources that enable public access? Here I will introduce infrastructures, policies, and tactics that protect those who host and make use of such platforms. Within shadow libraries, libraries that exist in the margins of the law, different systems exist: from public shadow libraries, where everyone is allowed to download and upload digital material, to more restricted libraries where proxies and invites are required.

Library Genesis started in 2008 as a successor to library.nu (previously ebooksclub.org and even earlier gigapedia.com). Between 2008 and April 2014, this library grew at a fast pace, with 1.2 million records by 2014 (Balázs, 2018). The website owners describe themselves as “random book collectors”, who don’t focus on curating materials and don’t accept file requests. The topics are broad: from economy and geology to housekeeping. All users are encouraged to upload and download content. There’s no upload score to maintain, no necessary login, and no price to pay. The platform regularly fights against shutdown attempts. Strategies to increase the lifespan of the collection are put in place, such as encouraging the creation of mirrors. Mirrors allow hosting voluntary copies of entire collections or parts of collections over different servers and points of access, making these more difficult to control or suppress.

Within its context, Library Genesis seems to distance itself from the idea of bringing academic research to people without access. Although this vast library supposedly gathers information without any specific methodology, the reasons behind it look more like a political statement against copyrighted material, rather than trying to please a particular crowd. The focus on dimension rather than curation provides clues to its primary goal: publishing as much proprietary content as possible, thus dissolving the idea of ownership. The main page of the website links to a letter of solidarity demanding for action, a manifesto for standing up for what they believe in, incentivising the dissemination of knowledge:

We find ourselves at a decisive moment. This is the time to recognize that the very existence of our massive knowledge commons is an act of collective civil disobedience. It is the time to emerge from hiding and put our names behind this act of resistance. (Custodians, 2015)

Another shadow library, aaaarg.fail, stands out because of the demographics of its users, who are mainly researchers, academics, students and people interested in theory. To become a member, you need to be invited, and it might feel like you are in a private club, where you won’t spot any advertising or demands for donations. Strategies, such as incorporating RSS feeds, creating a panel where users can discuss, and displaying a contact list on the landing page, allow users and moderators to connect more closely. As a member, you can not only upload and download but also request new titles through a message board, augmenting the sense of community and solidarity that exists in this online space.

Libraries such as The Library and the Clockwise libraries operate within the dark web. Standard web engines do not index their content. Instead, these libraries are indexed in specific webpages such as http://mx7rwxcountermqh.onion/. In such an index, you can find an annotated list of URLs, with a small description of the focus of each space. These libraries are harder to come across; you have to use Tor, the onion browser, to access them. They work as webrings, which brings a sense of community to the numerous projects that can be found here. Such archives appear to be personal libraries, for example the Pokedudes Archive of Interesting and Odd Files, which curates what is described as “a small list of weird or interesting files”.

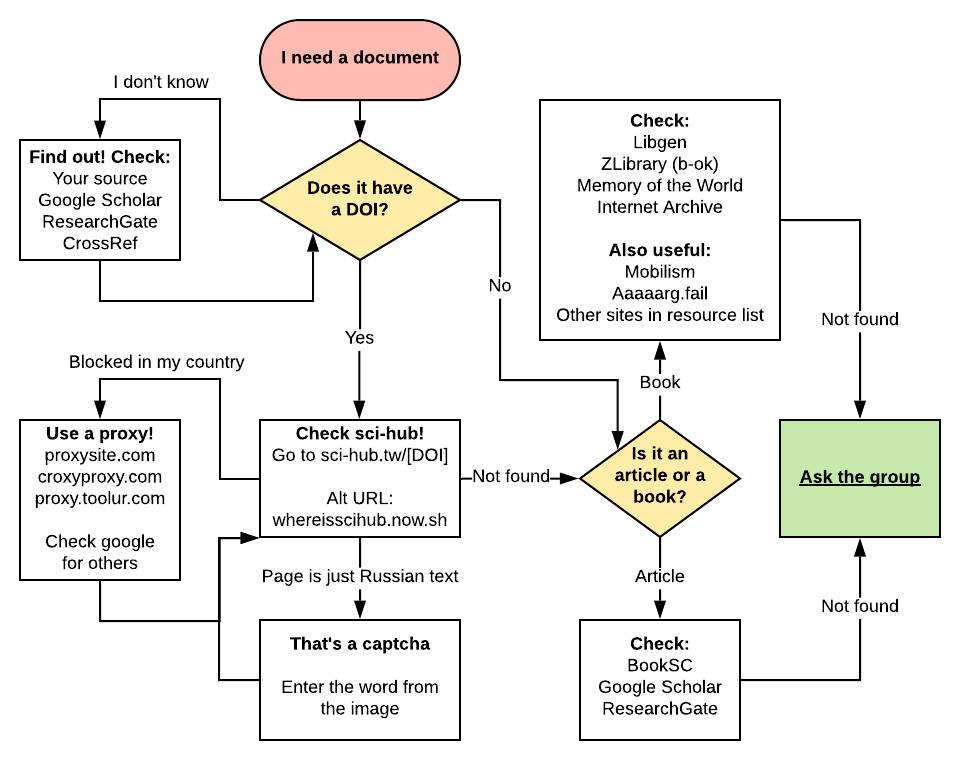

A more informal system of file sharing is a Facebook group titled Ask for PDFs from People with Institutional Access, which brings together people who are part of an institution, and people who are not and thus cannot afford research papers. The use of centralised social media to create an accessible community of scholars is fascinating. The appropriation of the design features of Facebook groups, such as the cover picture, is also compelling. The page displays a graphic (see figure 05) to help guide newcomers. This group transforms the act of sharing copyrighted material, making it into something more mundane and less specific to a hacker community. The workflow is as simple as if you were part of this group: you post asking for a PDF you need. Users interested in getting the same item comment “F” on the post, which stands for “following”. Due to the design of the platform, if you comment you will be notified whenever there is activity on the post. This is an informal community of academics, sharing items among themselves, uploading pirated material to this platform and creating a social library.

Figure 05 – Cover picture: Ask for PDFs from People with Institutional Access (Unknown, 2019)

Besides shadow libraries, systems also exist such as archives that document and organise perishable sensitive information. MayDay Rooms is an example where the infrastructures and the counter-strategies required to publish experimental culture play are equally important. MayDay Rooms is an educational charity founded as a safe haven for historical material linked to social movements, experimental culture and the radical expression of marginalised figures and groups. Originally set up to safeguard historical documents, it is more than just a digital archive. Online users can browse a catalogue and read PDFs, but MayDay Rooms also deals with physical items. The home for this archive is the Birmingham Daily Post’s former London office, which was refurbished in 2012 and 2013. This building is not only used as a space to preserve materials, or as an infrastructure for its digital archive: it also offers communal areas, such as reading, meeting and screening rooms, and a canteen. It is a place for informal researching, gathering, and activation of the social aspect of the archived materials – for example, by digitising and distributing them online (MayDay Rooms, n.d.).

After looking into shadow libraries and digital archives, strategies to distribute and preserve copyrighted material, the users of these archives and the political agendas behind them, my research will delve deeper into the phenomenon of watermarks. Watermarks are often used to identify the original owners of files as sources of copyrighted material, thus intimidating them, raising concerns of liability, and as a result, discouraging sharing. I will focus on this tactic of protecting intellectual property, and expand on how this technique is negatively impacting the sociability that comes with sharing texts, and restraining the flow of files within online digital spaces.

Part 2 – Sorting imprints

Background of watermarking

The internet as a carrier of digital media has changed how we share music, books, video and other media. The integration of digital watermarks is becoming more popular as a way to fight the fast-paced spaces opened to sharing pirated material. Currently, research on watermarks predominantly focuses on strengthening security: embedding robustness with respect to compression, image-processing operations, and cryptographic attacks (Shih, 2017). We now understand watermarks as being both digital and physical, but they are not a new phenomenon.

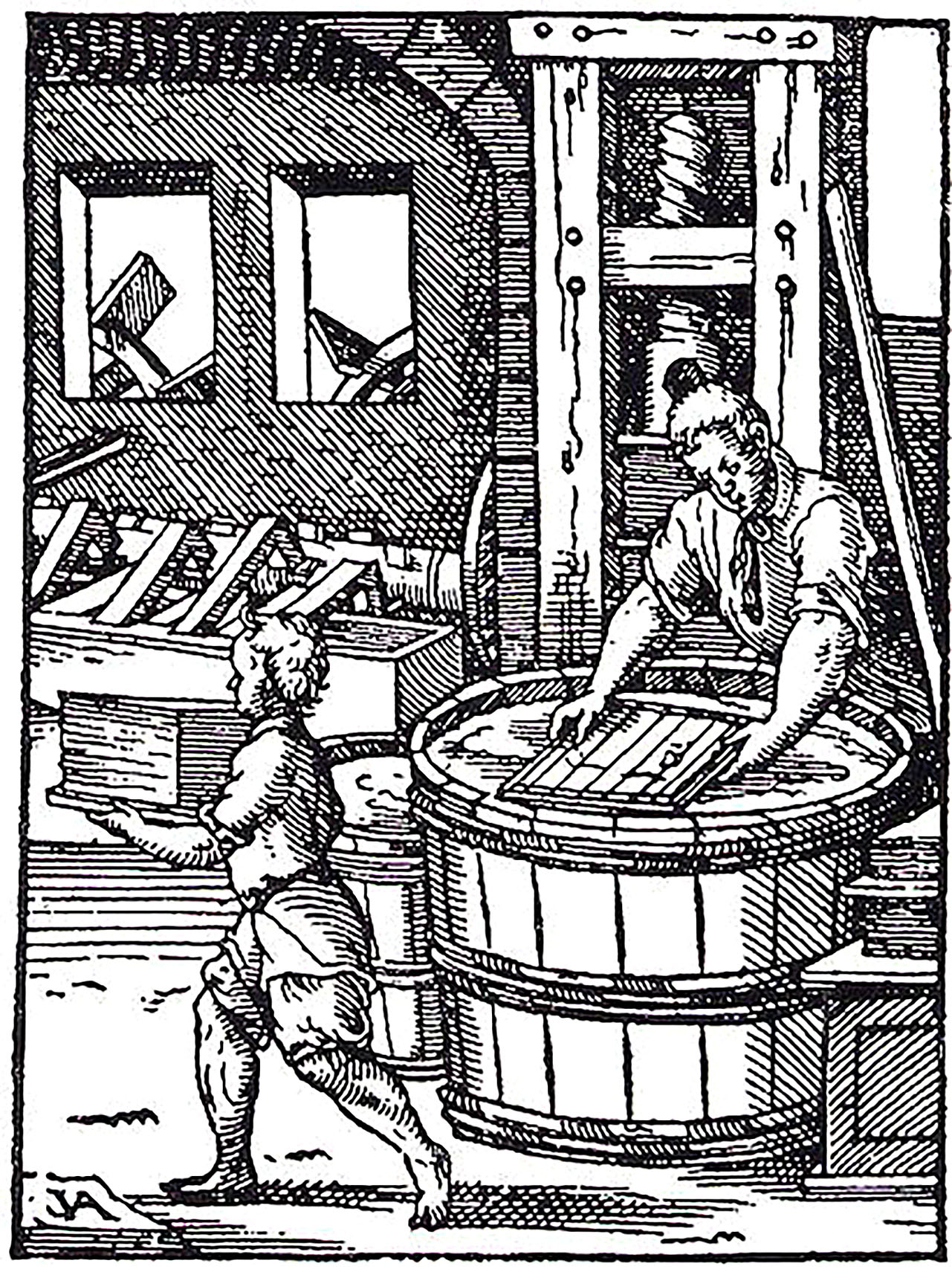

The art of papermaking has its roots in China in the 1st Century A.D. The process was first documented in 105 A.D. and ascribed to Cai Lun (Basbanes, 2014). Watermarks only appeared later, first being documented in 1282. Watermarking happens during the process of making a sheet of paper, while the paper is still wet. Watermarks are a result of changing the thickness of a specific part of the paper, creating a highlighted area – and as a result, the shadow of this area. We can track the beginning of watermarks to the town of Fabriano (Hunter, 1987). It is essential to acknowledge the historical importance of the Italian city of Fabriano. From the name Fabriano, in Latin Faber > Făbrĭcĭus, meaning craftsman, artificer, maker (Latdict, n.d.). The practical skills in forging metal and shaping wire were crucial for building the frames used to remove excess water, gather the pulp, and start forming the first sheets of paper.

Figure 06 – Papermaking (From The Book of the Trades) (Amman, 1568)

Intentions in the use of analogue watermarks

The history of watermarks is still relatively obscure. It is not possible to fully trace their original significance. A few different theories have been discussed on the actual purpose and use of these venerable imprints. One that I came across, was to help with the production of the sheets of paper. Watermarks were used to identify the size of a frame and leave an imprint in the produced output (Hunter, 1987). Another hypothesis is that the craftsmen working in the production of paper were illiterate. Watermarks were then a strategy of communicating through pictures or symbols, thus leading to a smaller chance of misunderstandings. The first applications of watermarks make these possibilities seem compelling, but it is also possible that these may have been an artistic product of the papermakers, simply a fashionable imprint left by the artists making the frames, as a way to identify themselves, as an aesthetic enhancement or a signature of quality (Watkins, 1990).

Watermarks establish provenance to manufacturers of papers, paper mills and manuscripts. Across Europe, Africa and the Middle East, their use contributed to increasing the desire for specific papers and was a critical factor in recognising paper quality. Nowadays, watermarked sheets carry bits of evidence documenting their lifespan and transactions.

It is wrong to immediately establish the provenance of a book to one particular place solely based on the watermarks, due to the commercial trade of paper. While an Italian watermark may be found in a sheet of paper, this only sets provenance to where the paper was manufactured, and not its subsequent life. Watermarks could comprise graphics such as animals, plants and sacramental imagery, but also representations of geographical territories and in general depictions of Western culture. In Umbria, Italy, for example, the Benedictine monasteries endorsed the three-peaked hill topped with a cross as their symbol. Another watermark imagery, developed by the French and Venetians, was the tre lune (three crescent moons), a strategy adopted because Muslims in the Ottoman market were expected to choose papers with these kinds of imagery rather than Christian motifs (makingmanuscriptsblog, 2017).

Figure 07 – Three-peaked hill, snake and cross (Österreichische Akademie, 1484)

Connection between watermarks and library stamps

There is an active link between watermarks and the introduction of library stamps – both creating a body of evidence when trying to establish connections in a collection. Library stamps are also perceived as an imprint left visible, sometimes glued, and making it possible to question property and acquisition. In libraries, books are stamped to declare ownership, establishing a physical relationship between the physical medium and the infrastructure. At the same time, traces of provenance are added to these collections. Library stamps do not associate a reader to a book, nor were they intended to do so: the focus is on documenting the circumstances and date of acquisition.

Though library stamps are helpful to determine the time frame and history of an item in a collection, the process of stamping a book is not necessarily performed when it enters a collection. Unlike watermarks, where it is unlikely that the act of tempering the paper fibres doesn’t occur simultaneously to when a paper sheet is made, stamps were commonly applied at a later date, after acquisition. This led to mistakes that are now widely recognised. Along with stamps, clues may be found on bindings, bookplates or inscriptions in order to build a body of evidence for determining both the circumstances and the date of acquisition (Duffy, 2013).

Figure 08 – Left: oval hand stamp for manuscripts with the words

“BRITISH LIBRARY”.

Centre: India Office hand stamp for non-small

“claim material” items. These items were treated as part of the

British Library collection.

Right: Library stamp from previous

Oriental and India Office Collections. Use of this stamp ceased on 1

September 2005 (Unknown, n.d.).

Intentions in the shift toward digital watermarks

Watermarks became more relevant with the introduction of paper currency. One of the notable shifts identified was when watermarks were first applied to banknotes in England, by a papermaker named Rice Watkins in 1697 (Mockford, 2014). Watermarks were added as a way to deter counterfeiting and to make the act of forging more difficult, thus making it easier to target forgers. In England, in 1773, forging a watermark with the name of the Bank of England was made punishable by death.

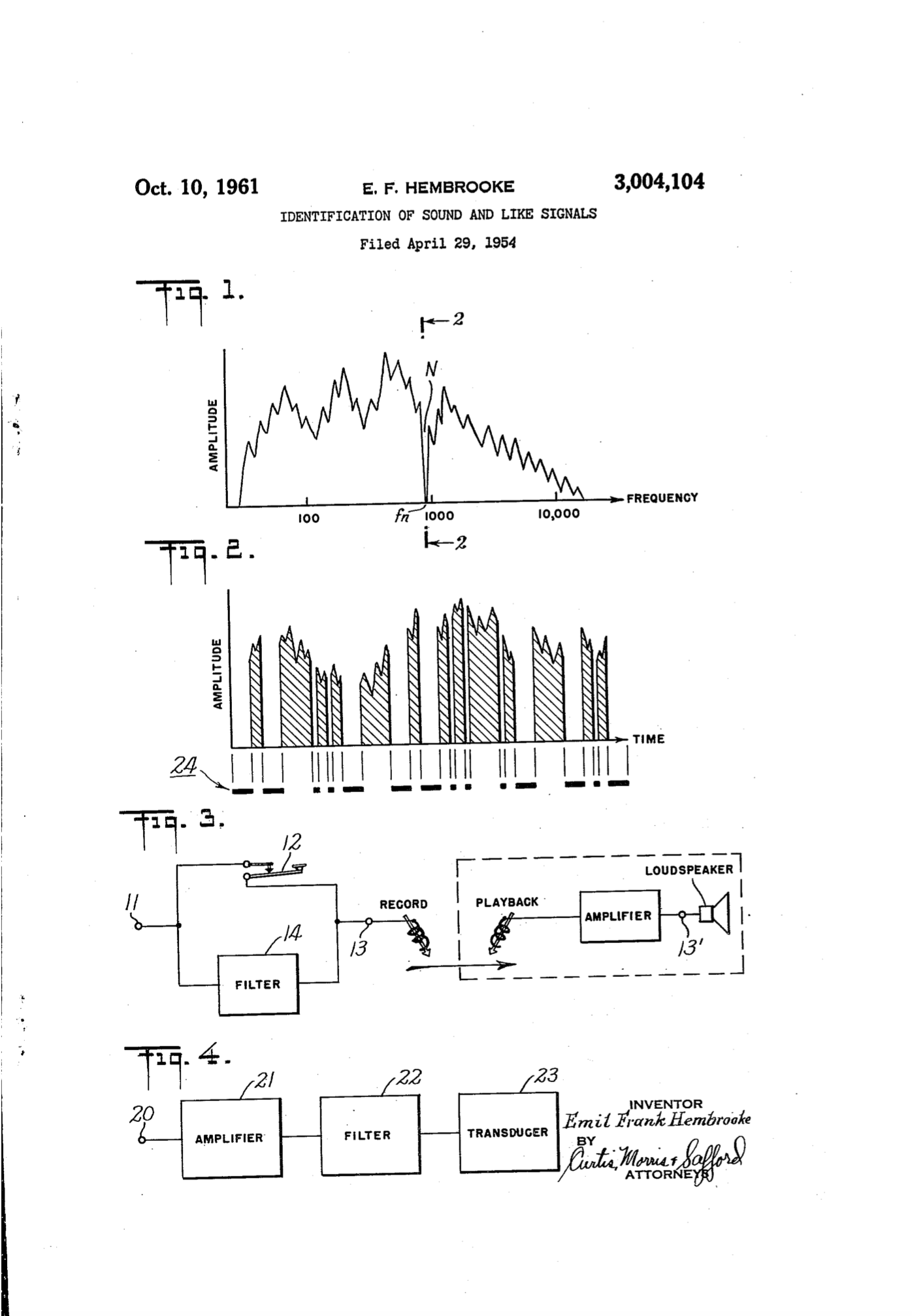

Just as with paper money, watermarks are now used to establish authenticity, and their digital implementation has become increasingly popular. Emil Hembrooke patented the first digital watermark (“Identification of Sound and Like Signals”, US Patent 3,004,104 Filed 1954, Issued 1961). In the U.S. patent, we can read: “The present invention makes possible the identification of the origin of a musical presentation and thereby constitutes an effective means of preventing such piracy” (J. Cox and L. Miller, 2002).

Figure 09 – Patent for “Identification of Sound and Like Signals” (Frank, 1954)

In the ’90s, interest in watermarks increased dramatically. Currently, one can find them in various forms of copyrighted material. As most information and data are stored in digital rather than physical formats, providing legitimacy and proving authenticity are increasingly seen as urgent tasks (Shih, 2017). Digital watermarks are mostly known as being visual. The normalisation of their use in photographs, and on video stored on DVDs, is a well-known reality by now. They also often appear in trial software. Instead of restricting the use of the software, watermarks are appended while exporting the final version of the user’s work. I read this action as an arrogant type of advertisement, and reducing users to a commodity. Instead of benefiting from software licenses, users are indefinitely broadcasting companies’ logos within their work. This technique is enforced to deter the use of trial versions and provides only one option: it forces those who need the software to buy it.

Appropriation in publishing

Another significant shift in the use of watermarks happens with their appropriation in the publishing business. Watermarks are now used to create a body of evidence on users, adding traces that relate to the subject more precisely with geolocation, IP addresses, MAC addresses, email addresses, etc. An excellent example of this phenomenon is the enforcement by the publisher Verso Books, whose books are sold in an online eBook store where a new page is appended at the beginning of each file with the downloader’s name and email address. It also watermarks the IP address of the downloader in the footer of the first page of every chapter.

During my research, I stumbled across the article Verso Books Shows That it Is Possible to Use Customer-Friendly DRM While Still Calling Customers Pirates by Nate Hoffelder, about different forms of digital rights management (DRM). In this article, the writer starts with a disclaimer in which he portrays himself as “a supporter of milder types of DRM like digital watermarks” (Hoffelder, 2014). What caught my attention was how the mode of address changes when he starts to identify all the unnecessary strategies implemented by Verso Books in their eBooks. More importantly, we can understand that their watermarks didn’t go unnoticed to the store’s users. A source interviewed states: “Personally, I felt like I was constantly being sent a stalker’s note saying, ‘I know where you live.’ It put me off reading the books entirely.” (Hoffelder, 2014). The increase of imprints that identify us as downloaders and as printers is alarming. Verso Books are calling out their users as pirates, while companies such as BooXtream (see next paragraph) are making this possible, using us as an asset upon which to capitalise.

I was able to identify the company that develops the watermarks for Verso Books: a Dutch DRM company called BooXtream®. It’s worrying to read how they portray themselves: the first quality they promote about their DRM methods is traceability. We can read in bold font: “A publication that has been BooXtreamed can be traced back to the shop and even to the individual customer.” (BooXtream, n.d.). Watermarks are now perceived as something to fear, something that makes us feel uncomfortable. Surveillance might be quickly spotted, as commonly happens with CCTV, because we can establish a physical connection with it, we can see it, we can choose a different path to walk away from it, or we can even try to disguise ourselves. We can accept that digital surveillance is a reality, but we don’t feel a close connection to it just yet. Digital watermarks might be the vehicle establishing this direct connection. It is still tricky, though, to predict what will be the impact of these techniques if users are afraid to share an eBook they have bought.

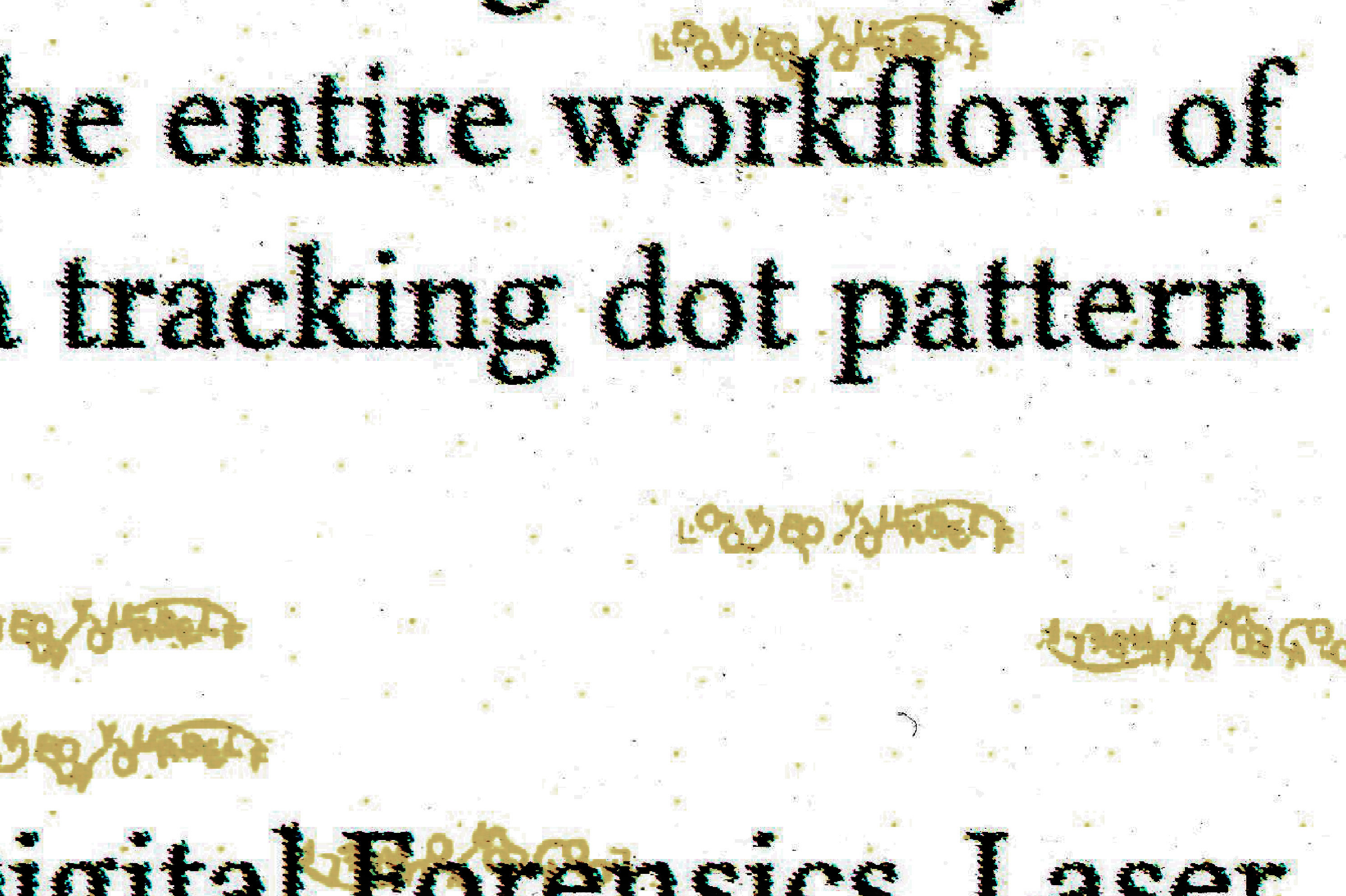

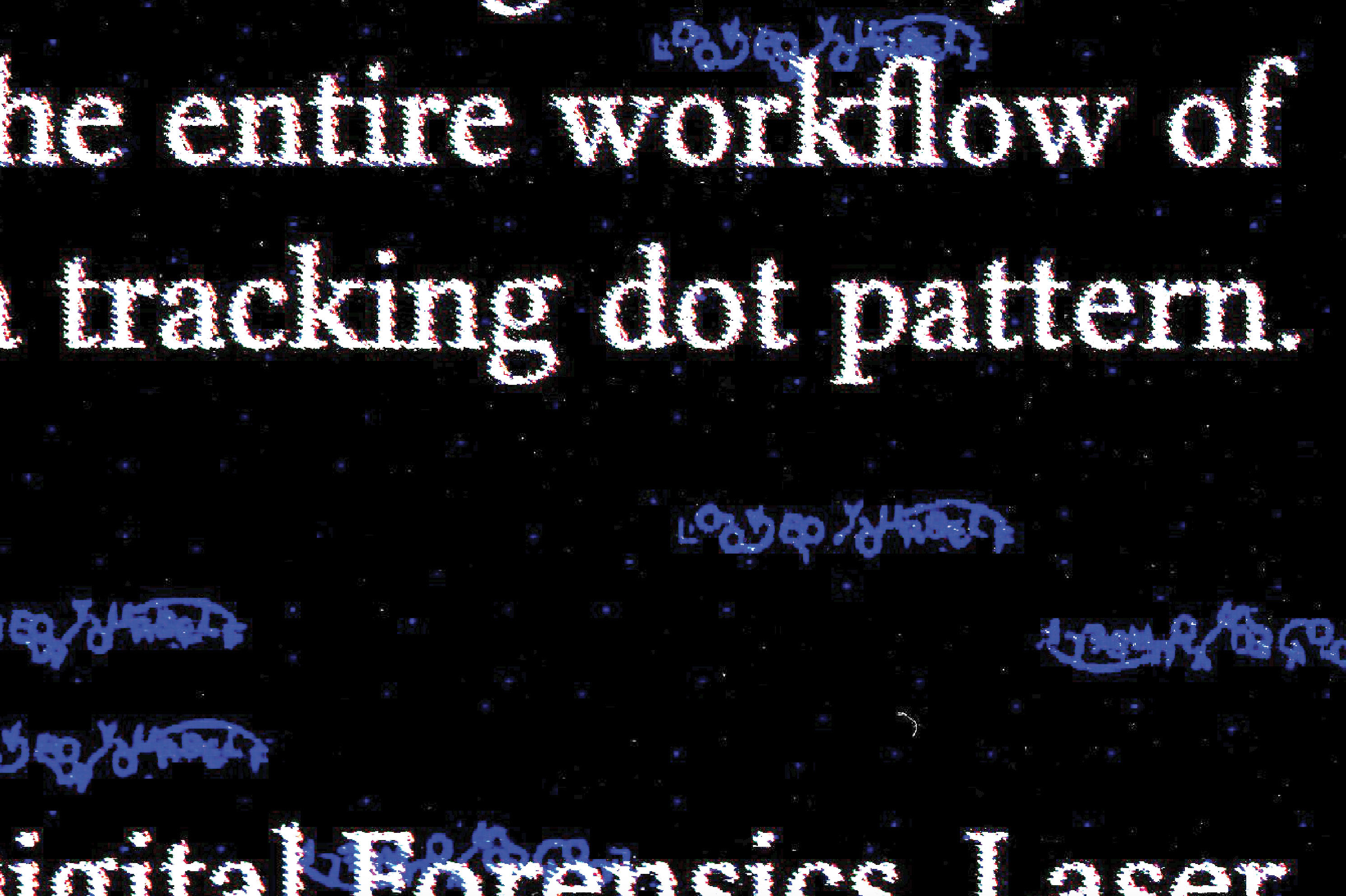

Surveillance in publishing manifests itself in ways that are not always obvious. The Electronic Frontier Foundation has published an article raising awareness of the Machine Identification Code. First described in 2004 by PC World in an article titled “Government Uses Color Laser Printer Technology to Track Documents”, this code is formed by a pattern of dots appended by the printer’s software to every printed page. These are almost imperceptible yellow dots carrying information such as the date and time of print, and the serial number of the machine. Similar technology is used when you try to scan a banknote. A sequence of printed yellow dots in the paper triggers the printer to overlay a striped pattern on the top of the copy, preventing duplication.

I tried to find out whether this code was still in use, and for this I needed to be able to prove its existence. I started by using methods to identify these invisible dots, such as UV lights, and different printers, from HP to Canon and from inkjet to laser printers. When I had almost given up, disappointed with all the time I had invested in this, I started to reverse-engineer this code and implement my own. While creating messages printed in minimal font size and scanning these printed pages, I began to understand how to make this pattern visible. With a new scanner with a resolution of 1200 dpi, and after inverting the document colours, the dots suddenly appeared. As if by magic, a mesh of my experiments and the tracking dots started to emerge. Ultimately, I was able to identify them in all the school printers in the Willem De Kooning Academy’s Blaak building. It is worrying to think that this hidden code infiltrates documents and can be seen by anyone. It’s not only used if you are suspect of a crime, but it’s available for everyone at all times. Coming across them made me rethink what it means to publish through printed media, how safe it actually is, and how it affects those who depend on these forms of publishing.

Figure 10 – Tracking dots found in the university’s printers (Sá Couto, 2019)

In this second chapter, I have explored the progression of watermarks. From their background, until their appropriation, as an asset to incite fear and self-awareness, and to remotely control and constrain user actions. It was essential for the development of my project to emphasise the current value of ancient watermarks.

In the next chapter, I will expand my research, starting from the point of view that the early framework of watermarks is something I consider necessary to resurface. I wish to demonstrate that what lies at the heart of their use is the ability to portray crucial interrupted actions and moments in history, granting insights into hidden processes of fabrication, documented in the sheets of paper. And at the same time, carrying clues to comprehend their artisans, the historical timeframes, and different imagery. I will then expand on the use of digital watermarks, apart from what I recognise as their misappropriation, exploring how the current attitude towards digital watermarking is not the only valid one. I have focused my research on how the discourse around these reinforcements of copyright can be flipped around. I will delve into tactics that seem mainly negative, and re-reappropriate them.

Part 3 – Watermarks operate in different roles

Introduction to my creative response

My project, Tactical Watermarks, is an online republishing platform. I actively make use of digital watermarks as a means to explore topics such as anonymity, paywalls, archives, and provenance. I describe ways of living within and displaying resistance against a culture of surveillance in publishing. This is relevant in order to understand and explore what it means to live in a culture of constant tracking, rather than aiming to solve the many problems of surveillance.

With this platform, users can upload and request different titles. While talking with enthusiasts from the Library Genesis forum, I understood the need to create a tool that allows people to share watermarked PDFs in a safe way. My platform is not a library, nor is it an archive. I don’t keep the files, nor do I intend to archive them. What I will be doing, is opening a space to de-watermark files, and to append new anonymous watermarks with the technical and personal concerns of sharing specific texts. In the end, these stories will circulate alongside the main narrative. This is an automated republishing stream that enables me to spread the produced files to different libraries, from aaaaarg.fail to Library Genesis.

My use of watermarks, and more specifically my creative response, has the primary objective of creating a positive discourse around the act of watermarking. This discourse will enable the creation of a top layer of information, able to embed traces of provenance in different texts. By provenance, I intend to express specific trails – not those used to surveil users, but all those that make it possible to trace historical importance to files, and that facilitate precise documentation within an archive or library. Though Tactical Watermarks is not only a theoretical system, I will also delve into how it can be deployed, comparing it to other projects or approaches that I have encountered, and reflect upon their influence in my own practice.

I wanted to challenge centralised distribution channels, and wondered how the process of adding “stains” can be twisted and revived. “Stains” are how I call user patches or marks that are difficult to remove and that do not play an active role in archives. While exploring the process of adding imprints, different uses arose: as a way to obscure previous uses, to comment on the situation, to encourage behaviours, to create relations and communities, to increase the sense of solidarity in archives, to generate digital enhancements and marks of quality, etc.

I aim to link my creative response to what has been happening in parallel within different cultures, from graffiti culture to other controversial artistic practices. Watermarks may form a discourse around topics such as anonymity, borders, archives, and provenance. While rethinking watermarks, I explore their hidden layers and their aspects of surprise, visibility or invisibility, within different forms of communication. It is essential to acknowledge that watermarks have the power to infiltrate, to perform different roles and to create parallel streams of information within various texts. When it comes to publishing, how can watermarks generate a critical discourse around the right to access knowledge, and represent those who fight for this right?

1 – Displaying the provenance of a medium

I will start by consolidating how I use the term “provenance”. By provenance, I unify all processes that provide clues and evidence as to the origin of a file, until the moment it enters a collection. These traces may identify the source of a text, its place of origin, or even the motivations behind why an individual made it public. All these voices will be unified as part of a stream of empathy, decisions, hidden tasks, and actions.

The flow of texts, downloads, and users is always constrained by the politics of platforms that grant access and disseminate the materials. Different platforms share the same documents and versions of a file. With Tactical Watermarks, I aim to document this hidden activity and make it visible. With watermarks, and without compromising the identities of users, I aim to set ground to what I find noteworthy – such as finding ways to translate the movement of users and texts, within this complex mesh. To achieve this, I aim to materialise the tasks hidden behind the process of uploading a file to a digital space (these actions may require processes such as digitising) – or even the motivations behind the selection.

2 – Signatures

In Tactical Watermarks, I also propose that digital watermarking may be used as a signature, as in graffiti culture or software crack intros.

Just like distributing copyrighted material and cracking software, graffiti is controversial. It has a rich background dating back to various cultures including ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, where writing or drawing on walls or other surfaces was common. Graffiti is seen as a form of artistic expression without permission. Simultaneously, in software crack intros, we can discover pseudonyms used to protect identities and thwart prosecution; in graffiti, a subculture of challenging authority, the same thing happens.

In software crack intros, such signatures (referred to as “crack screens”) were customarily included within the in-game title screens that display the title of the game, the logo of the producer, and a graphic providing the player with a glimpse of the theme of the game. Crack intros appeared for the first time in the ’80s and were not commissioned for a commercial purpose. Instead, these were introduced by a programmer or a group of coders, graphic artists, and musicians that were responsible for removing the software’s copy protection and making the crack public (Green, 1995). The signatures were initially simple statements, such as “cracked by...”, sometimes intentionally misspelt as “kracked by...” (Reunanen et al., 2015). While crack intros are in many ways similar to graffiti, crack intros invaded the private sphere rather than the public space (Cubitt and Thomas, 2009).

A link between these forms of signatures and watermarks is found in their ancient imagery. Craftsmen would explore pseudonyms – in this case, in the form of pictograms built in the paper frames. These forms of anonymity open a path to explore digital watermarking as an arrogant way of identifying users as liable for the processes and decisions behind releasing a file into the public sphere, without carrying any liability whatsoever. Tactics such as using pseudonyms will be reappropriated to challenge authority, digital identity and accountability.

3 – Watermarks to obscure

Tactical Watermarks is not only about revealing hidden layers and augmenting the memory of an archive. It is also about creating strategies to suppress unwanted information. It is valuable to stress that in the contemporary panorama of digital watermarking, calling out a user identity is the ultimate goal. While recognising the intention to remove this layer of information, it is relevant to create a parallel to the project SecureDrop. This project was first released under the name DeadDrop, designed and developed by Aaron Swartz and Kevin Poulsen. SecureDrop is a free software platform that enables safe communication between whistleblowers, journalists and different organisations. In this platform, whistleblowers, which are the sources, submit documents and data while avoiding most common forms of online tracking (Ball, 2014). During this process, sources are also assigned a random username, allowing a journalist to contact and privately chat with them.

The main intention of both my project and SecureDrop is the creation of strategies to anonymously disseminate files not intended to be part of the public sphere. Both facilitate a place where users anonymise data; SecureDrop mostly deals with private or public organisations trying to protect secrets, and as a response to whistleblowers trying to expose these same secrets. Tactical Watermarks will deal with publishers protecting copyrighted materials and readers seeking to share these with their peers. In SecureDrop, this happens by using private, isolated servers, as well as encryption and decryption tools. In Tactical Watermarks, this is done by using watermarks as a way to obscure already existing imprints aimed at making users accountable, overlaying new ones, and re-writing new subjective metadata to documents.

4 – As a means of expression

Within this framework, through the act of watermarking, I will create a space to publish undercovered personal, political and other kinds of messages. With my creative response, I consider users commenting and publishing their thoughts disseminated person-to-person with the actual circulation of a file as relevant. Having the power of saying that I am here, and that I disagree with how paywalls, borders and rules are structured and reinforced is compelling and pertinent. These messages must be public.

Commenting as a strategy of contemporary political resistance also happens in cracked software, such as Adobe Zii (or Adobe Zii Patcher), a one-click software program patcher or activation tool for Mac. The developers of this software inserted the quote “why join the navy if you can be a pirate” which is displayed during the actual process of patching the desired software. It is striking how this discourse differs from the one seen in crack intros – commenting on a situation and encouraging provocative behaviours. The reference is established through the act of patching, rather than exposing the individuals behind it.

Watermarks will be used to reflect upon power structures, and to disseminate beliefs related to struggles within free access to knowledge and information. By infiltrating new digital watermarks, we are not only able to reach those who are already fighting within this culture, but also those who might be uninformed users of shadow libraries and alternative publishing streams.

5 – Creating relations and communities

In the first chapter of this thesis, I explored how different media are used to bypass surveillance and to publish within alternative streams of access. This used to happen through zines, the underground press, or other types of publishing such as samizdat. Currently, parallel publishing streams exist mainly in the form of digital online platforms, maintained to make public all sorts of copyrighted and forbidden material. Within the context of Tactical Watermarks, it seems relevant to delve further into strategies that facilitate communication, especially the use of steganography.

Even though several forms of communication responsible for avoiding conventional methods of surveillance are mainly achieved by writing encoded messages and using decoding systems when the message reaches its target, with steganography this happens differently. The main strategy is to hide the message in plain sight. Steganography allows two parties to broadcast a message hidden or disguised as other data. Watermarks and steganography both happen in digital and analogue formats. While both terms can be applied to the transmission of information hidden or embedded in other data, they are often wrongly merged and it is vital to clarify them. Steganography relates to undercover point-to-point communication between two parties. Watermarking has the extra requirement of robustness towards potential attacks (Katzenbeisser and Petitcolas, 2000).

Steganography is a subdiscipline of information hiding. In Amy Suo Wu’s book A Cookbook of Invisible Writing, alternative forms of communication are presented in the format of recipes, documenting techniques borrowed from spies to prisoners, but not only old tactics of steganography exist. In China, researchers have understood that while digital communications and data security are becoming more sophisticated, there is still a need to develop ways of sending hard copy messages securely. Scientists developed a printing technology which can only be read by shining a UV light over the printed medium (Davis, 2019).

All these techniques of communication have led me to explore which strategies we can reappropriate using watermarks as a way of annotation. How can we open space for communication between users of a system while maintaining their anonymity? One might have felt the thrill when a downloaded file from Libgen or similar library still contains traces of previous users. Relating, through such traces, to someone we don’t know can be quite amusing. You feel part of a movement, as you have had a glimpse of a moment, captured in time.

With Tactical Watermarks, I will open a space for dialogue, as well as demonstrations of solidarity. I do not plan to make this something you may find by chance; I aim to explore the possibilities of making someone thrilled to see these messages as a compulsory or a regular habit.

6 – Sensorial augmentation

Finally, digital watermarks still have space to produce sensorial enhancements. Enacted through watermarking and with a background in the practice of graphic design, I reckon that we can establish different rhythms and hierarchies within a narrative. As introduced earlier in this text, watermarks might have had their origin in manufacturing processes, or may just as well have been a form of artistic expression by papermakers. Within Tactical Watermarks, digital watermarks may substitute the impact that graphic design has in the process of creating books as a physical medium, where they can be recognised as an object by themselves. In graphic design, choices such as the paper, the binding, or even how different chapters are separated become part of an endeavour to heighten the narrative. Mixed attitudes exist in this process, either by trying to respect the narrative, without overpowering it, but also, as a way of exploring it as a medium where restructuring may form new ways of reading. Two constants are then present: the exploration of repetition, its absence, and the experimentation regarding reading flows.

The main drive during this research has been to explore how analogue techniques can be appropriated and transported into digital watermarking. I find unconventional strategies, such as the use of scented paper in print, to be particularly amusing. Such methods allow us to rethink the flow of information and to take part in shaping the perception we have of texts. Through this scented technology, we explore vision and scent at the same time, transporting us to different realities, creating a stimulus that we don’t usually experience while reading. In digital files, I compare this to the feeling of encountering graphic elements that exist outside the main narrative. While most digital files lack personality, by appending new visual elements, I aim to incite new sensations while building new experiences through paratextual components.

Conclusion

Delving into tactics enforced by organisations that close access to published material might have been discouraging. But it wasn’t. While companies are investing money to protect their sources of income, it’s exciting to feel that volunteers continue to be motivated to create reactive measures against closed access publishing. Throughout this text, I have unpacked the reactions regarding digital surveillance and the motivations behind these countermeasures. Every time we make use of such projects, they seem like finished products, where no effort from our side is necessary to make them work. This thesis aimed to create a space to introduce some of the platforms, tools, and users that contribute and exist behind projects that make access widely available.

My project, Tactical Watermarks, is motivated by all the invisible individuals behind alternative publishing platforms – from curators, to those who host, upload and even download material. With my creative response, I intended to create one more tactic to bypass surveillance in the publishing realm. However, my response does not claim to be the foolproof answer in opening access to published material. It is reassuring to feel that a wide variety of infrastructures, from shadow libraries to online digital archives, already exist as temporary solutions to the main problem. It is also comforting that users display daily acts of voluntary resistance amongst themselves – from researchers creating informal groups to share copyrighted material, to users “mirroring” collections in attempts to extend their lifespan. My project initially focused on acknowledging the importance of informal communities of resistance, and on the individuals that make this resistance possible. Tactical Watermarks reflects upon the social, political and cultural aspects behind the use of restrictive measures in publishing. It is not a finished project, nor does it intend to be; rather, it embraces the fact that the possibilities of tactical watermarks will continue to reveal themselves through extensive use of the tool.

Researchers need to react against organisations creating monopolies and closing access to published material. We need to build new online spaces where people can connect. Users need access to online forums where counterstrategies are widely available. We need to organise workshops and build communities to bypass the control of corporations that are focused only on the monetary outcome of research. It’s important to continue sharing texts and opening access to our resources collectively. We need to mirror collections and to produce new and unpredictable reactive actions against closed publishing streams. When it comes to opening access to paywalled material, much is yet to be done. Tactical Watermarks is a way to stimulate new reactive measures, embracing a positive discourse in terms of subverting digital surveillance.

References

-

Balázs, B. (2018) “Library Genesis in Numbers: Mapping the Underground Flow of Knowledge”. Shadow Libraries: Access to Educational Materials in Global Higher Education. Ottawa : International Development Research Centre: The MIT Press.

-

Ball, J. (2014) “Guardian launches SecureDrop system for whistleblowers to share files”. The Guardian, 5 June 2014. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/jun/05/guardian-launches-securedrop-whistleblowers-documents (Accessed: 24 October 2019).

-

Basbanes, N .A. (2014) On Paper: the Everything of Its Two-Thousand-Year History. New York: Vintage Books.

-

BooXtream (2019) “BooXtream: Social DRM To The Max”. Available at: http://www.booxtream.com/ (Accessed: 2 March 2020).

-

Bukovskiĭ, V. K. (1988) To Build a Castle: My Life as a Dissenter. Washington, D.C.: Ethics and Public Policy Center.

-

Cubitt, S. and Thomas, P. (2009) Re:live Media Art Histories 2009 Conference Proceedings. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne & Victorian College of the Arts and Music.

-

Custodians (2015) “In Solidarity with Library Genesis and Sci-hub”. Available at: http://custodians.online/ (Accessed: 7 February 2020).

-

Davis, N. (2019) “Scientists Invent New Technology to Print Invisible Messages.” The Guardian, 25 September 2019. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/sep/25/scientists-invent-new-technology-to-print-invisible-messages (Accessed: 30 October 2019).

-

Duffy, C. (2013) “A Guide to British Library Book Stamps: Collection Care blog”. Available at: https://blogs.bl.uk/collectioncare/2013/09/a-guide-to-british-library-book-stamps.html (Accessed: 12 October 2019).

-

Duncombe, S. (2017) Notes from Underground Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture; with a new afterword: Do zines still matter? Portland, Or.: Microcosm Publishing.

-

Green, D. (1995) “Demo or Die!” Wired, 1 July. Available at: https://www.wired.com/1995/07/democoders/ (Accessed: 10 January 2020).

-

Grundhauser, E. (2015) “Soviet Scenesters Used X-Rays to Record Their Rock and Roll”. Available at: http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/soviet-scenesters-used-xrays-to-record-their-rock-and-roll (Accessed: 30 January 2020).

-

Hoffelder, N. (2014) “Verso Books Shows That It Is Possible to Use Customer-Friendly DRM While Still Calling Customers Pirates”. Available at: https://the-digital-reader.com/2014/06/07/verso-books-shows-possible-use-customer-friendly-drm-still-calling-customers-pirates/ (Accessed: 17 November 2019).

-

Hunter, D. (1987) Papermaking: the History and Technique of an Ancient Craft. New York: Dover.

-

Miller, M. and Cox, I. (2002) “The First 50 Years of Electronic Watermarking”. EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing. doi:10.1155/S1110865702000525.

-

Kalathil, S. and Boas, T. (2001) “The Internet and State Control in Authoritarian Regimes: China, Cuba, and the Counterrevolution”. First Monday, 6. doi:10.5210/fm.v6i8.876.

-

Katzenbeisser, S. and Petitcolas, F. A. P. (2000) Information Hiding Techniques for Steganography and Digital Watermarking. Boston: Artech House.

-

Kind-Kovács, F. and Labov, J. (2015) Samizdat, Tamizdat, and Beyond: Transnational Media During and After Socialism. New York: Berghahn Books.

-

Kirkpatrick, D. (2012) The Facebook Effect: The Real Inside Story of Mark Zuckerberg and the World’s Fastest Growing Company. London: Virgin Digital.

-

Latdict (n.d.) “Latin Definition for: faber, fabri” (ID: 20146). Available at: https://latin-dictionary.net/definition/20146/faber-fabri (Accessed: 25 November 2019).

-

Lessig, L. (2008) Code: And Other Laws of Cyberspace, Version 2.0. New York: Basic Books. Available at: https://www.worldcat.org/title/code-and-other-laws-of-cyberspace-version-20/oclc/1109503030&referer=brief_results (Downloaded: 3 February 2020).

-

makingmanuscriptsblog (2017) “Watermarks! Making Manuscripts in the Medieval and Early Modern World”. Available at: https://makingmanuscriptsblog.wordpress.com/2017/10/02/watermarks/ (Accessed: 11 December 2019).

-

Mann, S. (2003) “Existential Technology: Wearable Computing Is Not the Real Issue!” Leonardo, 36 (1): pp. 19-25.

-

MayDay Rooms (n.d.) “MayDay Rooms: About”. Available at: https://maydayrooms.org/ (Accessed: 13 November 2019).

-

Metahaven (2013) Can Jokes Bring Down Governments?: Memes, Design and Politics. Moscow: Strekla Press.

-

Miles, B. (2016) “The Underground Press”. Available at: https://www.bl.uk/20th-century-literature/articles/the-underground-press (Accessed: 31 October 2019).

-

Mockford, J. (2014) “‘They Are Exactly as Banknotes Are’: Perceptions and Technologies of Bank Note Forgery During the Bank Restriction Period”, 1797-1821. Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/001e/004f8e526855afe09fcb674b8ba1d9cd602f.pdf.

-

Munster, A. (2011) Materializing New Media: Embodiment in Information Aesthetics. Lebanon: Dartmouth College Press. Available at: http://grail.eblib.com.au/patron/FullRecord.aspx?p=1085079 (Downloaded: 19 November 2019).

-

Reunanen, M., Wasiak, P. and Botz, D. (2015) “Crack Intros: Piracy, Creativity, and Communication.” International Journal of Communication, pp. 798-817.

-

Schroeder, R. (2018) “The Internet in Theory”. Social Theory After the Internet: Media, Technology, and Globalization. UCL Press. pp. 1-27. doi:10.2307/j.ctt20krxdr.4.

-

Shih, F. Y. (2017) Digital Watermarking and Steganography: Fundamentals and Techniques. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, CRC Press. Available at: http://www.crcnetbase.com/isbn/9781498738767 (Downloaded: 25 November 2019).

-

Smith, M. and Freer, B. (2012) “The POW WOW Newspaper”. Available at: http://www.merkki.com/powwow.htm (Accessed: 9 February 2020).

-

Watkins, S. (1990) “Chemical Watermarking of Paper”. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, 29 (2): pp. 117-131. doi:10.2307/3179578.

-

Wu, A. S. (2019) A Cookbook of Invisible Writing. Eindhoven: Onomatopee.

Images

-

Figure 01. Unknown. (n.d.) Bone Record [Photograph]. Available from: http://www.movietrainer.com/movies/film/roentgenizdat-the-strange-story-of-soviet-music-on-the-bone/2016 (Accessed: 31 October 2019).

-

Figure 02. Kuptsow. (1944) D-Day - June 6, 1944 - Front [Scan]. Available from: http://www.merkki.com/powwow.htm (Accessed: 8 May 2020)

-

Figure 03. russelgz. (n.d.) Horse grass mud [Photograph]. Available from: https://m.24sata.hr/junior/cupave-alpake-bolje-da-ju-ne-ljutite-jer-ce-vas-pljunuti-352136 (Accessed: 8 May 2020)

-

Figure 04. Steiner, P. (1993) On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog [Cartoon]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/comic-riffs/post/nobody-knows-youre-a-dog-as-iconic-internet-cartoon-turns-20-creator-peter-steiner-knows-the-joke-rings-as-relevant-as-ever/2013/07/31/73372600-f98d-11e2-8e84-c56731a202fb_blog.html (Accessed: 8 May 2020).

-

Figure 05. Unknown. (2019) Cover picture: Ask for PDFs from People with Institutional Access [Screenshot by author]. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=10104619526528602&set=p.10104619526528602 (Accessed: 8 May 2020).

-

Figure 06. Amman, J. (1568) Papermaking (From the Book of the Trades) [Illustration]. Available from: https://www.wga.hu/art/a/amman/amman1.jpg (Accessed: 8 May 2020).

-

Figure 07. Österreichische Akademie. ( 1484) 3 Mountain Hill, Snake and Cross [Scan]. Available from: http://www.ksbm.oeaw.ac.at/_scripts/php/BR.php (Accessed: 8 May 2020).

-

Figure 08. Unknown. (n.d.) Left: Oval hand stamp for manuscripts with the words BRITISH LIBRARY. Centre: India Office hand stamp for non-small “claim material” items. These items were treated as part of the British Library collection. Right: Library stamp from previous Oriental and India Office Collections. Use of this stamp ceased on 1 September 2005 [Scan]. Available from: https://blogs.bl.uk/collectioncare/2013/09/a-guide-to-british-library-book-stamps.html (Accessed: 31 October 2019).

-

Figure 09. Emil Frank, H. (1954) Identification of sound and like signals [Patent]. Available from: https://patents.google.com/patent/US3004104 (Accessed: 31 October 2019).

-

Figure 10. Sá Couto, P. M. (2019) Tracking Dots found in the university printers [Scan]. Available from: https://pzwiki.wdka.nl/mediadesign/User:Pedro_S%C3%A1_Couto/MIC (Accessed: 31 October 2019).[]{#colophon .anchor}