My Country Is Still a Colony

Introduction

According to a report by the OECD, South Koreans work the longest hours in Asia. Employees in South Korea worked an average of 2,069 hours in 2016, compared to the OECD average of 1,763 hours (Nam, 2018). I still remember a period in my childhood when my dad had to get up at 6:00 every morning to go to work in a neighbouring city of my hometown. Most of the time he came back around 8:00 in the evening, and I had to massage his back and hands to relieve his fatigue. While he was out working, I often spent time playing computer games called “Crazy Arcade” on the Korean social media platform “Cyworld” (the equivalent of Facebook in Korea, but five years older), or chatting with friends via a messenger platform called “SayClub”. For me, ever since I was young, using a computer and accessing the Internet came as naturally as playing.

Among countries that have high-speed Internet, Korea has become one of the fastest and most prevalent Internet distributors in the world (Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning [MSIP], 2017). During its development, many Korean companies started making use of the Internet as a profitable space by strategically mining data from the online activities of users. These online activities can be defined as simply browsing the Internet and being active in social networking sites, microblogs, or content-sharing sites related to leisure activities (Fuchs and Sevignani, 2013). In this way, users automatically contribute to the profitability of companies in the digital space. In other words: digital labour. This type of labour has the potential to produce a lucrative outcome in the form of data that can be unwittingly extracted for the benefit of someone else’s business interests. Users become digital workers of companies who make use of their labour to extract data. This relationship between companies and users is inequitable, and feels exploitative and unfair. Interestingly, all of these situations show similarities to historical Japanese colonialism in Korea.

As a Korean millennial who has experienced Korean work culture and digital society, I will be emphasizing here what was inherited in Korean work culture from Japanese colonialism in Korea, and my discovery of how this has been transformed to the Korean digital space. Part 1 of this essay explores why Koreans work overtime, by highlighting the history of South Korea. Part 2, “The extent of the history”, examines those aspects of work culture in Korean colonial times that have been inherited by the digital sphere. By unpacking the findings of parts 1 and 2 – free digital labour is produced based on digital colonialism – I will suggest in part 3 how we can make this palpable. In doing so, this essay attempts to scrutinise the different modes of historical and modern colonialism, and to create a sense of urgency so that everyone can become more palpably aware of the problem of free digital labour.

Part 1. How did free labour arise in its cultural context?

Why do Koreans work overtime, even young kids? In order to understand why, we need to consider work culture and work customs in the context of South Korea. More specifically, how does this affect the issue of free digital labour in Korean work culture?

1.1 Korean work ethics

The traditional way of working

In the past, the oldest communal labouring custom in Korean agricultural society was called “pumasi” (품앗이), a combination of the words “pum” which means working, and “asi” which means repayment.

Fig. 1. Pumasi in Korea.

Pumasi consisted of working together for the benefit of the community, without taking into account the value of each other’s labour contribution (Kim, 1995). This form of voluntary work allows neighbours to gather together to achieve a common goal (Kim, 1992). It emphasises the positive side of a give-and-take relationship, where people don’t make an official contract to precisely define a 50:50 relationship. Here we can also refer to a Korean human affective concept called Jeong (정), an emotional and psychological bond that joins Koreans. Jeong is considered as a kind of unique love: you can help someone without asking for compensation, giving more than you promised, because you are emotionally attached to the person you are helping (Samson, 2018).

Additionally, a piece of music would be sung while conducting a task in order to work more effectively, a phenomenon known as No-Dong-Yo (노동요). The concept of No-Dong-Yo is to work together with a certain rhythm of labour, but also to work together with little effort (Kang, 2005). It is sung in order to keep the unity of working behaviour and to work more efficiently. In this sense, the old work culture in Korea was about helping each other, and working together productively.

The reality of modern work culture

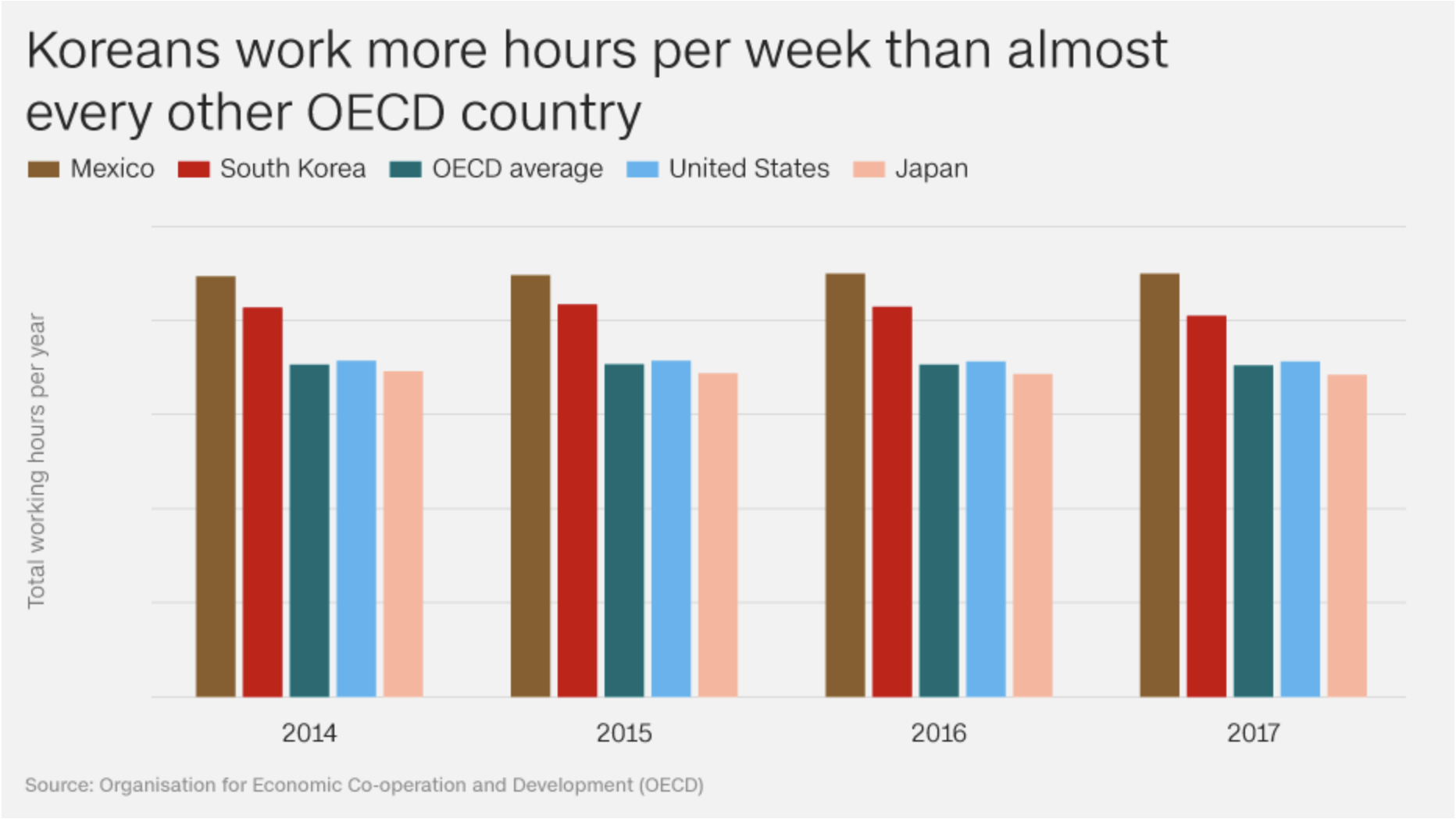

In contrast to the traditional work culture, where hard work was a positive activity for helping each other, modern Korean work culture is a negative factor in modern society. According to the newspaper The Korea Herald, South Koreans are known as the world’s second worst workaholics, ranking second in an OECD report in terms of working hours in 2014 (OECD, 2014). The average South Korean worked 2,163 hours in 2014: 271 days per year at an average of 8 hours a day. However, many companies encourage employees to work from 8:30 to 19:30, therefore the actual working hours a day are comparably longer than in other countries.

Fig. 2. Koreans work more hours per week than almost every other OECD country.

Also, many workers work overtime hours in the evening, so that they tend to stay at work until early in the morning. Nonetheless, they earn below-average wages compared to other nations in the same job group. This also applies to Korean children, who have to improve their performance by studying long hours. Based on research by the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Korean students study more than 60 hours per week, the longest amount of hours in the OECD rating (Kim, 2017). From the age of 7 until high school, students attend school from 8:30 to 18:00. Then they take extra private lessons, called Hag-Won (학원), until approximately 22:00 (Kasulis, 2017).

Confucianism, age hierarchy, compulsory culture

There are a few reasons why Koreans work so hard at school and work. In general, Korean society stems from a culture of age hierarchy in which older people get more respect, are treated better, earn more money and receive more recognition. The Five Relationships (오륜) are an important concept of Confucianism in Korea: the basic moral guidelines of how to treat people around you. Among the five relationships, there is a relationship that is related to Korean age hierarchy culture: Jang-Yu-Yu-Seo (장유유서) – old and young have an order, a hierarchy. This relationship stresses that there should be an order between younger and older because the older ones have more wisdom through their experience.

Based on Confucianism in Korea, age matters much more than ability if two people have similar skills and experience. If you’ve freshly started working in a company and you are the youngest one in the group, you will be the one who always serves morning coffee to the other team members. This can be seen between family members as well, through the principle of “filial piety” which is a virtue of respect for one’s parents, elders, and ancestors. Through this concept, a young person needs to be good to an old one, and can’t talk back to older individuals.

Another reason why Koreans work hard is derived from a compulsory work culture. There are several types of compulsory work-related behaviour in Korea, one of which is a Korean drinking culture called Hoe-Sik (회식) which literally means “a dinner with co-workers”. The gatherings often include heavy drinking as well as stays at karaoke bars, where colleagues are expected to entertain higher-positioned colleagues such as their seniors. Employees pour So-Ju, a Korean vodka, into a big beer cup and pressure their subordinates to drink (Park, 2017). This working and drinking culture contribute to what is known as Gwa-Ro-Sa (과로사): death by overworking for a company. In 2019, 457 people died due to of Gwa-Ro-Sa, which means that more than one person passed away every day from overtime work and work-related stress (Ryu, 2019). We can thus conclude that South Korea’s work culture is notorious for its rigid hierarchy, compulsory requirements, obedience, loyalty, and extreme working hours (Park, 2017).

Fig. 3. Hoe-Sik culture in South Korea.

Looking through the history of Korean work culture, the traditional way of working based on the Korean concepts of Jeong (정) and No-Dong-Yo (노동요) was about helping each other, working together to reduce the overload of work in a productive way. In contrast, age hierarchy and compulsory work culture in modern Korea make workers work longer hours, which introduces detrimental factors in their life, leading to mental issues such as depression and suicide, which I will examine later in this text.

1.2 Overwork culture in Japanese colonial times and the military regime period

Where does the hierarchical and compulsory culture, that makes Koreans such hard workers, originate from? To understand this, we need to go back to the history of South Korea in the early 20th century. Between 1905 and 1945, Korea was colonised by Japan. After the colonisation, there was a period of military rule from 1961 onward. In this section, I will present an overview of the culture that was inherited from this part of Korean history and that affected modern Korean work culture.

Japanese colonial times

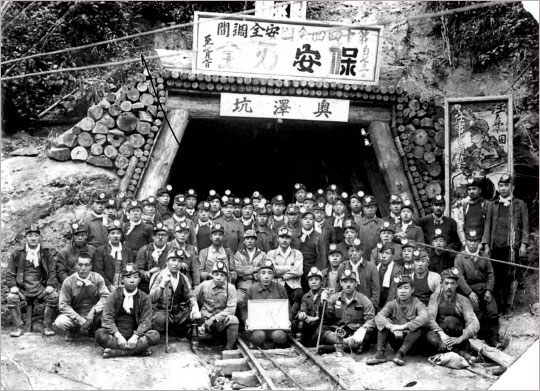

The Japanese occupiers introduced national mobilisation laws (국가총동원법) which regulated free Korean labour, including labour mobilisation (노동유통), conscription (군징병), and the use of military “comfort women” (군위안부) (Lee, 2017). Labour mobilisation refers to the allocation of manpower to industrial sites such as mines, ports, construction sites, military factories, and farms. In the mid 1920s, between 120,000 and 180,000 Koreans were forcibly transferred to Japan every year, as slaves. The range of their work was diverse, from railway construction and land expansion to coal mining, and their average working hours were more than 17 hours a day, with physical violence and no break time.

Conscription was compulsory enlistment in the armed forces: a huge group of Korean solders were forced to participate the Asia-Pacific War (태평양전쟁) during World War II to support Japan. During the war, more than 75% of forced conscription forces were Korean (Jung, 2019). According to a survivor who appeared in a TV programme in 2015: “I thought there was a coal mine, but I lived in a prison without bars” (Lee, 2017).

Fig. 4. Young people in Hong-Seong, where they were forced to work for Japan in 1934.

Fig. 5. A group of “comfort women” surviving at the Songsan comfort station in September 1944.

Besides labour mobilisation and conscription, the use of military “comfort women” was an extreme example of forced female labour and gender hierarchy, in which Korean women were forced to perform physical labour as sex slaves for the Japanese army before and during World War II (Argibay, 2003). During this period, when women occupied the lowest hierarchical level in society, between 100,000 and 200,000 Korean girls and women were deceitfully recruited, coerced or kidnapped. The Japanese occupiers recruited married women, single women, and even young girls by deceiving them into thinking they would find a new job that would enable them to support themselves. According to Lee Ok-Seon, later interviewed at a shelter for former sex slaves near Seoul: “It was not a place for humans, they had sex with me every minute.” (Deutsche Welle, 2013)

The term “labourers” refers to those who were paid for their work. At that time, the majority of the laborers who were mobilised were taken by force, and suffered through performing heavy labour or being sexually abused day and night, as well as from severe malnutrition. All things considered, it’s clear that many Koreans lost their lives in these harsh environments and circumstances. The Japanese labour mobilisation meant “forced free labour” based upon a hierarchical and compulsory culture.

Military regime period

After few years of independence starting in 1945, the country’s second president Park Chung-Hee carried out the May 16 military coup d’état in 1961 and subsequently ruled as a dictator for 16 years, starting in 1963. He exercised his power directly through the military regime and somewhat more indirectly through a hierarchical, manipulative political dictatorship. During these post-colonial times, Park also controlled the entire infrastructure of broadcasting and advertising. Any broadcasts or advertisements in opposition to the military regime were forcibly shut down. In 1972, Park further cemented his grip on power with the so-called October Restoration (유신체제), a highly oppressive strategy for more effectively crushing the resistance. This began with the purpose of establishing a military government by eliminating Democratic forces in order to incapacitate the opposition. If there was a party against Park’s wishes, he eliminated the whole membership of the party, and gave the position to a group of his own followers. Political parties were thus purged and manipulated into factions of loyalists competing for the president’s favours (Seo, 2007). Followers would then focus their efforts on the party who received the most support from the president. Military culture was under high pressure in South Korea under the influence of an authoritarian government (The Korean Herald, 2015). Park, as a former Japanese collaborator, planned a military uprising in order to establish of a new regime of competent generals and loyal core members.

Fig. 6. Korea’s second president Park Chung-Hee in military garb.

President Park’s ruling system has remained as a toxic legacy within modern Korean work culture. For example, all members of a department are expected to collectively suffer any hardships together, thus bonding their fellowship. Any team member with an opinion against the prevailing opinion of the team tends to become alienated from the rest of the team members. Korea has went through a period of rapid change, which influenced the work culture of today’s society. This can be seen in the strict hierarchy in today’s work culture, where seniors make most of the decisions, and junior staff have no voice to question their superiors, but are expected to mindlessly follow orders.

In modern Korean work culture, there is a saying rooted in military culture: “You should stand on the right line”. It means that you should find a strong boss who has a big voice in the company, otherwise you will be eliminated or you won’t have a successful career. As a matter of fact, Korean work culture is a toxic legacy of colonialism and militarism from the early 20th century which introduced the concept of free labour (i.e. slavery). This is a remnant of Japanese colonialism and military dictatorship that has permeated our skins, and has persisted for a long time.

Part 2. The extent of the history: which aspects of work culture in Korean colonial times have been inherited by the digital sphere?

Korea has the fastest and most widely used Internet network in the world (MSIP, 2017). According to one survey, 94% of Koreans are able to access the Internet through a high-speed communication network, with 43.64 million Internet users out of a population of 51 million, and 88.3% of Koreans over 3 years old using smartphones (Yoon, 2017). This is leading Koreans to perform more free labour in the digital sphere than other nationalities.

Digital labour is a concept that has become a crucial foundation of discussions within the realm of the political economy of the Internet (Burston, Dyer-Witheford and Hearn 2010; Fuchs and Dyer-Witheford 2013; Scholz 2012). Users performing digital labour via online activities generate data that is monetised as a commodity by big corporations, without these users being properly paid. These ingenious ways of extracting cheap labour from users show similarities to how natural/human resources were exploited in Japanese colonial times in Korea. I call this phenomenon “digital colonialism”. Of course, this doesn’t mean that the historical colonialism and the modern version are fully identical. Unlike historical Japanese colonialism in Korea, digital colonialism is not bound by geographical location. There are no physical borders, there are only IP addresses, domain names, and user data. Therefore, digital colonialism expands by exploiting more layers of human life itself through the use of technology (Couldry, 2019).

Although it is clear that the modes, intensities, scales, and contexts of today’s digital colonialism are different from historical colonialism, the underlying power structures remain the same (Couldry, 2019). To define the underlying structures, I divided these into three categories: appropriation of human life, dispossession of resources, and domination of economics through manipulation in the form of indoctrination and monopolisation. Through these structures, the impact of the colonial period in South Korea can still be felt today, particularly in the digital space. It is therefore meaningful to look into the specific context and history of South Korea, in order to understand how the negative impact of digital colonialism on people’s lives can be resisted.

2.1 Appropriation of human life

During the Japanese colonisation of Korea, human rights were not considered to be a fundamental principle. The Japanese appropriated Korean territory, and Korean labour, through extreme physical violence. A similar phenomenon can also be seen in digital colonialism, by appropriating the web and our digital selves through our physical bodies, digital labour, and digital life. This becomes indirect exploitation through digital territories, and it gives rise to social and moral problems concerning privacy and surveillance. How did the Japanese appropriate human lives in their colonial times? And how can we see the same phenomenon in modern digital life?

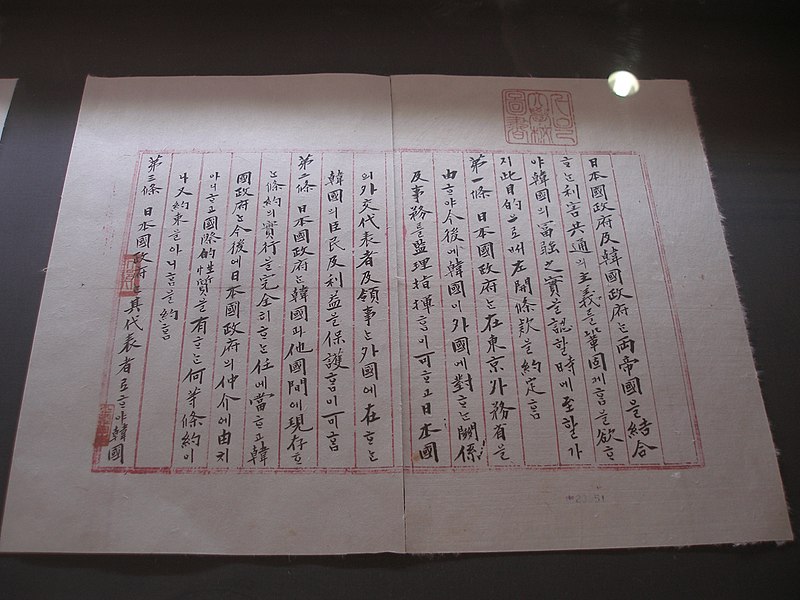

Colonisation was done forcibly to control populations

In 1906, Japan forced Korea to sign the “Eulsa Unwilling Agreement Treaty” or Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty (을사늑약: “Eulsa Neukyak” [“Neukyak” means “coerced agreement”]) which was the first step toward officially becoming a colony of Japan. The treaty was signed through a mix of coercion, threats and deception. A Japanese diplomat, Ito Hirobumi, was dispatched to sign an agreement with Korea. Gojong, the last king of Joseon, refused to sign the Eulsa Unwilling Agreement, so Hirobumi instead held a meeting with a number of Gojong’s ministers, mostly Japanese collaborators. Grabbing a pen and paper, he forced the ministers to agree. At that time, five out of eight ministers (who were called the Five Eulsa Traitors [Eulsa Ojeok]) were more or less forced to agree with the Japanese arrangement. This was signed with the knowledge that Korea would become a colony of Japan. Still they had no choice but to consent. This method was enforced by a small number of people, for Japanese rule to dominate the majority. The meeting resulted in a forced structure that the ministers intentionally had to agree with while knowing the results.

Fig. 7. The original document of Eulsa Unwilling Agreement Treaty.

In modern times, we can notice some similar fundamental characteristics that determine how agreements are signed. As users of high-speed of Internet, Korean Internet users are naturally more exposed than others to terms of service (ToS), privacy statements and user license agreements for using services provided on websites. To sign up on Korean websites, one must fill in information including clicking checkboxes of “terms of service” that are often 5,000 words long. Unless one accepts all the requirements, one can’t sign in and start using the service. Eventually, users always need to accept the agreement without having any possibility of rejecting it. This way of imposing an agreement establishes full control over the majority of users by including a small functionality on the website. By controlling the majority of users with an agreement that is sneakily added in the registration form, these big Korean companies can harvest more free digital labour from their users. I thus conclude that past colonisation and modern times both have a similar fundamental structure which is performed forcibly to control the majority of people.

The 24/7 workplace fosters mental issues that sometimes lead to suicide

In early 1900s, a total of 2679 Japanese workplaces were kept running by more than a million Korean slaves. One of the most accident-prone workplaces was the Takashima coal mine, also known as “Hell Island” (Cha, 2013). Here, Korean slaves were forced to work more than 12 hours every day, so that work consumed their whole life. Many workers died or committed suicide because of the heavy workloads, accidents and mental issues (Dae Hak Nae Il, 2017).

Fig. 8. Korean slaves in front of the Takashima coal mine.

24/7 forced labour was also the fate of the “comfort women” which I mentioned earlier. Korean women from the age of 12 were held in small rooms where they were abused by Japanese soldiers. During this period, Korean women had to serve more than 70 times per day as sex slaves, every day and night. As a result, many struggled with mental issues and many tried to escape (Shin, 2019). Unfortunately, many were also caught while escaping, leading to a mass suicide at a railway track near the city of Chongjin in what is now North Korea (Kyunghyang Shinmun, 2001).

This 24/7 work mentality persists to this day, and has fostered a strange culture of “play” in the digital realm. The relationship between working 24/7 and mental health is reflected in digital media use, especially in Korean gaming culture. More than half of South Korea’s population has developed a high prevalence of gaming and Internet-related problems (Koh, 2015; Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning, 2016), and these are increasingly recognised as a potential public health burden (Kuss & Lopez-Fernandez, 2016; Mak et al., 2014). In 2002, Kim Kyung-Jae, age 24, died from playing a medieval-themed online game for 86 hours. He is believed to be the first person to die from gaming too much, but there would be many more deaths to come (Conti, 2015). We see here a pattern of increasing risk of harmful physical or mental health, sometimes leading to death – consequences typically related to high frequency and a long period of Internet use (King, Delfabbro, Zwaans, & Kaptsis, 2013). Obviously, slavery is forced labour through the physical body, and people in a 24/7 Internet environment are not forced. Still, they are hooked through the addictive design in game interface, and they perform free labour that leads to mental issues. In this sense, the history of the 24/7 work culture that leads to health problems still persists in modern digital society.

Privacy of individuals is infringed

Due to the massive amount of work done throughout the years in the coal-mining area, many Koreans didn’t have an individual human life. In another coal-mining region in Hokkaido, Japan, there was a special forced labour camp called “Tako-beya” for those who had escaped or failed to meet production quota (Dae Hak Nae Il, 2017). The name means literally “octopus room”, referring to the fact that once you get in, you can’t get out because it’s a trap. It was mostly for Korean labourers who had been transported to work mainly in coal mines and on construction sites (Nee, 1974). While trapped in the indentured labour system, a massive amount of innocent workers had to live in overcrowded barracks, being cruelly treated for even minor misbehaviour (Paichadze & Seaton, 2015). Workers were treated like prisoners or worse (Kimura, 2015) and were being checked all the time by the Japanese rulers. They were physically abused, malnourished, and struggled with cold (KBS news, 2015), and of course they couldn’t claim any compensation. In this space, there was no individual or private life during their stay.

In today’s digital society, there is plenty of shocking news on massive data leaks from major companies that have infringed the private Internet life of Korean users. This started in 2008: one of the most mind-blowing examples is a massive data leak from the South Korean web portal site Nate. At that moment, the site was famous for the fact that there was no one who didn’t have an account. In 2011, Nate had the biggest cyber accident, where a total of 35 million subscribers’ IDs, passwords, names, social security numbers, and contacts were leaked due to malware hacking from China. Through this accident, a massive amount of innocent users’ personal information was divulged in a short time (Etnews, 2011), and there was no liability for this personal information leakage (Jeon, 2018). In 2018, malware hacking increased by 400% compared to the previous year (Gil, 2019). Innocent Korean Internet users are in a vulnerable situation in which their data is continuously harvested and sold via illegal websites for a low price (Hee-Kang Shin, 2019). Korean Internet users have no private life on the Internet, and their Internet life has become public without knowing who will make use of their personal data.

2.2 Dispossession of resources

They dispossess(ed) everything from a to z

During the colonial period, Japan took very much from Korea, from natural resources to human resources (물적/인적 자원의 수탈, n.d.) – from fisheries, where the Japanese caught over 5,000 tonnes of fish per day (Kim, 2005), to the agricultural industry, of which approximately 40% was owned by the Japanese government, to the forestry industry, where over 50% of all forests were governed by the Japanese, to mineral resources such as graphite, of which at least 74,879 tonnes was mined every year (Korea Resources Corporation, n.d.). This was an extreme increase in use of natural resources compared to the past in Korea. Besides the aforementioned resources, the Japanese also took scrap metals, brassware, spoons and nails that could be used to make weapons. For airplane fuel, they even forced people to peel pine trees to extract the pine resins. This was an absolute dispossession of everything that might be useful for the development of Japan. In addition, Japan also dispossessed human labour through labour mobilisation, conscription and military “comfort women”, as mentioned in Part 1. These were all forms of forced human labour. Dispossessing human resources happened actively in mines, ports, construction sites, military factories, farms, and the use of “comfort women”. In total, more than 322,644 Korean slaves per year were used as free labourers to produce human resources.

According to Clive Humby, who said that “data is the new oil”, data as a new resource is very valuable and yet easier to generate than any other resource. It doesn’t require much physical labour nor capital. Instead, what is now precious is human life through its conversion into data (Couldry, 2019). Data, as a raw resource, is comprised of the social life of users, and can be produced in everyday life. In her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff states that a company’s products and services are the “hooks” that lure users into their extractive operations, in which our personal experiences are scraped and packaged (Zuboff, 2015). Since data is a new and profitable natural resource, many companies are trying to “hook” a vast amount of Korean users for their data. Over 60% of the South Korean population was using Facebook in 2012, when it overtook Korea’s predominant social media platform Cyworld. The more the number of Facebook users increases, the more personal data is being exploited. I, as one of the many Korean Facebook users, looked into how Facebook controls my data. I was surprised that they could literally access everything I did via Facebook, including my personal information, ads I am interested in, advertisers who uploaded a contact list with my information, files, photos, events, location, payments, search history, and even security and login information.

Besides Facebook, there are more Internet platforms that have vastly dispossessed the data of Korean users. This is due to an increase in data consumption by Koreans, which can be attributed to Korea’s high-speed Internet. Based on statistics that show that 94% of Koreans have access to high-speed Internet, the life of Koreans has become 24/7 interconnected with the Internet, which introduces the Internet as an everyday data-generating platform by users. Korea’s data consumption continues to increase: wireless data traffic statistics show that the total usage of mobile phone traffic of Koreans has exceeded 40TB, as reported by the Ministry of Science and ICT. Smartphone data usage per capita has more than doubled from 3 years ago, when it was nearly 8.09 GB per month. Korean customers’ use of Netflix via smartphones increased 274% over the past year, while YouTube users watched videos for an average of 882 minutes per month (Choi, 2019). As Korean Internet users are increasingly dependent on the Internet, a massive amount of data is more likely to be dispossessed than in other countries.

Dispossession of monetizable resources

With the vast amount of resources and slaves from Korea, Japan’s economy went through a remarkable period of rapid growth during colonial times. Japan’s production indices showed increases of 24 percent in manufacturing, 46 percent in steel, 70 percent in nonferrous metals (“Japanese Economic Takeoff After 1945”, n.d.). Especially Japanese entrepreneurs had a virtual monopoly of Korean trade. More than half of total Korean imports came from Japan and more than 90% of total Korean exports went to Japan (Augustine, 1894). Undeniably, Japan had predominant commercial interests in Korea (Betty L., 2013), exporting products to Korea at expensive prices and importing goods at reasonably cheap prices. In this way, Japan controlled the Korean labour and market.

In modern times, Naver, which is South Korea’s most popular search engine, compiles every single user’s activities in the form of data including personal information, emails, calendar, blog, location, search history, shopping lists and more, to analyse and use for marketing, leading to increase in profits. This is comparably easy because the majority of Korean users use Naver. In contrast to Google’s market share of 13,2%, the share of Naver users in Korea reaches up to 74.4% of the population (Kim, 2019). The same applies for social media platform Kakao, one of whose products is KakaoTalk, a WhatsApp-style messaging service actively used by 97% of all smartphone users in Korea and serving more than 43 million monthly active users. In this way, user data can be easily accumulated and used to generate profits by providing better services. Naver’s digital ads market earned 68.1% of the whole digital market in Korea, an increase of 26.6% since 2018 and the highest ever annual profits and sales. Kakao’s operating profit increased 93% from last year through its service, which has been the largest since 2015.

Based on how these companies have monetised user data, it becomes apparent that the free digital labour of users which generates this data leads to massive profits. Some people make the case that this is not a forced type of dispossession because people are not being physically exploited. However, the means of production in the digital space are not only through the physical body but also in social interactions, a new form of production in the digital colonial era. Moreover, though Korean historical slaves were forced to produce the resources, whereas modern data creation from Korean users is not forced, it is still important to consider these as one single category to discuss. They are still linked through the huge superiors who control their power that gives rise to work/data as monetizable resources. In this connection, dispossession of resources remains in Korean digital society.

2.3 indoctrination & monopolisation

Indoctrinated manipulation

The Japanese indoctrinated Koreans by spreading the term Myeol-Sa-Bong-Gong (멸사봉공), to let Koreans work with passion and loyalty. This concept of Myeol-Sa-Bong-Gong is a vestige of Japanese imperialism that literally means “destroy your personal life and devote yourself for the betterment of your community”. It was used extensively during the 1930s, on instructions of Jiro Minami (南次郞), governor-general of the Japanese occupation government. On 19 April 1939, Minami taught lessons in establishing a new Japanese palace in Cheong-Nam Korea, the reinforcement of soldiers, and the enhancement of the principle of imperialism in order to implant the greatness of the Japanese Empire (Lee, 2012). With this as a fundamental brainwashing method, Japan succeeded in controlling a huge forced Korean army that participated in the Asia-Pacific War (태평양전쟁) during World War II. This was known as conscription, a part of the national mobilisation laws which Japan pursued, and which I discussed in Part 1. During the war, Japan mobilised more than 120,000 young Koreans including 18,594 special army supporters, 3,050 school volunteer soldiers, 1,000 navy special forces who volunteered under the strict military hierarchical system. Controlling this huge amount of people was possible through the indoctrination and manipulation of Myeol-Sa-Bong-Gong.

Today’s digital culture in South Korea certainly has traits that were influenced by this colonial history. Surprisingly or not, Korean users have been still indoctrinated by decades of Myeol-Sa-Bong-Gong, which has found its way to the digital realm. It shows in the normalisation of users’ mindsets that have been altered to fit certain behaviours. In the 1990s and early 2000s, when Korea just started using the Internet, it wasn’t normal to be online or being on the phone for long spans of time every day. Today, it has become normal to stay online on the Internet environment, every day, 7 days a week. Since many people have a second phone, a laptop and even extra digital devices like an iPad, the merging of digital social life and Korean advertising platforms such as Naver Blog has made users indoctrinated through these circumstances. Manipulation also happens through interface design. A great example of this would be infinite scrolling: Infinite scrolling is one of the manipulative ways generally used on e-commerce websites to keep users focused on the website. For example, “Yo-Gi-Yo”, an online website for food delivery, shows infinite amounts of restaurants while scrolling; in this way, users are manipulated by the interface of the website. With this Internet activity, users remain on the website without noticing it, which may certainly be directly connected to the company’s profits.

Monopolised manipulation

President Park Chung-Hee exercised his power through a military regime and political dictatorship, which widely manipulated Korean media and advertisement industries from the 1950s onward. Media manipulation was done by controlling political discourse in the media. One striking example was the Dong-A newspaper company’s “blank paper advertisement” situation. In 1964, all the advertising companies, who had signed to place their ads in the Dong-A newspaper, were cancelled due to the media suppression of Park’s regime. As a result, the paper was filled with half-blank pages with only small amounts of text. Television broadcasts also had to skip advertisements in between TV programmes. Due to the media manipulation guided by Park, the newspaper company couldn’t publish any advertisements for seven months, leading to management difficulties. In the end, the paper’s internal unrest was ended by firing employees who protested against Park’s military dictatorship (Hwang, 2017).

Fig 9. Half-blank pages in the newspaper Dong-A in 1964.

One of the major mobile research providers, Open Survey, stated in the newspaper Joong-Ang that the majority of the Korean population are Naver users. This means that Naver has a dominant market share in the digital society, with a tremendous amount of users (JoongAng Ilbo, 2019). To explain the monopolised manipulation in Korean digital society, Naver’s “cage culture” is a perfect example of manipulation happening through a digital monopoly. Naver limits consumers’ choices by manipulating search results, infringing on search neutrality (the principle that searchers should show fair results without any bias or other consideration) by providing manipulated information. Instead of fair search results, users are exposed to manipulated results that lead to increased profits for Naver. In doing so, the platform abuses its monopoly position to generate maximum profit, and mistreats its contents and users by providing non-neutral search results.

In the second chapter, I investigated how the specific history of Japanese colonialism in South Korea has remained in digital corporate society. It has become evident that this history still lingers on in the form of stealing resources through privacy infringements, negative impacts on mental health, social media and game addiction, and loss of time that could be used for more meaningful activities such as the Korean traditional labour sharing method of “Pumasi”, which I described earlier in this text. Although there is a great deal of evidence of persisting tendencies in the digital realm, users have become unwitting victims in the digital society. In the next part, I will explore how we can make this more palpable in order to create a sense of urgency, and what we can do within the system by analysing existing projects.

Part 3. How can we make this situation palpable in order to create a sense of urgency?

Since we have discovered that the culture of free labour inherited from Japanese colonialism in Korea has remained in the digital realm, the question is: what should I do? This is a good opportunity to reflect on how we can make the problem of digital free labour more palpable. The original meaning of “palpable” is: “capable of being physically touched or felt in a tangible way” (Merriam-Webster, 2020), but here, the way I use the word “palpable” is to indicate “real experiences”, “easily perceptible”, and “easy to manifest” – so it is almost tangible even though it’s not physically directed at you.

Then, do we want to quit using these platforms? In theory, this seems ideal. However, quitting these platforms that compel us to perform unpaid labour is not an optimal solution because, realistically, we can’t quit, and the problem is also in the platform’s business model. Many users, who need to attract customers for their own business online, are unable to quit because their livelihoods depend on the platform. In addition, as means of communication with friends and family have dramatically become digital these days, using such platforms is almost inescapable. Furthermore, the business model of these platforms is not in producing products, but in targeting users with online advertising and in analysing massive amounts of data. In doing so, these companies can determine which users receive which sponsored links on each results page. For them, user data results in more lucrative transactions. Therefore, they sneakily announce in their terms of service that they will take the user’s data, and make us perform digital labour in ways that the companies can capture and convert into data (Zuboff, 2015).

It’s no secret anymore that they collect my data when I visit websites. However, everyone seems unaware of the fact that they are working hard, indifferent to the reality of being exploited for the profit of large corporations – a description that closely resembles modern colonial slavery. We’re aware of big companies taking our data, but still we remain on their platform 24/7. Nobody is forcing us to work, but we’re still voluntarily producing our own data and value for others in a non-reciprocal way. How can we have a discourse that makes this topic palpable? As self-aware digital workers, how can we become more aware of our own autonomy, our labour, and the data we produce? Can we create a sense of urgency so that everyone can be palpably aware of free labour? To create a sense of urgency, what can we do within the system? In the following part, I will discuss, by analysing various projects, different ways in which this sense of urgency can be achieved. In doing so, I aim to increase awareness of the issues at hand.

3.1 Knowing what you’re signing on for

When we make a new account on any Internet platform in Korea, we have to agree to certain terms and conditions. As I pointed out in part 2, there is no way to disagree with these terms if we want to join the community or use the system. Users are basically forced to sign privacy agreements in order to start using these services, and companies are free to do pretty much anything they want. My first personal activist suggestion toward creating a sense of urgency is: “being aware of what I am signing up for while using platforms”. We will not know about what’s happening with our data if we are unaware of the contents of the agreement the platform has provided for us. It’s important to understand what’s in these agreements, and to act out by carefully reading the terms of service and privacy policy (“Terms of Service; Didn’t Read”, n.d.). It’s clear that these terms of service (ToS) are often too long to read, and placed in a very obscure part of the web interface. Also, the use of “legalese” and the difficulty of most users in understanding this language, are all used to obfuscate the content, making it difficult to figure out the terms I am about to agree to.

A web-based project called Terms of Service; Didn’t Read (ToS;DR) is an excellent example of how users can become more aware of what they’re signing. ToS;DR is a community project that aims to analyse and grade the terms of service and privacy policies of major Internet sites and services, by translating the original text of a ToS into simple and direct language. This helps users to explicitly understand the main points of the agreement that websites are making with their users. The ToS;DR website also helps us to easily understand the meaning of each sentence by filtering out the obfuscation of words, and opening up a community discussion space where everyone can freely voice their opinions. In doing so, each platform is given a rating that can potentially help users to be more informed about their rights.

3.2 Digital self-tracking

“Every day most of us contribute to an evolving public presentation of who we are that anyone can see and that we cannot erase.” – Digital Citizenship Adventures (2015)

As an Internet user, having a digital footprint is normal, and very difficult to avoid. Such a digital footprint broadly includes: all the emails you’ve ever sent, every post you’ve shared on social media, and every artificial intelligence lifestyle product that has guided your daily life in a better way. A Korean AI lifestyle product called “Kakao Mini” scrapes all personal experiences based on a user’s lifestyle, revealing the privacy and security consequences in which sensitive household and personal information are shared with other smart devices and third parties for the purpose of sales to other unspecified parties (Zuboff, 2019). Nevertheless, many people don’t really care about data leaks, because they don’t feel closely attached to their data. It’s also undeniable that these platforms produce many benefits for users. We could prevent being tracked by removing metadata from pictures before posting them online, or by regularly checking privacy settings – however, this is not easy to do, and not everyone can do it regularly because it’s technically challenging and time-consuming.

To make digital free labour more palpable, we need to clarify how we can retain control of the data we produce, and what our digital footprints look like. Therefore, my second suggestion is to become more aware of what we are creating by self-tracking own digital footprints and finding ways to protect ourselves from being tracked. Self-tracking is not a new phenomenon. For centuries, people have used self-monitoring as a means to attain knowledge and understanding about themselves (Nair, 2019). Self-tracking one’s digital footprint, for the purpose of becoming more aware of the possibilities of being tracked by third parties, prevents companies from spying on individuals, and protects the individual’s own personal information and digital activities. Moreover, it also provides insight into how the website is tracking you, what information they are gathering from you, and who is tracking your web-surfing habits.

Unlike the EU, where the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is in force, Korea has almost no data protection law. This makes it harder for Korean users to self-track their own digital footprint. All the time, browsers are busy extracting data from the digital free labour of users. Data brokers track us across sites, while Internet service providers load the pages we visit and attempt to harvest the data we produce. To protect yourself from being tracked, the use of a secure browser app such as Ghostery would be a good choice. This is a web browser extension that blocks trackers in order to protect the entire web browser, allowing you to regain control of your data. The app safely shields the activity of users while also evading intrusive ads that slow download times (Ghostery Midnight, 2009). A self-tracking mobile app called Lumen Privacy Monitor by The Haystack Project analyses your mobile traffic to identify privacy leaks inflicted by your apps and the organisations collecting this information (ICSI Haystack Project, 2017). Disconnect.me is a similar project that tracks and shows the number of tracking requests on a page by companies, and which content is being tracked (Disconnect.me, 2011). These apps find out how installed apps behave in the network, and how they extract or leak privacy-sensitive information, helping us to stay in control of our own network fingerprints. Through the apps, a short time divulgence of a massive data leak can be prevented, thus improving the Internet by empowering people to exercise their right to privacy (Disconnect.me, 2011). This can be very useful in Korean platforms to prevent users being tracked without knowing it.

3.3 Quantifying the problem

Providing numeric values on the quantity of data is the most palpable way to create a sense of urgency because it makes it more tangible and easier to get a sense of the volume of data. This is called quantitative research, a research method based on measuring phenomena and analysing statistical, mathematical, or computational results (Given, 2008). In the quantification of digital free labour, the analysis can include the volume of data, the amount of time spent on the web, or the amount of code executed while using the Internet platform.

It’s clear that tech companies alter their algorithms to control how people use the Internet in order to ultimately normalise certain new types of human behaviour (Rattle, 2010). Quantifying data could help change the user’s mindset of normalising certain behaviours of using Internet platforms for long periods of time. The Hidden Life of an Amazon User by Joana Moll is an example that reveals the environmental footprint of buying a book on Amazon, the volume of information transmitted, and how business revenues are generated by tracking the customer’s behaviour (ARS Electronica, n.d.). Another direct example of quantifying data is the Web Activity Time Tracker, a Chrome extension for tracking one’s own daily Internet activity through the browser, calculating the total amount of browsing time for each day and for individual websites, and showing the results in a CSV file. Using this extension, users potentially won’t remain anymore on one single searching platform such as Naver. If Korean users would see how much time they spend on the platform, perhaps they would start to look for alternative platforms where users can be more aware of controlling their data. Another way to prevent normalising certain behaviours of users is by controlling the scrolling of users on the web. A web browser app called Disable Scroll Jacking is a Chrome extension that does just what it says: it stops unintentional scrolling on all websites, showing a full-screen message when it catches you scrolling too long (Make Scrolling Bearable Again, n.d.). This will help users avoid being influenced to engage in infinite scrolling caused by the interface of the website. By quantifying data, they can have a real experience of how much free digital labour has been generated from their Internet activities (Alex, 2020).

Throughout part 3, I have suggested that these three ways to make digital free labour more palpable could potentially help users become more self-aware of what’s happening around them – especially people who are vastly exposed to the digital world, as Korean Internet users are. I must say that the palpable approach will not be able to completely solve the problem of digital free labour culture. However, it is a small gesture to increase self-awareness in a more tangible way. With this approach, the attitude toward digital platforms will change from indifference to increased awareness of the way we position ourselves using the Internet.

Part 4. Conclusion

There is a widespread perception that Japan’s 35 years of colonial rule improved Korea’s infrastructure, education, agriculture, other industries and economic institutions, and thus helped modernise Korea (Japan Times, 2019). However, one should not forget the discrimination and suffering that Koreans experienced under a hierarchical colonial rule that remains as a toxic legacy of colonialism, particularly in Korean work culture. Eventually this has transferred to the culture of exploitative labour under the concept of digital colonialism in the digital realm. It has become more apparent that the idea of colonialism seems to be an eternal loop that comes back throughout history. Although I have focused on colonialism in a specific context within South Korea, it is essential not to ignore that digital colonialism is applicable to countries other than Korea, regardless of their history. It’s a worldwide phenomenon that everyone should be aware of.

Throughout the essay, I have highlighted a situation where Korean Internet users are unaware of the extent to which data harvested from their online activities is monetised by digital companies. I presented this as digital colonialism, a form of labour exploitation, and attributed the situation to three specific factors: the high extent of Internet usage in Korea, the relative lack of legislative protection for Internet users, and the cultural acceptance of this situation. Dismantling the historical colonialism experienced by Korea under Japanese rule and digital corporate society, I identified a toxic legacy of colonial rule in digital space that has become entrenched in modern-day life. And by pointing out the inheritance of colonialism, I have set some templates for how making the situation more palpable might encourage users to resist it.

While reading this essay, you may have questioned the proposed solutions. Finding a solution to the problem of digital colonialism and its negative impact on people’s lives is necessary. However, this essay doesn’t aim to solve the current situation of digital colonialism. Instead, it focuses on helping people realise what situation they’re in – to understand what digital colonialism is, that it is inherited, that it continues in different forms and ways – by creating a small gesture that makes these things tangible, in order to spark self-awareness. Colonisation might feel like a heavy topic to discuss; however, if we think of colonisation as a way to become aware of a work ethic that makes us vulnerable to exploitative practices in the digital realm, this might be a good moment to look at the situation critically in a different perspective. By making the situation palpable in our minds, we may hopefully be able to shift the way we look at this situation and how we position ourselves when using the Internet.

Bibliography

-

ARS Electronica (n.d.) The Hidden Life of an Amazon User. Available at: http://ars.electronica.art/outofthebox/en/amazon/ (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

-

Alex, (2020) Stigmatoz/web-activity-time-tracker. Available at: https://github.com/stigmatoz/web-activity-time-tracker (Downloaded: 8 March 2020).

-

Augustine Heard, (1894) “China and Japan in Korea,” North American Review, Vol. CLIX (July-December 1894), p. 301.

-

Betty L.K. (2013) Japanese Colonialism and Korean Economic Development, 1910-1945. 1st ed. The Philippines: Asian Center, University of the Philippines Diliman, pp. 1-10.

-

Blakemore, E. (n.d.) The Brutal History of Japan’s ‘Comfort Women’. Available at: <https://www. history.com/news/comfort-women-japan-military-brothels-korea> (Accessed: 18 February 2020).

-

Brett Nee, (1974) ‘Sanya: Japan’s Internal Colony’, Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 6, no. 3 (1974): 14.

-

Burston, Jonathan, Nick Dyer-Witheford and Alison Hearn, eds. (2010) Digital Labour: Workers, Authors, Citizens. Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization 10 (3).

-

Caprio, M. (2009) Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea, 1910–1945. University of Washington Press. pp. 82-83.

-

Cha, H.B. (2013) [오늘의 세상] “아소 家門(망언 日부총리의 증조부와 父親)이 경영한 탄광, 강제징용 1萬 조선인의 지옥” - 조선닷컴 - 국제 > 국제 일반 (n.d.). Available at: http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2013/08/21/2013082100231.html(Accessed: 24 February 2020).

-

Choi, S.J. (2019) 월 데이터 사용량 “40TB” 돌파한 한국 – 시사위크 (2019). Available at: <http://www.sisaweek.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=119224> (Accessed: 9 March 2020).

-

Conti, A. (2015) Gamers Are Dying in Taiwan’s Internet Cafes. Vice. Available at: https://www.vice.com/da/article/znwdmj/gamers-are-dying-in-taiwans-internet-cafes-456 (Accessed: 24 February 2020).

-

Couldry, N. and Mejias, U.A. (2019) The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating it for Capitalism. Culture and Economic Life. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

-

Dae Hak Nae Il, (2017) 군함도보다 악명 높았던 일본 강제동원 지역들 (n.d.). Available at: https://univ20.com/14160(Accessed: 24 February 2020).

-

Disconnect.me (2011) Disconnect.me. [online] Available at: https://disconnect.me/disconnect (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

-

Etnews, (2011) 네이트, 해킹 사고로 개인정보 유출. Available at: https://www.etnews.com/201107280080?SNS=00002(Accessed: 29 February 2020).

-

Finley, K. (2017) Pied Piper’s New Internet Isn’t Just Possible – It’s Almost Here. Wired, 1 June. Available at: https://www.wired.com/2017/06/pied-pipers-new-internet-isnt-just-possible-almost/ (Accessed: 5 March 2020).

-

Fuchs, C. and Sevignani, S. (2013) What Is Digital Labour? What Is Digital Work? What’s their Difference? And Why Do These Questions Matter for Understanding Social Media?. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 11(2), pp. 237-293.

-

Galstyan, M. and Movsisyan, V. (n.d.) Quantification of Qualitative Data: The Case of the Central Bank of Armenia, (33): 14.

-

Ghostery Midnight (2009) [online] Available at: https://www.ghostery.com/midnight/ (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

-

Gil, M.G. (2019) [G-PRIVACY 2019] “최근 4년간 개인정보 유출 80.5%가 해킹 등 외부공격이 원 인”(2019). Available at: https://www.dailysecu.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=48726 (Accessed: 29 February 2020).

-

Given, Lisa M. (2008) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Los Angeles.

-

Ha, Y. (2012) Lee, Hong Yung, Yong-ch’ul Ha, and Clark W. Sorensen, eds. Colonial Rule and Social Change in Korea, 1910-1945. Seattle: Center for Korea Studies Publication, University of Washington Press, 2013.

-

Ham, G. J. (2017) “한국인이 알아야 할 조선의 마지막 왕, 고종”, 자음과모음 press, ISBN 9791187858782.

-

Hwang, (2017) [백 투 더 동아/12월 26일]‘백지 광고 사태’ 때 격려 광고 1호는 누구?(2017). Available at: http://www.donga.com/news/article/all/20171225/87894470/1 (Accessed: 18 February 2020).

-

ICSI Haystack Project (2017) [online] Available at: https://haystack.mobi/ (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

-

“Japanese economic takeoff after 1945” (n.d.). Available at: http://www.iun.edu/~hisdcl/h207_2002/jecontakeoff.htm (Accessed: 9 March 2020).

-

Japan Times, (2019) The Annexation of Korea / The Japan Times (n.d.). Available at: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2010/08/29/editorials/the-annexation-of-korea/#.Xclv0S2ZPUI) (Accessed: 11 December 2019).

-

Jeon, H.J. (2018) 대법 “네이트·싸이월드, 개인정보 유출 배상책임 없어” (2018). Available at: https://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/01/28/2018012800443.html (Accessed: 29 February 2020).

-

JoongAng Ilbo, (2019) [ONE SHOT] ‘네이버’ 검색포털 점유율 압도적 1위...검색 결과 만족도는? Available at: https://news.joins.com/article/23459477 (Accessed: 13 April 2020).

-

Jung, A.G. (2019) 식민지 군사동원의 경험과 유산, 그리고 기억 (n.d.). Available at: http://www.mediawatch.kr/news/article.html?no=254110 (Accessed: 18 February 2020).

-

KBS news, (2015) [사회] 70년 만의 귀향...홋카이도 강제노동 유골 115위 봉환(2015). Available at: http://world.kbs.co.kr/service/contents_view.htm?lang=k&menu_cate=&id=&board_se-q=261366 (Accessed: 25 February 2020).

-

Kang, T. (2006) Hanʼguk minyohak ŭi nolli wa sigak. Chopan. Sŏul-si: Minsogwŏn.

-

Karube, Tadashi, and David Noble. (2019) Toward the Meiji Revolution: The Search for “Civilization” in Nineteenth-Century Japan = “Ishin Kakumei” e No Michi: “Bunmei” o Motometa Jūkyūseiki Nihon. First English edition. Japan Library. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, 2019.

-

Kasulis, K. (2017) South Korea’s Play Culture Is a Dark Symptom of Overwork – Quartz (n.d.). Available at: https://qz.com/1168746/south-koreas-play-culture-is-a-dark-symptom-of-overwork/ (Accessed: 16 November 2019).

-

Kim, B.J. (2017) http://hyundaenews.com/28599

-

Kim, C. (1992) Pumasi wa chŏng ŭi inʼgan kwanʼgye. Hanʼguk illyuhak chongsŏ 2. 1st-pan ed. Sŏul Tŭkpyŏlsi: Chimmundang.

-

Kim, K.J. (2019) [ONE SHOT] ‘네이버’ 검색포털 점유율 압도적 1위...검색 결과 만족도는? Available at: https://news.joins.com/article/23459477 (Accessed: 1 March 2020).

-

Kim, S. (2005) Mackerel Fishery and Japanese migrant fishing village During the Period of the Japanese Imperialistic Rule. Korea Historical Folklore Institute, [online] (20), pp.165-190. Available at: http://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE01770227&lan-guage=ko_KR (Accessed 29 Feb. 2020).

-

Kim, T.G. (1995) 품앗이 – 한국민족문화대백과사전 (n.d.). Available at: <http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/ Contents/Index?contents_id=E0060329> (Accessed: 2 December 2019).

-

Kim, Y.H. (2017) 보도자료 | 과학기술정보통신부. Available at: <https://www.msit.go.kr/web/msip- Contents/contentsView.do?cateId=_policycom5&artId=1289520> (Accessed: 13 May 2020).

-

Kim, Y.J. (2017) 한국학생 “삶의 만족도” 48개국 중 47위 - 조선닷컴 - 사회. Available at: <https:// news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2017/04/21/2017042100131.html> (Accessed: 12 May 2020).

-

Kimura, K. (2015) Retracing Forced Laborers’ Journey, Koreans Finally Bring Their Loved Ones Home from Hokkaido. Available at: <https://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2015/11/18/ issues/retracing-forced-laborers-journey-koreans-finally-bring-loved-ones-home-hokkaido/> (Accessed: 25 February 2020).

-

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Zwaans, T., & Kaptsis, D. (2013) Clinical features and axis I comorbidity of Australian adolescent pathological Internet and video-game users. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 47, 1058-1067.

-

Koh, Y-S. (2015) The Korean national policy for Internet addiction. In C. Montag & M. Reuter (eds.) Internet Addiction: Neuroscientific Approaches and Therapeutical Interventions. (pp. 219-233). Springer International Publishing.

-

Korea Resources Corporation, (n.d.) 일제강점기- 광업의 역사 -한국광물자원공사(n.d.). Available at: https://www.kores.or.kr/views/cms/hmine/mh/mh05.jsp (Accessed: 29 February 2020).

-

Kuss, D. J., & Lopez-Fernandez, O. (2016) Internet addiction and problematic Internet use: A systematic review of clinical research. World Journal of Psychiatry, 6, 143.

-

Kyunghyang Shinmun (경향신문) (2001) 북한주민이 증언하는 일제시대 위안소. Available at: <http://truetruth.jinbo.net/bbs2/zboard.php?id=true_news&page=173&sn1=&- divpage=1&sn=off&ss=on&sc=on&select_arrange=headnum&desc=asc&no=83> (Accessed: 24 February 2020).

-

Lee, G.B. (2019) “고종 “내가 살해돼도 특명다하라””…112년전 헤이그특사 인터뷰 | 연합뉴스. Available at: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20190311159500082 (Accessed: 25 February 2020).

-

Lee, S.Y. (2017) 조선인 강제징용, 군함도는 극히 일부였다 (2017). Available at: <https://news.chosun. com/site/data/html_dir/2017/07/20/2017072002589.html> (Accessed: 18 February 2020).

-

Lee, Y.O. (2012) 이순신 장군이 “멸사봉공”? 뜻이나 알고 쓰나 (2012). Available at: <http://www. ohmynews.com/nws_web/view/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0001810313> (Accessed: 18 February 2020).

-

Lee, Y.O. (2013) 일본왕을 위한 알고나 쓰나? (n.d.). Available at: <http://www. koya-culture.com/news/article.html?no=91287> (Accessed: 18 February 2020). Make Scrolling Bearable Again (n.d.) Available at: <https://joshbalfour.github.io/disable- scroll-jacking/> (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

-

Merriam-webster.com. (2020) Definition of PALPABLE. [online] Available at: <https://www. merriam-webster.com/dictionary/palpable> [Accessed 7 Mar. 2020].

-

Michael M. Boll (January 13, 2015) Cold War in the Balkans: American Foreign Policy and the Emergence of Communist Bulgaria 1943–1947. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-0-8131-6217-1.

-

Ministry of Government Legislation (1988) Korean Constitutional Rights from National Law Infomation Center. Available at: <http://www.law.go.kr/%EB%B2%95%EB%A0%B9/%EB%8C% 80%ED%95%9C%EB%AF%BC%EA%B5%AD%ED%97%8C%EB%B2%95#J37:0> (Accessed: 24 February 2020).

-

Moon, H.G. (2017) 미디어오늘 (2017) “사냥감은 13세, 14세의 소녀들이었다.”Available at: <http:// www.mediatoday.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=136902> (Accessed: 24 February 2020).

-

Nam, K.D. (2018) [Graphic News] Koreans work third-longest hours in OECD(n.d.). Available at: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20180501000620 (Accessed: 19 February 2020).

-

Nair, L.A. (2019) Self-Tracking Technology as an Extension of Man. M/C Journal, 22 (5). Available at:http://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/view/1594 (Accessed: 13 May 2020).

-

Paichadze, S. and Seaton, P.A. (eds.) (2015) Voices from the shifting Russo-Japanese border: Karafuto/Sakhalin. Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia 105. New York, NY: Routledge. <https://books.google.nl/books?hl=en&lr=&id=lH_ABgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT81&dq= takobeya&ots=si_sfLQzTa&sig=BgvultK0HwP_JxkW9atG9MKwXAI#v=onepage&q=takobeya& f=false>

-

Park, J. (2017) South Korea’s Rigid Work Culture Trickles Down to Young Startups (2017). KOREA EXPOS. Available at: https://www.koreaexpose.com/south-korea-rigid-work-culturestartups/ ( Accessed: 18 February 2020).

-

Rattle, R. (2010) Computing our way to paradise? the role of internet and communication technologies in sustainable consumption and globalization. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield.

-

Ryu, H.C. (2019) “年 과로사 457명, 탄력근로제는 의사들이 인정한 산재 인정 조건”(2019). Available at: http://www.nocutnews.co.kr/news/5237058 (Accessed: 18 February 2020).

-

Samson·Asia·March 27, C. and Read, 2018·3 Min (2018) Korea Has a Unique Kind of Love That is Extremely Difficult to Explain to Foreigners. Available at: https://nextshark.com/jeong-korea-unique-kind-love-extremely-difficult-explain-foreigners/(Accessed: 2 December 2019).

-

Seo, C. (2007) 한국현대사 60년. 1st-pan ed. Sŏul-si: Yŏksa Pipyŏngsa.

-

Shin, H.K. (2019) “해킹 ID 팝니다”...韓 개인정보 불법유통 44만건 시대. Available at: <http://biz. newdaily.co.kr/site/data/html/2019/11/25/2019112500069.html> (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

-

Shin, S.M. (2016) ‘멸사봉공(滅私奉公)’이란 용어에는 과연 식민지 잔재가 담겼을까? : 조선pub (조선 펍) > pub (n.d.). Available at: <http://pub.chosun.com/client/news/viw.asp?cate=C03&nNews- Numb=20160219440&nidx=19362> (Accessed: 18 February 2020).

-

Shin, S.M. (2019) “하루 70명 상대...” 증언한 위안부 처벌한 일제. Available at: <http://www. ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/View/at_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0002582574> (Accessed: 24 February 2020).

-

Scholz, T. (ed.) (2013) Digital labor: the Internet as playground and factory. New York: Routledge. Terms of Service; Didn’t Read (n.d.) Available at: https://tosdr.org/ (Accessed: 3 March 2020). The Hankyoreh News, (2007) “위안부 중 52%가 조선인이었다” : 사회일반 : 사회 : 뉴스 : 한겨레 (n.d.). Available at: http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/253298.html (Accessed: 18 February 2020).

-

The Korean Herald. (2015) [Weekender] Origins of Korean work culture - The Korea Herald ( n.d.). Available at: <http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20150116001008&ACE_ SEARCH=1> (Accessed: 16 November 2019).

-

Woo, J.H. (2007) 삼강오륜의 현대적 조명. 이화.

-

Yoon, C.H. (2004) “Nate seen top portal; Daum begs to differ”, JoongAngDaily, June 29,

-

Retrieved on September 28, 2007.

-

Yoon, S.J. (2017) 국내 인터넷이용자 수 4364만명…스마트폰 보급률 85% - 노컷뉴스 (n.d.). Available at: https://www.nocutnews.co.kr/news/4724856 (Accessed: 1 March 2020).

-

Zuboff, S. (2015) Big other: Surveillance Capitalism and the Prospects of an Information Civilization. Journal of Information Technology, 30 (1): 75–89. doi:10.1057/jit.2015.5.

-

Zuboff, S. (2019) The age of surveillance capitalism: the fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. First edition. New York: PublicAffairs.

-

우리역사넷 (n.d.) Available at: http://contents.history.go.kr/mobile/ta/view.do?levelId=ta_m71_0100_0010_0030_0020 (Accessed: 29 February 2020).

-

을사늑약(을사조약)의 체결 과정 (n.d.) Available at: https://blog.naver.com/sport_112/221274775717 (Accessed: 24 February 2020).

-

을사늑약에 대한 우리 민족의 저항 (n.d.). Available at: https://blog.naver.com/sport_112/221275850167 (Accessed: 24 February 2020).

Images

-

Fig. 1. Lee, K.C. (2011) 품앗이 테스팅 그룹, accessed 13 May 2020 https://powerjessielove.wordpress.com/2013/06/12/gimcheon-family-community/

-

Fig. 2. South Koreans are working themselves to death. Can they get their lives back?, accessed 13 May 2020 https://read01.com/5MP5MkG.html#.XwgntJMzbRY

-

Fig. 3. Lee, S.M. (2018) 혼술남녀 - 혼밥 트랜드인가? ”, accessed 13 May 2020 https://m.blog.naver.com/PostView.nhn?blogId=mrrah&logNo=221287747924&proxyReferer=https:%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F

-

Fig. 4. Lee, S.Y. (2017) 조선인 강제징용, 군함도는 극히 일부였다, accessed 13 May 2020 https://m.news.zum.com/articles/39603757

-

Fig. 5. Moon. H.G. (2017) 1944년 9월 연합군이 송산 위안소에서 살아남은 위안부들을 찍은 사진, accessed 13 May 2020 https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20161229051600004

-

Fig. 6. Post by 최태성 Twitter, accessed 13 May 2020 https://twitter.com/bigstarsam/status/996519020542156800

-

Fig. 7. Ryu, C. (2011) 을사조약문, accessed 13 May 2020 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jeongdong19.jpg

-

Fig. 8. Dae Hak Nae Il (2017) 군함도보다 악명 높았던 일본 강제동원 지역들, accessed 13 May 2020 https://univ20.com/14160

-

Fig. 9. Huh, M.M. (2013) The Hankyoreh Newspaper, 박정희 정권 언론탄압… 동아일보 ‘백지광고’사건, accessed 13 May 2020 http://www.donga.com/news/article/all/20130716/56469261/10