Networks of Care

Introduction

Knowing how to deal with hate is a precondition of using any social media website today. There are a few ways of managing the massive number of aggressions we see online, and for me, practices of moderation became essential to enjoy and participate in social platforms. More and more, I want to filter my online circles and be selective with my interactions. This way, social networks can make me feel connected with the people I want. My research departs from a personal urgency to be mindful of the existing strategies and tools to reduce hate on social media.

Throughout this text, I will refer to hate as actions that harm others. Hate can be expressed through many different behaviours, and it’s hard to identify these without context. The most common demeanours are harassment, bullying, stalking, racism, threats and intimidation. These problems are getting more attention as we acknowledge online behaviours aren’t confined to screens but have repercussions on our bodies. Furthermore, research shows that marginalised groups are bigger targets of hate speech (Silva et al., 2016). In this matter, it becomes crucial to address the recurring problem of online hate.

There is no single solution to handle hostility but many different measures. A fair answer is to insist on responsibility either from governments, tech companies, or international organisations. Besides changes in official structures, it’s stimulating to look at bottom-up strategies initiated by users. In the forefront of the fight against hate, there are users committed to creating better social media experiences for themselves and for others. These users offer support with their work on moderation, technical knowledge, emotional labour, and many more. Such efforts are mostly made by volunteers, with no formal responsibilities besides the aim to improve and enjoy their social networks. These are very generous approaches, and I believe they need to be further discussed and recognised.

Starting from this conviction, I want to provide a deeper understanding of community movements that moderate online platforms. In the first part of this thesis, I look into digital vigilantism through cancel culture, an approach for calling out problematic people. In the second part, I dive into Codes of Conduct, another possible way to manage behaviour. In the last section, I explore design tools that can hold off instances of abuse, such as blocklists. This text collects memories and evidence of these techniques and analyses them, reflecting on which moderation strategies have been growing on online networks.

I delve into the labour, efforts and motivations behind the communities regulating their spaces with care. It’s exciting to consider which gestures may contribute to increasing autonomy and cooperation in digital platforms, and whether they can be useful to reduce hate, or even desirable. These speculations all motivate my research question – what kinds of methods, users and tools can help to manage online hate?

Chapter 1: Fighting hate with hate: the case of cancel culture

Digital vigilantism is an ongoing movement that identifies and prosecutes hateful content outside of traditional legal ways. It often takes place on community-run online platforms, where justice-seekers get together to supervise social networks. Right now, the most popular approach of digital vigilantism is cancel culture. This movement creates communities with shared mindsets, rules and goals, which collectively moderate online participation. In this chapter, I will take cancel culture as a case study to discuss how users are overseeing their social spaces through particular contentious methods.

Cancel culture evolved from the need to raise awareness for problematic behaviour online. When a mediatic figure does something unacceptable in the eye of the public, the outrage begins. Users shame others for reasons such as using hate speech, writing racist comments, making misogynist remarks, or any other behaviour perceived as unreasonable. The number of people that participate in the callout affects how viral the reaction on social media is – the shamed may lose followers, sponsors or job opportunities, or suffer other kinds of punishment. In short, they become cancelled. As researcher Lisa Nakamura explains, in the attention economy, when you find someone not worthy of your attention, you deny them their sustenance (Bromwich, 2018).

When it started, cancel culture was supporting the voiceless. The users standing by the movement wanted to establish a more caring society, to show concern for marginalised groups that are frequently silenced and harassed on social media. Users were criticising the careless exposure of hateful content, mainly coming from high-profile members of social spaces. It makes sense: the online accounts of renowned brands, businesses or celebrities are powerful channels in which ideas are broadcast to vast numbers of people. For instance, if a prominent identity describes women in a derogatory way, they are sharing these values through a huge network, their followers. The cancel movement condemned these cases and challenged the status of the elites that can often avoid the consequences of their harmful behaviours. If the outrage against a powerful identity was loud enough, it produced reactions and triggered discussions.

The popularity of cancel culture brought problematic situations to the attention of the public, which put pressure on gatekeepers to decide what is or isn’t allowed inside their platforms. Cancel culture pushes social media platforms to act politically towards users, something that these businesses have been avoiding. In the US, publishers such as traditional newspapers are curators, so they bear responsibility for what is published. US laws declare that an “interactive computer service”, such as Facebook, is not a publisher (Communications Decency Act 1996). This means that computer services can’t be held accountable for what their users publish. However, when Facebook starts banning content and deciding what is appropriate to share, it’s making editorial decisions that resemble the procedures of newspapers. The contours of the law are unclear. Furthermore, social platforms are corporate multinational businesses, which makes it even harder to understand which legislation social media should comply with.

Faced with the uncertain role of platforms, cancel culture has a particular aim: to pursue social justice. This justice is enforced through shaming. Anyone found guilty of not complying to the standards, is bound to be shamed. The act of shaming has always existed, but has gained a great deal of momentum through social media. Some authors believe shaming is a characteristic of the technologically empowered yet politically precarious digital citizen (Ingraham and Reeves, 2016). Ineffective politics pushes users to react, transforming shaming culture into meaningful political participation. According to Ingraham and Reeves, publicly shaming others distracts us from a larger crisis we seem to have little control over. It also allows us to perform agency on an obtainable smaller digital scale. Cancel culture, and other movements of vigilantism, point to one person to make an example of them. Holding someone accountable can be done in private, but cancel culture turns it into a public example of moral standards.

The R. Kelly case is an excellent example of how cancel culture evolves. R. Kelly is a famous musician, recently arrested for multiple sex crimes. Over 20 years, the number of allegations continued to grow but without any court conviction. His prominent presence on online platforms was seen as a systematic disregard for the well-being of black women, his primary victims. Cancel culture supports the idea of first believing the victims, a concept also promoted by the #MeToo movement. In this way, the need for justice started a social media boycott under the name #MuteRKelly. Users felt he shouldn’t be featuring in music streaming platforms, or continuing his career in general. The website muterkelly.org explains the reasons for the boycott:

By playing him on the radio, R. Kelly stays in our collective consciousness. [...] That gets him a paycheck. That paycheck goes to lawyers to fight court cases and pay off victims. Without the money, he’s not able to continue to hide from the justice that awaits him. It’s not an innocent thing to listen to him on [sic] the car to work. That’s what helps continue his serial sexual abuse against young black women. That makes us all an accomplice to his crimes. (#MuteRKelly, 2018)

People were encouraged to boycott him by sharing #MuteRKelly on all platforms, to report or perform similar actions on music streaming services, and to post on the topic as much as one could. At this time, Spotify removed R. Kelly from the auto-generated playlists and introduced the button don’t play this artist across the platform. Some users were calling it the R. Kelly button, as the moment for the release of the feature seemed connected with the boycott. Later, Spotify reversed all decisions. According to the Spotify Policy Update of June 2018, “[At Spotify] we don’t aim to play judge and jury.” The apprehension from Spotify to act adds to the discussion about the role of social media businesses: does it fall onto the users or the platforms to fight the problematic topic of hate speech? Do commercial platforms benefit from conflict?

Fig. 01 – Activist of the #MeToo movement tweeting #MuteRKelly (Burke, 2018).

Unfortunately, conflict and hate draw attention. There is a term used in the art world for such a phenomenon: succès de scandale is a French expression from the Belle Époque period (1880-1914), meaning success from scandal. The expression was applied, for example, to the 1911 Paul Chabas painting Matinée de septembre portraying a nude woman in a lake. The nudity of the piece caused controversy, and several complaints culminated in a court case against the public exhibition of the painting. The discussion was dramatic. The Paris City Council passed ordinances prohibiting nude paintings; meanwhile, gallery owners were purposely placing copies of Chabas’ work in their windows. This increased the public’s interest in the controversial painting. The example of the growing popularity of this painting shows how hate and nudity both generate controversy and thus spectacle. Scandals are easily monetised, and restrictions may only generate more interest in a subject, within the art world or on social media.

Fig. 02 – Matinée de septembre (Chabas, 1911).

Just as it is true for artists, some controversy can be convenient for online celebrities. The success from scandal shows how cancel culture may fail to hold someone accountable through shaming. R. Kelly eventually went to prison, but many other celebrities enjoyed the status of the victim. This is bound to happen as engagement comes from negative or positive reviews, dislikes or likes. Social media rewards attention, even if this attention comes from absolute loathing. The reward is apparent when views from haters on a YouTube video generate revenue for the creator. It’s cold-blooded, but hate can bring the creator profit. Furthermore, in the way social media systems function, the virality of shaming also benefits the social media business model. (Trottier, 2019) The commotion generates online traffic. Luckily for the platforms, cancel culture excels in creating viral content.

Cancel culture uses techniques to spread quickly and gain visibility by finding its way to the popular topics, through hashtags, using specific location tags. The trends section of Twitter is a special place of interest. When an expression is used in abundance by the users, it gains a position of attention on the platform. On Twitter, the trends show by default, becoming a pervasive feature of the platform. The design decision to implement it this way, made the trends into a desirable arena for publishing messages. When the words #MuteRKelly were trending, they reached millions of people and spread the word to boycott the musician. The structure of Twitter, and of all the platforms we use, have intrinsic characteristics that control or promote user behaviours.

Twitter trends demonstrate how any interface feature can become dangerous. Although trends can be a news source, they also favour the mob mentality, typical in online trolling and harassment. Andrea Noel is a Mexico-based journalist who has been investigating various alarming situations behind Twitter trends. Through her work, the journalist obtained access to internal emails of a troll farm from 2012 to 2014. Troll farms are organisations that employ a vast amount of people to create conflict online, to distract or upset users. In the emails, Noel read how these people organise in order to divert online attention from important issues. One of the strategies is the fabrication of trending topics on Twitter. This falsification means that #FridayFeeling can be a topic tweeted every second by a company in Mexico to avoid #MuteRKelly to reach the trends. This shows how publishing vast amounts of noise in social media prevents other conversations from happening.

Faced with Noel’s research, I wanted to gain a better understanding of the popularity of boycotting through what’s trending on social media. For that reason, I created a bot that looks for trends in the United States related to cancel culture. The bot collects the trending topics methodically and saves them so I can interpret them later. It listens for specific words I know are correlated with cancel culture – though I may be missing other specific hashtags of which I’m not aware yet. The bot isn’t perfect, and it doesn’t need to be. Throughout the time it’s been running, it has illustrated some of the activity of users with digital vigilantism.

In my research, only in November 2019, Halsey, Lizzo, K-pop stans, Uber, Amber Liu, John Bolton’s book and the cartoon Booboo all reached the trends to be boycotted. Lizzo made sexualised comments about a group of singers, Amber Liu spoke in favour of a racist arrest in the US. Both were actions viewed as morally reprehensible, which provoked a reaction on social media. All the subtleties of these stories don’t reach my bot or the screens of billions of people. What is spread, tweeted and retweeted is the word boycott. All further details are stripped away in order to gain exposure.

Fig. 03 – Bot activity showing trending hashtags (Graça, 2019).

The first time I noticed and understood call-out culture, I was proud of watching women and immigrants like me creating a critical mass of collective action against hate. Together, and stronger in their unity, users were vocalising their concerns with hate speech and succeeding in removing accounts and comments that were harmful to these communities. Although there was still some outcry over people being too sensitive or not knowing how to take a joke, it was clear by looking at the number of people jumping on the movement that there were many users concerned with online abuse. It was essential to be more caring on social media. The movement was also an opportunity for me to learn. At the time, I wasn’t surrounded by many people from different backgrounds, and the online discussions made me realise other people’s concerns and be mindful of many different social issues.

However, since the #MuteRKelly phenomenon, cancel culture has developed into other expressions. The social platforms that are present in the daily lives of most people are focused on gathering attention. Attention comes from exaggerated actions, just like violence, harassment or SCREAMING. The frictions benefit the social media business model, but not the well-being of the users. To become mainstream, cancel culture needs to be viral. Aggressive. Definitely scandalous. To spread awareness to as many social media users as possible, cancel culture started to ignore essential details of a story, in order to escalate the situation to an unverified version that was more attractive. Just like tabloids and reality TV, people enjoy consuming reputations as entertainment. It makes sense that the popularity of sensationalism seen in magazines or on TV works as well on social media, and is so easily monetised. Slowly, my opinion on the movement started to shift.

What started as a collective moderation of content, became an excuse to be mean. Although there are groups of people committed to using cancel culture as an instrument to call out hate, it’s essential not to forget those who simply enjoy putting others down. Furthermore, this power to denounce others can also be abused by whoever is already in a position of privilege. Boycotting also discards forgiveness; it turns away possible allies for the social issues it tries to bring attention to. Cancel culture today is a relentless process, a massive confusion of harassment, shaming, fake morality, and a lot finger-pointing. The interest in pursuing justice together, to allow users to demand accountability and change on social media, is what originally fuelled cancel culture. But is it possible to do this without following the same techniques of trolls and haters, where people become targets of a mob? What is the potential to create safe social networks in platforms that reward scandals and outrageous viral comments?

Right now, I don’t believe cancel culture promotes any positive changes in online platforms. In fact, it often creates the opposite of its desired effect. A significant portion of the comments on call-out threads today show a general fatigue for fighting small issues and seeing problems in every situation. Cancel culture has fuelled the anti-feminists, the racists and the homophobes in screaming louder than ever their opinion that no one is able to say anything anymore without being shut down. Social media participation has been embroiled in discussions about freedom of speech, where fundamental rights are tested and pushed to allow offences to be included without any responsibility or accountability. A democratic principle that once supported journalists, activists or artists is now the main argument for problematic participation in social media. Fighting hate with hate has led to controversial outcomes. More than ever, finding good solutions to balance hate is a very urgent issue. Which better moderation strategies can we use? What approaches can be more patient, generous and fair?

Chapter 2: New platforms, different rules

As seen in the previous chapter, users that become digital vigilantes can denounce hateful content within social media platforms. Another strategy of moderation that is worth discussing is the development of Codes of Conduct, guidelines developed by communities to support the stronger regulation of online spaces.

Creating rules is essential. I encourage rules that make an explicit structure that is available and clear to every member, making space for participation and contribution. Most of the time, a lack of governance doesn’t exclude the presence of informal rules (Freeman, 1996). Instead, an unregulated group causes stronger or luckier users to establish their power and own rules, which prevent deliberated decisions and conscious distributions of power to happen at all. For this reason, the creation of Codes of Conduct within social media networks should be welcomed. A Code of Conduct is a document that sets expectations for users; it’s an evidence of the values of a community, making explicit which behaviours are allowed or discouraged, possibly decreasing unwanted hate. A Code of Conduct is very different from contractual Terms of Service or a User Policy. Instead, it’s a non-legal document, a community approach.

I followed the interesting public thread of discussions in the CREATE mailing list, archived from 2014. This list shares information on free and open-source creative projects. The back-and-forth of emails discusses the need for a Code of Conduct in an upcoming international meeting. One of the concerns is the proliferation of negative language in many Codes of Conduct. The group wishes to reinforce positive behaviours, instead of listing all the negative ones. A statement of what constitutes hate will indeed create a list of negative actions, but will that foreshadow a bad event? The discussion deepens. Is there a need for a Code at all? Some believe the convention is already friendly, while others feel that it is a privileged statement. One member compares the Code with an emergency exit, useful when you need it (CREATE, 2014).

This CREATE thread is proof that what is obvious for us, may not be obvious for others. The mailing list was debating a physical event – but also online, where distance, anonymity and lack of repercussions dehumanise interactions, it’s critical to be aware of the principles of our social networks. A Code of Conduct forces the group to make explicit decisions about its intentions and goals, things that the members might have never discussed. For example, a Code of Conduct that creates an anti-harassment policy should make a clear distinction about what constitutes harassment (Geek Feminism Wiki, 2017). What will be considered misconduct?

Discussing moral principles is complicated, especially between large groups of people. Nonetheless, there is at least one massive online platform that challenged its members to discuss user behaviours: the online game League of Legends. The game drives a powerful sense of sociality: the users create profiles, role-play different characters and form networks. The users have to work together in teams, and therefore the game provides chat tools for the players. League of Legends has its formal documents – it specifies Terms of Use, Privacy Policies, and support files. But the guidelines that govern the community are under the Summoner’s Code. The Summoner’s Code is a Code of Conduct that formulates the behaviours expected from the gamers. League of Legends is an intriguing case to look at because it not only implemented community rules, but it also maintained a Tribunal where the community discussed the misconducts.

When users reported a gamer for frequently breaking the Code of Conduct, the case would go to the Tribunal. For example, the reason for the report could be the explicit use of hate language. In the Tribunal, the system attributed the case at random to some users. It provided to each judge the statistics of the game where the incident happened, the chat log and the reported comments. A minimum of 20 users reviewed each case and then decided to pardon or punish the offender, or to skip the case as a whole. In the end, the most voted decision prevailed. The type of punishment, whether it was a warning, suspension or even banning, wasn’t decided by the users, but by a member of the game administration team. This system was well-accepted amongst the players: over the first year it was online, the Tribunal collected more than 47 million votes.

The League of Legends Tribunal is, in essence, a court of public opinion. In a very similar way to the actions described in the first chapter, there is a community that enjoys being vigilant of others. The Tribunal was a temporary feature, but in online forums where people reminisce about their time in the platform, many users seem to miss it. Some users reflect how proud they were for removing toxic players from the community; others remember how the Tribunal entertained them.

Fig. 04 – A League of Legends Tribunal case (Kou Y. and Nardi B., 2014).

I wanted to include the example of the League of Legends Tribunal because it illustrates the difficulties of sharing the role of moderation with a vast community. One of the problems for the developers of the game was the time the Tribunal needed to achieve a decision, especially compared to automated systems. Reading the comments and the solutions for each case on the platform allows a backstage view of the frustrations of reaching consensus. This system possibly opened the eyes of the unsuspecting user to the amount of hate circulating on the platform, and the challenges of managing a community. It also made clear that moderation needs a quick and prompt reaction to be effective – not only on commercial platforms, but also in other systems that deal with reports, so users can feel their issues are being addressed.

A single set of rules that affects one large community can feel limiting, and as seen in League of Legends, can also be hard to enforce and manage. In contrast, the idea of creating independent clusters of users in one platform, thus forking systems and guidelines, is appealing. One of the social platforms that promotes a diversity of guidelines within its community is Mastodon. Mastodon is a social media with microblogging features, similar to Twitter or Facebook. It is a community of communities, a federated and decentralised social media platform. Being decentralised entails a distribution of authority: each server can implement its own vision while sharing a common platform. A federation entails that users from different groups can socialise with each other, but everyone has their experience more tailored to their liking. Practically, while sharing the same platform, a user can be part of a group which blocks one kind of content, while another group allows it.

On the platform, the different community groups are called instances. Navigating through these reveals the different rules sanctioned by users. ComicsCamp.Club is an instance focused on art, especially on comics and narratives. As most Mastodon communities, there is a Code of Conduct that serves as a set of guidelines for user behaviours. These are informal rules moderated by the community, not legal documents. The Code of Conduct of this group reminds the members to engage in a positive or supportive manner, and only critique work when requested; it also gives advice, for example on how to proceed when a discussion becomes hostile. On 12 March 2020, I started an online conversation with Heather, one of the administrators of ComicsCamp.Club. She told me how “Codes of Conduct are definitely a common practice on Mastodon, due to the nature of many different communities and people trying to curate their own experience.” Since she first took over as administrator at the beginning of 2019, she has continued to edit the guidelines in response to the needs of the group. Indeed, a Code of Conduct is a document that should keep evolving to respond to the new challenges and values of a community.

It’s important to understand that user rules don’t follow any particular view on morality. For example, CounterSocial is another instance on the platform that blocks entire countries, such as Russia, China, Iran, Pakistan or Syria. This instance asserts that blocking countries aims to keep their community safe by not allowing nations known to use bots and trolls against “the West”. This may seem dubious behaviour, but it’s seen as entirely legitimate on Mastodon. I’m laying out these examples to highlight the diversity of approaches inside Codes of Conduct and their documentation. The community is independent to create its guidelines; they can choose who to invite and block from their network. The final question of CounterSocial’s “frequently asked questions” section says it all: “Who defines these rules, anyways?” The answer is: they do.

Fig. 05 – Rules on CounterSocial (Counter.social, 2020).

A Code of Conduct doesn’t deter all behaviours that aren’t accepted by the group. Still, in platforms that allow users to impose their rules, social media users can mitigate online hate in a much more direct way. Just like in cancel culture, community rules prosecute bad behaviours inside the community. However, in a very different approach from cancel culture, the repercussions of not following the conduct are predominantly dealt with in private. The moderators make use of warnings, blocking, banning. While some groups have zero-tolerance policies, others employ more forgiving proposals – “If the warning is unheeded, the user will be temporarily banned for one day in order to cool off.” (Rust Programming Language, 2015).

An online conversation with the administrator and moderator of the Mastodon instance QOTO brought to light how the bottom-up initiative of moderating hate is a co-operative task. QOTO is one of Mastodon’s oldest instances, created for scholars in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and others. It has, at the moment of writing this text, 12,322 users. As with most Mastodon communities, there are some rules to follow. I wanted to know why they had rules, how they were created, and how they are now enforced. Jeffrey explained how all rules are discussed with the community first, after which the moderators ultimately vote on decisions. They like everyone’s voice to be heard, so besides discussing their rules within the community, they also discuss them with administrators of other instances who may have a relevant opinion (Graça 2020, personal communication, 12 March).

It’s not only marginalised communities that are enjoying more controlled networks, guided with different rules than mainstream social media. The idea of building safe spaces where users can be active participants and moderators of their social networks is proactive and resonates with a lot of people. However, safe spaces open the doors for fascists to make their own protected networks as well. This is the case of Gab, a social platform that advocates for free speech with no restrictions. Its terms of use don’t ban bullying, hate, racism, tormenting or harassment. The only point that briefly mentions any liability is when engaging in actions that may be perceived as leading to physical harm or offline harassment. For a long time, the platform’s logo resembled Pepe the Frog, an image appropriated by the alt-right. As expected, Gab is known for hosting a lot of hateful content.

In 2019, Gab forked off from Mastodon into a custom platform. The migration was an attempt to dodge the boycott it was facing. Apple Store and Google Play had removed Gab’s mobile app from their services earlier. Although many Mastodon communities already have their own rules against racism and can block users or communities that don’t, Gab still benefits from the platform system as a whole. There was a great deal of controversy regarding whether Mastodon should ban Gab’s instance, as a general platform policy. In this case, the platform as a company felt pressure to intervene beyond community-driven rules. For the founder of Mastodon, the only possible outcome was allowing Gab to use and fork the open-source platform. This situation upset some users. The perceived inadequate response to the alt-right from Mastodon was one of the reasons for the creation of more alternative platforms.

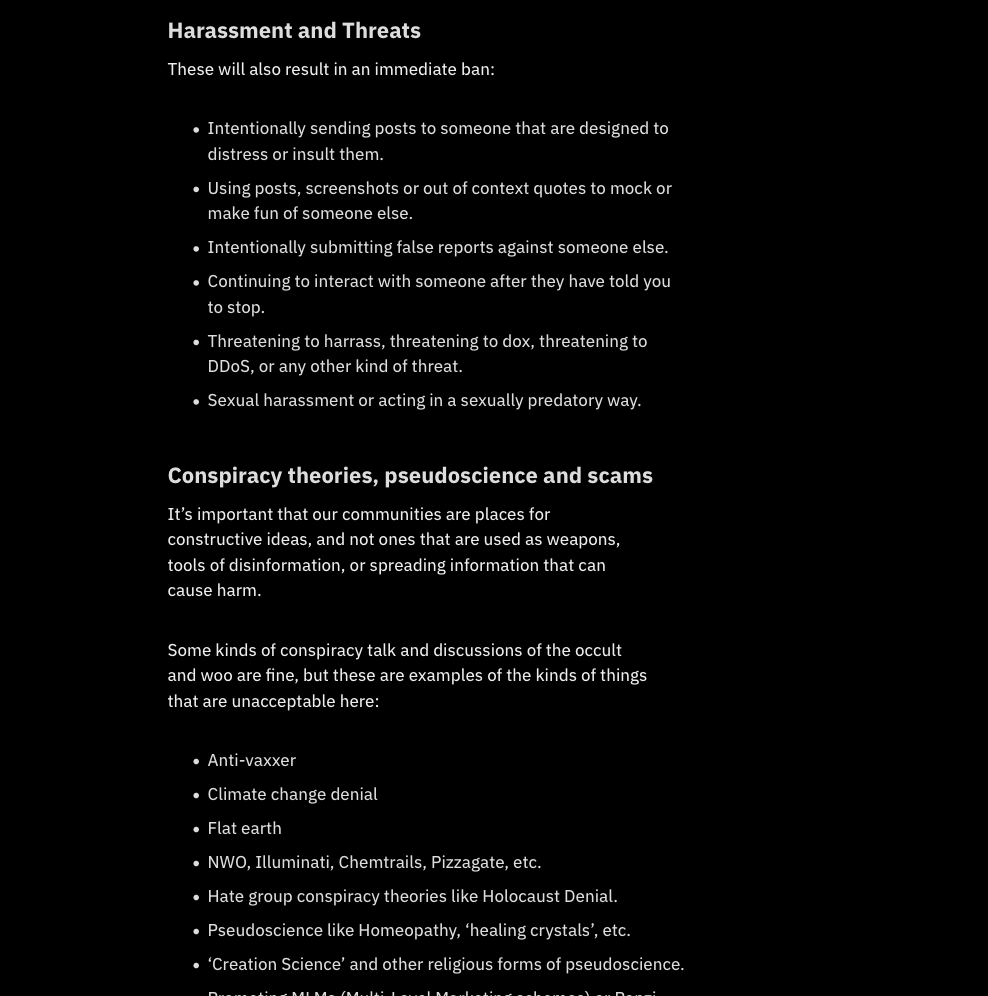

One of these platforms is Parastat, a new social media under development that aims to contribute to a more humane society. Parastat’s moderation policies are comprehensive. Parastat promises an immediate ban for hate speech, threats or harassment. Beyond the norm of other platforms, it also doesn’t allow flirting, conspiracy theories, anti-vaxxers, homoeopathy, healing crystals, and many other topics. In the present online environment where hate proliferates, there are enough reasons to build safe spaces – online networks where people come together, can express themselves and feel protected from outside abuses. However, with a Code of Conduct as rigorous as Parastat’s, I wonder if there will be less bickering and problems? Is it possible to only allow constructive ideas into a social network? When does a Code of Conduct stop providing boundaries and instead start creating thick walls that alienate users?

What is interesting to me in community guidelines is how evident the network becomes: the values, the members, the ideas that connect people, the purpose of having a group. A Code of Conduct is becoming increasingly common in different kinds of networks, sometimes prompted by social pressures or as a requirement to seek financial support. It’s important to note that a Code of Conduct doesn’t only set rules but also needs people actively involved with the community, to manage reports and possible malpractices. It also needs visibility and a plan for distribution. Only this way can a Code of Conduct evolve from a written document into a tool that actually helps reduce hate or any unwelcoming behaviours. Community rules are not only documents, but labour-intensive routines that imply human effort and involve the community. These documents became relevant to me when I understood the logic behind them.

Fig. 06 – Parastat’s Code of Conduct (Parastat, 2020).

The emergence of Codes of Conduct on social media provides more agency to users, as they can choose how and what is shared in their networks. Small platforms seem more welcoming of these documents and more capable to regulate online hate. This is probably because it’s easier to share similar ideals with fewer users, but also because mainstream commercial platforms have different preoccupations, such as making a profit. Nonetheless, should mainstream platforms with massive amounts of users have stronger guidelines? Is it possible to manage billions of different-minded people with one set of rules? How can moderators enforce regulations on a large scale? Big platforms still have a long way to go in the way they manage hate, but I believe one crucial step is to work on their policies – to be straightforward on what constitutes hateful actions and how they won’t be tolerated. It’s essential to find ways to cater to diversity within their guidelines, not forgetting the problems that target specific groups. Which tools can support users’ different needs? How do we design for diversity?

Chapter 3: Designing change

Throughout this text, I analysed the popularity of vigilantism and the development of Codes of Conduct. While both of these approaches use human interventions to control hate, there is a plethora of compelling software tools that have the same goal. Users build tools outside the formal development of social-media businesses to moderate content on their own terms. Together, the community shares notions of morality and customises its platforms, gaining more control over the way users participate in their networks. The interface is a crucial component of social media in dealing with online behaviours. The design shows the actions we can do, and what and how we see content on the platform. Add-ons, plugins, and other tools can be very efficient in avoiding hate when the platform tweaks, removes or adds to the design of the interface. In this way, it’s necessary to begin this chapter with an understanding of the importance of interface design.

In 1990, Don Norman wrote that “the computer of the future should be invisible”, meaning that the user would focus on the task they want to do instead of focusing on the machine (Norman, 1990). Much like a door, you go through it to go somewhere else. But the designer and researcher Brenda Laurel reminds us that closed or opened doors allow different degrees of agency. A door that opens for you, a small door for children, a blocked door: the interface defines the user role and establishes who is in control. What the platform allows the user to do, the possibilities for a person on social media to write, post, and reach others, are affordances of the platform. The term affordance, as Norman has interpreted it, is now a buzzword in the field of design.

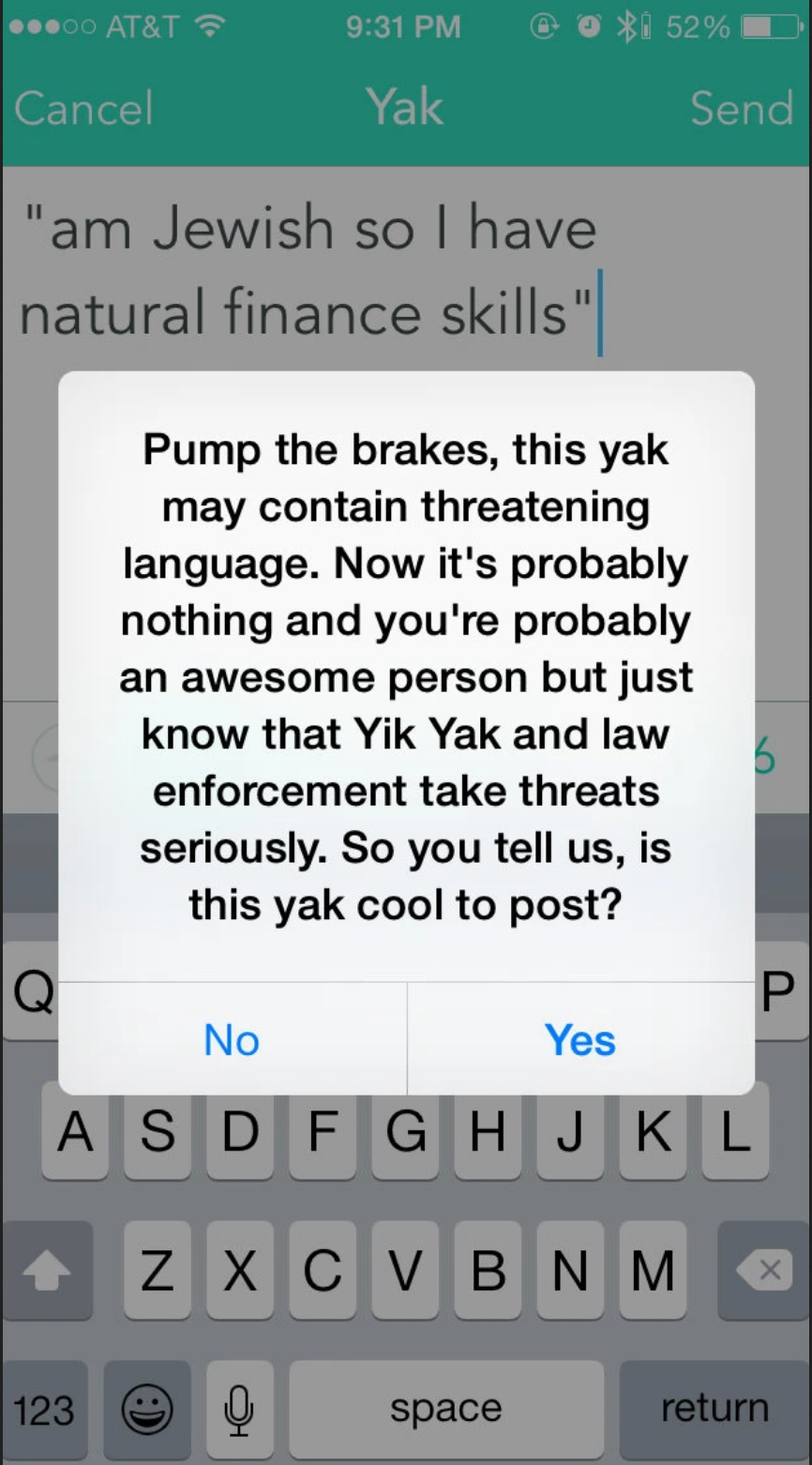

If platforms have intrinsic characteristics that guide user behaviours, social platforms become partly responsible for the way users share hate, mainly if these platforms facilitate or even perform abusive actions. To understand how platforms can accommodate hate, it’s valuable to look at Yik Yak, a former social media app targeted at college students. The platform allowed users to post messages to a message board, in anonymity. The privacy policy of Yik Yak did not approve the identification of the users without specific legal action. The app bounded a small community, as the user would only see the posts of people around them. Yik Yak was anonymous and local. It was also community-monitored. Users upvoted or downvoted posts on the message board, and as a result, the upvoted messages would become more visible on the interface. The app was launched in 2013, and at one point in 2014, Yik Yak’s value reached 400 million dollars. Only three years later, however, the developers published a farewell note, and the app shut down.

One day in college, student Jordan Seman saw a horrible message about her and her body on Yik Yak. The hyper-localisation of the app meant that whoever “yaked” the insults was someone extremely close to her. Seman then wrote an open letter to her school and peers, where I found her story. The letter was published for the Middlebury College community, but it definitely resonated within other groups using the app. The features of the platform could allow for a close self-regulated community, and anonymity could mean safety for some people. Instead, the same characteristics tolerated the spread of hate on college campuses without any accountability. The message board was a burn book: a place to vent, to make jokes about others, to bully. In the case of Yik Yak, the platform design facilitated the shaming of Jordan. She asks in her open letter: “Is this what we want our social media use to be capable of?” (Seman, 2014)

Yik Yak’s structure is very similar to that of Reddit. Yik Yak also maintained message boards, allowed pseudonyms, and maintained a “karma” system. Identical design choices on Reddit, its algorithm and its platform politics, have been analysed and alleged to support anti-feminist and misogynistic activity (Massanari, 2017). It’s clear that the affordances of platforms deeply shape user behaviours. In this way, it’s not surprising that while Yik Yak developers were dealing with hate on their platform, the same was happening on Reddit. In August 2014, a controversy around the gaming industry culture instigated coordinated attacks, mainly targeted at women. The movement spread and escalated with the usage of the hashtag Gamergate on Twitter. The repercussions of such actions were hateful. The #gamergate harassment included doxing (publishing sensitive personal information), intimidations, swatting (fraudulently mobilising heavily armed police against the victim), death threats, bomb alerts, and shooting warnings.

Fig. 07 – Yik Yak attempts to reduce harassment on the app (Mahler, 2015).

The stories of Yik Yak and Reddit exemplify how the interface can act as an agitator. For this reason, technical tools to reduce hate through the interface become meaningful and required. One feature that allows shutting down harassment is to stop listening to the source by blocking the user. However, there are some situations where individual blocking is not enough.

As a result of the Gamergate controversy, Charles Hutchins created Block All Twerps, a blocklist for Twitter. Block All Twerps programmatically collects and blocks users that are harassing, following or retweeting harassment (Hutchins, 2016). When a user subscribes to a blocklist, their feed will ignore the presence of any people added to the list – no tweets, notifications, messages. In a broad sense, if a user subscribes to Block All Twerps, they will stop seeing content from potential harassers. The idea of who should be blocked derives from Hutchins’ ideals. The mass blocking may also reproduce discriminating views of the developer, and the creator of this work is well aware of it.

Block All Twerps is not the first blocklist on Twitter. Before Gamergate, feminists were already using mass blocking strategies. The first shared blocklist was The Block Bot which maintained a list with three levels of strictness – level 1 for users who posted hateful content, to level 3 for microaggressions. Shared blocklists like this one are developed and supported by the community. They are bottom-up strategies to individually and collectively moderate Twitter experiences (Geiger, 2016). A community co-operates a list, deciding on who is listened to or silenced. The blocklists follow shared views of morality, ruling themselves by what each member feels is harassment, hate speech, or any target the list has. Some of the tasks of the members of the group include adding more people to the list, removing some, explaining the reasons for the block, providing tech support, and dealing with complaints. This way, the practice of preserving a blocklist happens through an informal structure, creating a network of care.

Blocklists use a different approach to cancel culture to reduce hate. Blocklists don’t aim to remove problematic users from online spaces, but choose instead to not engage with them. Users who use block bots are not escalating a discussion but trying to stay away from it. I understand and encourage users who respond directly to haters and hate speech. Nonetheless, I believe it’s equally important to create spaces where users don’t need to fight those battles, where users don’t have to respond to harmful behaviours while they engage with their networks. I don’t like to participate in online discussions, so the benefit that I see in software tools is that they produce generally quiet actions. With blocklists, a person may not even detect they were blocked. However, if they do, some lists give the possibility to ask for an explanation and possibly get unblocked.

For example, the group behind The Block Bot provides an email address to forward complaints. Although there’s a word of advice – “... make peace with the possibility that some people on Twitter may not wish to talk to you and that’s okay.” (The Block Bot, 2016). Different people manage the list, so who is or isn’t blocked doesn’t reflect strict guidelines. In the process of adding someone to a blocklist, it is common to add the reason for such blocking. On the one hand, the explanation adds disclosure for users. On the other hand, it shames users and their behaviours.

Software approaches reshape the way users interact with social platforms. Voluntary developers create blocklists because of the lack of a comparable feature on the platform. Even before block bots, Twitter users helped each other identify people to block by posting the hostile user’s ID on the public timeline. In 2015, Twitter CEO Dick Costolo would write in a leaked internal memo: “We suck at dealing with abuse and trolls on the platform and we’ve sucked at it for years.” (Independent, 2015). That same year, Twitter added the feature to share blocklists into their source code. Today, sharing who is blocked is not available anymore, so blocklists continue as parallel activities. Nonetheless, since 2015 much more attention has been given to moderation on social media. Besides the platforms researching and trying new approaches, a growing number of plugins, extensions and bots are created every day.

While experimenting with some software tools, I understood how they instantly reduce the flow of some topics or users. They also suggest greater changes for social media platforms; it’s not uncommon for grassroots tools to turn into real features. For example, on Twitter, flagging started as a petition from 120,000 users who wanted more report mechanisms to deal with online abuse (Crawford and Gillespie, 2014).

Flagging takes the expression of the nautical red flag, meaning danger, a warning; and, on social media, a report of something improper. It’s a method for users to show discontent towards something or someone. On some platforms, the action of flagging is binary – the user is either against the content or not. In others, flagging is more thorough. For example, YouTube asks for the user to choose from nine options describing why the video violates community guidelines. Flagging can allow for removing hateful content, mainly when used as a collective tool. As the outcomes of individual flagging are often undisclosed, it is frequent that a community organises and demands change by using the tool in cooperation with others. A call to action is posted online for people to use the report button against some post or user. This amount of feedback will put pressure on the platforms to act – to remove someone from the network, for example.

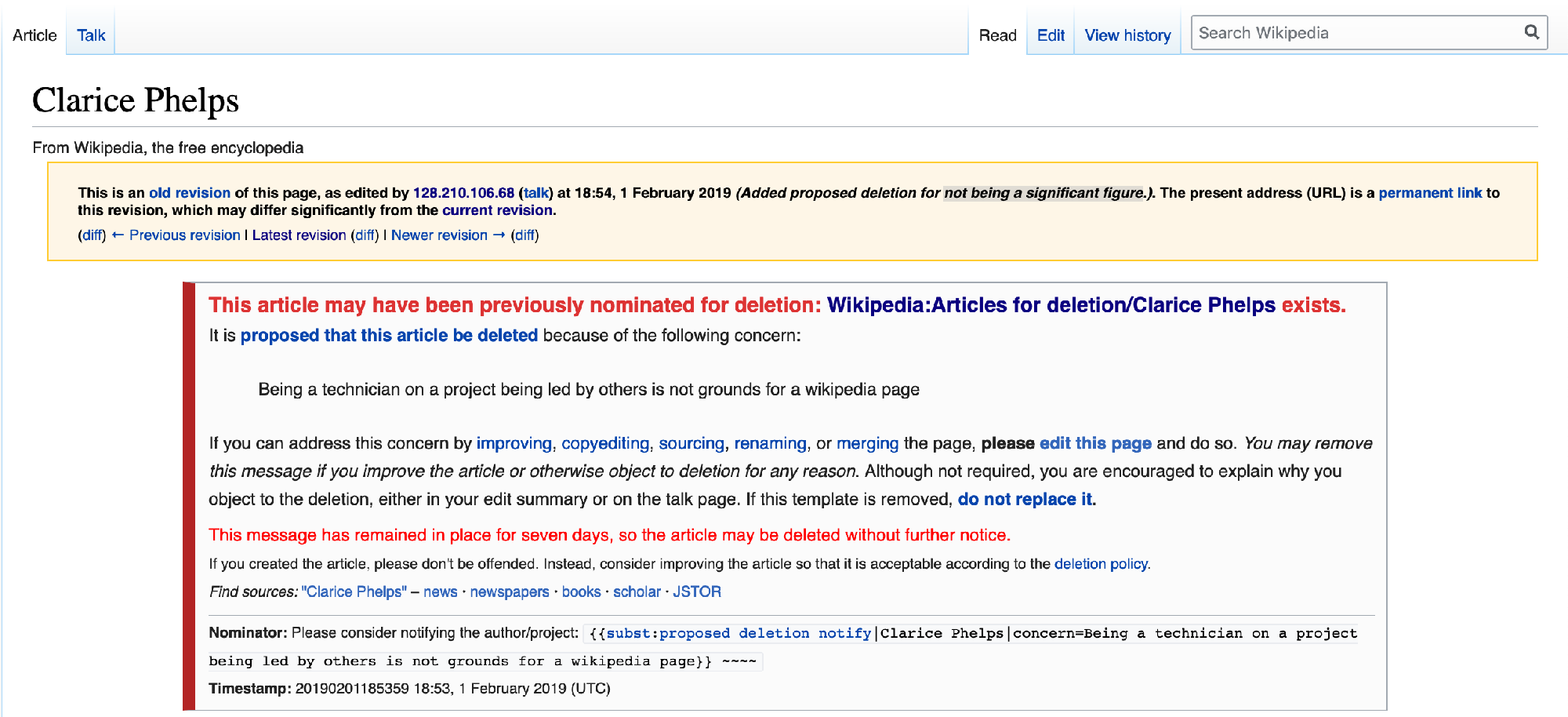

Flagging is a feature on many social platforms, and a tool to moderate content. However, users can use it to report all kinds of things, including genuinely valid material. Different users of social media can use flagging in varied ways, which explains how tools are just a means to do something. They don’t obey single handling but rely heavily on the user. An unfortunate example of flagging is the report of biographies of females on community platforms such as Wikipedia. Last year, the flagging and subsequent removal of pages about women generated a great deal of commotion and media coverage. Wikipedia members used the flagging system to ask for the removal of pages of several women, on a platform that already lacks sufficient female contribution and exposure. As of February 2020, only 18.3% of biographies in the English Wikipedia are about women (Denelezh, 2020).

Fig. 08 – One of the Wikipedia biographies that generated the most media coverage. The page was deleted twice, protected against creation, considered in three deletion reviews, one Arbitration case, and overall intense discussion about meeting a notability standard (Wikipedia, 2020).

Besides flagging, Wikipedia is interesting to analyse for its other software tools. Without assigned moderators, the task of editing content in Wikipedia articles is the result of public collaborative discussion between users. As anti-hate measures, the editors get help from tools such as ClueBot NG, ORES or the AbuseFilter extension. These software tools detect and remove hateful content. The tools are always evolving into more sophisticated forms, for example through the implementation of machine learning. The automatisation of moderation is becoming a common practice on social media. But so far, the intricate nature of hate and its context, still require extensive human action. Until someone comes up with better social solutions, technical tools can help users to deflect hateful content.

In this chapter, I have discussed the possibility of creating tools in the margins, as complements or plugins, as is the case of blocklists. Also relevant is the manipulation of some already integrated features, such as flagging. The openness of forums also makes them a great place to discuss which tools are needed. The technical tools referred to in this text are used within coordinated strategies to help shape social spaces. They are generous approaches to filter out hate from the networks of users. The tools, when used collectively, help users share software knowledge, design skills and media know-how. This cooperation is especially helpful for users without the resources to implement adjustments that can make a difference in their experiences with social media. The community that shares its knowledge, and is active in removing hate within and outside the community, creates important support systems – networks of care.

Conclusion

Online hate has existed ever since people could share messages on computers. In 1984, a bulletin board system called Aryan Nations Liberty Net was carrying racist material, years before internet use became widespread. Two decades later, the participatory “web 2.0” foreshadowed a cultural revolution. The potential for social media to connect people grew, as well as the ability to spread nasty comments, to harass someone, to make threats. To say that online spaces are filled with hate is nothing new, and common knowledge at this point. However, the ways of dealing with hate continue to increase and improve, always trying to stay as progressive as possible, aiming to catch up with the most recent hurdles. Discussions about moderating social platforms are challenging issues that are making headlines right now.

Throughout this text, I pinpointed several of the multiplicity of efforts to reduce hateful content from the perspective of users. These users, fed up with encountering harmful behaviour online, started coming up with ways of protecting and maintaining their own networks. Valuable clusters of people organise on the margins to make social media spaces more enjoyable. The communities that grow within these actions build networks of care. I suggest that these bottom-up strategies are essential to imagine and create better social networks. Official responses from the platforms are necessary, but I propose that informal community movements are crucial to managing social platforms and that they deserve more attention, debate and recognition.

The point where it gets more complicated is the question of where to embrace bottom-up strategies such as Codes of Conduct, and where these guidelines constrain discussions. Parastat’s strict rules, mentioned in the second chapter, may limit questions and relevant dialogues on a wide range of topics. Another problem with some approaches, such as cancel culture, is that they assume moral righteousness, where one’s morality becomes superior to that of others, and therefore more important, more worthy of spreading through media. Finally, there’s a concern that online moderation may reduce freedom of speech. Restricting freedom of expression can be very dangerous, and can lead to a corruption of democratic values. For example, governments shutting down internet access in times of conflict are removing spaces to express opinions and share news.

Freedom of speech is an essential right, with duties and responsibilities, but also exceptions. Philosopher Karl Popper’s Paradox of Tolerance clarifies the impossibility of allowing everything and being completely tolerant. Popper explained how it’s essential to set boundaries in order to create a truly tolerant society. I believe the same applies to social media platforms. In Popper’s words: “We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant.” (Popper, 1945). This can be done by providing more strategies to limit abusive content from and toward users: better report systems, blocking tools and community guidelines. In this text, I have analysed these approaches to reduce hate content online. Still, I couldn’t mention all possibilities – manifestos, protests, low tech devices, memes – these are all appropriate strategies.

While writing this thesis, I was, at times, feeling defeated. At the beginning of my research, I was trying to place the blame for online hate on the interface, on the gatekeepers of platforms, even on capitalism itself if it seemed feasible. All these forces have a massive influence on online behaviours. However, as users, it’s hard to change these forces. For this reason, my work sheds light upon those user actions and intricate communities that work against online hate. These networks of care share ideas and mindsets of what should be acceptable, and work as voluntary collectives to cut down hateful behaviours from their social spaces. Even if the outcomes are dubious at times, these are very generous approaches to moderate social media. There’s now a clear answer to the question that kept surfacing in my mind – is it possible to fight online hate? The answer is: absolutely.

References

-

Bromwich, J. E. (2018) Everyone Is Canceled. The New York Times, 28 June. Available at: https://www. nytimes.com/2018/06/28/style/is-it-canceled.html (Accessed: 9 February 2020).

-

Communications Decency Act 1996, section 230. Available at: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/47/230 (Accessed: 5 January 2020).

-

Crawford, K., & Gillespie, T. (2016) What Is a Flag For? Social Media Reporting Tools and the Vocabulary of Complaint. New Media & Society, 18 (3): 410-428.

-

Denelezh (2020) Gender Gap in Wikimedia projects. Available at: https://www.denelezh.org/ (Accessed: 28 February 2020).

-

Facebook, Inc. (2020) Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2019 Results. Available at: https://investor.fb.com/investor-news/press-release-details/2020/Facebook-Reports-Fourth-Quarter-and-Full-Year-2019-Results/default.aspx (Accessed: 2 March 2020).

-

Freeman, J. (2013) The Tyranny of Structurelessness. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 41 (3-4): 231-246.

-

Geek Feminism Wiki (2014) Community anti-harassment/Policy. Available at: https://geekfeminism.wikia.org/wiki/Community_anti-harassment/Policy (Accessed: 9 March 2020).

-

Geiger, R. S. (2016) Bot-Based Collective Blocklists in Twitter: The Counterpublic Moderation of Harassment in a Networked Public Space. Information, Communication & Society, 19 (6): 787-803.

-

Hutchins, C. (2016) @BlockAllTwerps. Art Meets Radical Openness (#AMRO16). Available at: https://publications.servus.at/2016-AMRO16/videos-lectures/day2_charles640lq.mp4 (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

-

Ingraham, C. and Reeves, J. (2016) New Media, New Panics. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 33 (5):455-467.

-

Rust Programming Language (2015) Our Code of Conduct (please read). Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/rust/comments/2rvrzx/our_code_of_conduct_please_read/ (Accessed: 9 February 2020).

-

Massanari, A. (2017) #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s Algorithm, Governance, and Culture Support Toxic Technocultures. New Media & Society, 19 (3): 329-346.

-

MuteRKelly (2018) Why Mute R. Kelly? Available at: https://www.muterkelly.org/about (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

-

Norman, D. (1990) Why Interfaces Don’t Work. The Art of Human-Computer Interface design. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/2849717/Why_interfaces_don_t_work (Accessed: 9 February 2020).

-

Popper, K. R. (1945) The Open Society and Its Enemies. London: Routledge.

-

Seman, J. (2014) A Letter on Yik Yak Harassment. The Middlebury Campus. Available at: https://middleburycampus.com/27709/opinion/a-letter-on-yik-yak-harassment/ (Accessed: 9 February 2020).

-

Sherwin, A. (2015) Twitter CEO: “We suck at dealing with abuse and trolls”. The Independent, 5 February. Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/news/twitter-ceo-dick-costolo-we-suck-atdealing-with-abuse-and-trolls-10026395.html (Accessed: 4 February 2020).

-

Shullenberger, G. (2016) The Scapegoating Machine. The New Inquiry. Available at: https://thenewinquiry.com/the-scapegoating-machine/ (Accessed: 2 March 2020).

-

Silva, Mondal, Correa, et al. (2016) Analyzing the Targets of Hate in Online Social Media. International AAAIConference on Web and Social Media. Available at: https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM16/paper/view/13147/12829 (Accessed: 3 February 2020).

-

Spotify (2018) Spotify Policy Update. Available at: https://newsroom.spotify.com/2018-06-01/spotify-policy-update/ (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

-

The Block Bot (2016) Introduction to @TheBlockBot. Available at: http://archive.is/WJ19U (Accessed: 8 March 2020).

-

Trottier, D. (2019) Denunciation and Doxing: Towards a Conceptual Model of Digital Vigilantism. Global Crime, pp. 1–17.

Images

-

Fig. 01. Burke, T. (2018) Activist and founder of the #MeToo movement tweeting #MuteRKelly. [Screenshot by author] Available at: https://twitter.com/TaranaBurke/status/994602647041822720 (Accessed: 28 April 2020)

-

Fig. 02. Chabas, P. (1911) Matinée de septembre [Oil on canvas]. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/488977 (Accessed: 28 April 2020)

-

Fig. 03. Graça, R. (2019) Bot activity. [Screenshot by author] Available at: https://twitter.com/CancelledWho (Accessed: 28 April 2020)

-

Fig. 04. Kou Y., Nardi B. (2014) A Tribunal Case. [Screen capture] Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/35a3/414db2e79988a014aa1fb80b8196020ea02b.pdf (Accessed: 28 April 2020)

-

Fig. 05. Counter.social (2020) Community rules. [Screenshot by author] Available at: https://counter.social/about (Accessed: 28 April 2020)

-

Fig. 06. Parastat (2020) Code of Conduct. [Screenshot by author] Available at: https://parast.at/coc/(Accessed: 28 April 2020)

-

Fig. 07. Mahler, J. (2015) “Who Spewed That Abuse? Anonymous Yik Yak App Isn’t Telling” The New York Times. [Screen capture] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/09/technology/popular-yik-yak-app-confers-anonymity-and-delivers-abuse.html (Accessed: 28 April 2020)

-

Fig. 08. Wikipedia (2020) Clarice Phelps. [Screenshot by author] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clarice_Phelps (Accessed: 28 April 2020)